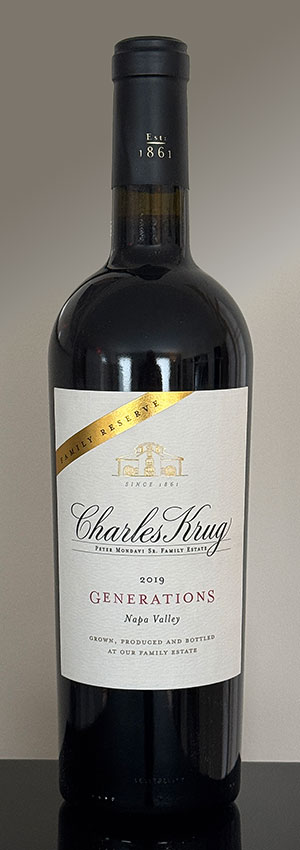

Charles Krug Generations

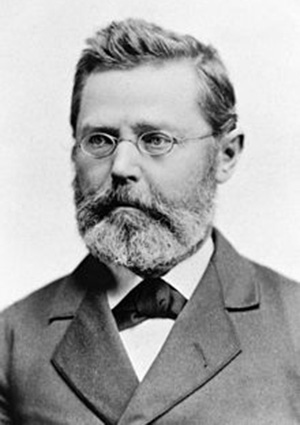

Starting in 1861 in St. Helena, Prussian-born immigrant Charles Krug began transforming 540 acres of prime Napa Valley land that had come to him through his marriage to Carolina Balein. His efforts culminated in what is widely recognized as Napa Valley’s first commercial winery. In 1882, he opened his tasting room, another Napa first.

Krug arrived in California during the Gold Rush era, and soon shifted his attention from prospecting to viticulture, building the stone winery that would become a cornerstone of Napa’s agricultural identity. From the beginning, Krug’s operation was notable for its ambition and for bringing structure and scale to what had been a largely experimental local industry.

The winery’s early success was influenced by both Krug’s business instincts and the valley’s growing reputation as a place where European grape varieties could thrive. But like many historic California wineries, Charles Krug faced major challenges in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including vineyard diseases (especially phylloxera) and shifting market conditions. The greatest blow to the American wine trade came with Prohibition (1920–1933), when most wineries were forced to shut down or survive by producing sacramental wine or grape products. Charles Krug endured through these years, but the broader Napa Valley wine economy stalled for decades.

A defining new chapter began in 1943, when the winery was purchased by Cesare and Rosa Mondavi, Italian immigrants who had already built a successful grape and wine business in California. Their acquisition of Charles Krug marked one of the most important transitions in Napa’s post-Prohibition recovery. Under the Mondavi family’s stewardship, the winery modernized, expanded vineyard sourcing, and reestablished itself as a serious producer at a time when Napa was still rebuilding its reputation. One innovation was the first use of imported French oak barrels as part of the aging system.

The Krug estate soon became the centerpiece holding of a family that would become synonymous with Napa Valley’s rise on the world wine stage.

Today, Charles Krug remains family-owned, with Peter Mondavi Sr. (1914–2016) long credited for guiding the winery through decades of growth and reinvention, and later generations continuing that legacy. The estate is known for combining historical continuity with practical innovation—preserving its landmark stone buildings and heritage while adopting modern vineyard and cellar techniques. Over time, Charles Krug has become especially associated with Cabernet Sauvignon and Napa Valley red blends, reflecting the valley’s shift toward premium varietal wines in the second half of the 20th century.

The winery has also earned a reputation as a welcoming destination in St. Helena, featuring a historic Redwood grove, tastings, and food-focused events that reflect the Mondavi family’s long belief that wine belongs at the table. More than 160 years after its founding, Charles Krug stands as a living piece of Napa Valley history.

Charles Krug Generations 2019

Note: This selection is guilty of Bloated Bottle Syndrome, which I’m calling out for bottles that weigh more than the wine they contain. The web site of nearly every winery will usually include a mention of the operation’s dedication to “sustainability” and “stewardship.” Unfortunately, this often seems only to extend to the property itself. Many “premium” wines like this one come in heavier bottles to allegedly denote quality. This one weighs in at 895 grams. (As an example of a more typical bottle, Estancia Cabernet’s comes in at 494 grams.) That’s a lot of extra weight to be shipping around the country (or the world.) Even sparkling wine bottles are less than the weight of this one, and those are made to withstand high internal pressure. Unfortunately, this sort of “bottle-weight marketing” is becoming more common, especially at higher price points. But there are other ways to denote quality without weight: unusual label designs, foils, wax dipping, etc.

Plastic bottles have a lower environmental impact than glass, 20% to 40% less, in fact. And, bag-in-box packages are even less than plastic bottles. (Unfortunately, current bag technology will only keep unopened wine fresh for about a year, so they are only suitable for wines to be consumed upon release from the winery; that’s about 90% of all wine sold though.)

The carbon footprint of global winemaking and global wine consumption is nothing to scoff at, amounting to hundreds of thousands of tons per year. The latter, which requires cases of wine be shipped around the world, imprints a deep carbon footprint. Because wine is so region-specific, and only so many regions can create drinkable bottles, ground and air transportation is responsible for nearly all of the wine industry’s greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Sustainable Wine Roundtable, a group of wineries, retailers, and other companies connected to the wine industry, one-third to one-half of that total is due to the glass bottles themselves.

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/