Click here for tasting notes.

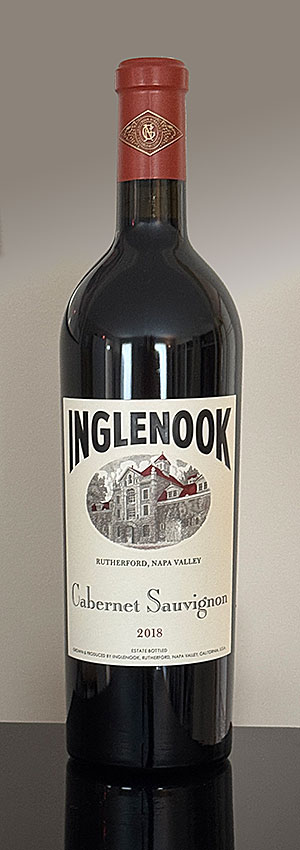

Inglenook Cabernet Sauvignon 2018

Inglenook was founded in 1879 by Finnish sea captain Gustave Niebaum. By 1887, he had amassed a total of 1100 contiguous acres, marking the inception of the Inglenook legacy. After his death and during the scourge of Prohibition the winery was shuttered. After repeal, Niebaum’s widow, Suzanne, reopened Inglenook and brought in viticulturist and enologist John Daniel Jr., Niebaum’s great-nephew, to upgrade the winemaking system.

Daniel was an uncompromising perfectionist. Under his stewardship from the 1930s to the early 1960s, Inglenook produced some of the most celebrated Cabernets in California. Daniel’s partnership with winemaker George Deuer resulted in wines that were rich, complex, and impeccably balanced, marking a period of extraordinary achievement for Inglenook. Despite the challenges of the era, Daniel was committed to producing only the best. He was one of the few vintners of his time willing to reject wines that did not meet his exacting standards, a rare and costly approach in an industry where every bottle counted.

The addition of the Napanook Vineyard in 1946 helped elevate the winery’s offerings even further, as Daniel blended grapes from this esteemed site into his best wines.

But after the sale of Inglenook in 1964, the winery’s fortunes changed. Faced with financial struggles and a declining market for premium wines, Daniel was forced to sell the winery to United Vintners for $1.2 million. Despite initial promises to maintain the winery’s legacy, the new owners quickly shifted focus toward mass-market production. Inglenook became synonymous with jug wines, and the once-great brand began to lose its luster.

But after the sale of Inglenook in 1964, the winery’s fortunes changed. Faced with financial struggles and a declining market for premium wines, Daniel was forced to sell the winery to United Vintners for $1.2 million. Despite initial promises to maintain the winery’s legacy, the new owners quickly shifted focus toward mass-market production. Inglenook became synonymous with jug wines, and the once-great brand began to lose its luster.

In the years that followed, several attempts were made to revive the Inglenook name, but none succeeded. Even a brief period in the 1980s, when quality improved under the leadership of Dennis Fife, couldn’t undo the damage caused by the brand’s association with inexpensive jug wines. By the late 1970s, Inglenook was known more for its mass-produced wines than for the exceptional Cabernets of the Daniel era.

But the story of Inglenook didn’t end there. In 1975, filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola acquired a portion of the original Inglenook estate. Coppola spent decades striving to rebuild the estate, finally realizing his dream in 1995 when he acquired the final missing piece, reuniting it with the vineyards and homes associated with Daniel. Coppola, who had long admired the legacy of Inglenook, sought to restore the winery to its former glory. Today, the Inglenook estate is a testament to the vision of both Daniel and Coppola. The iconic stone chateau, once the heart of winemaking at Inglenook, now serves as a visitors’ center and retail shop, housing artifacts from Inglenook’s history and memorabilia from Coppola’s film career.

Though the winery no longer produces wine in the same way it did during Daniel’s tenure, Coppola has worked hard to preserve and honor the legacy of Inglenook. His efforts to restore the estate and vineyards have been successful, and Inglenook now produces wines that reflect both the history of the winery and the modern standards of winemaking.

Inglenook Cabernet Sauvignon 2018

Inglenook Cabernet Sauvignon is a tribute to winemaker John Daniel Jr., who produced the much-heralded Inglenook 1941 Cabernet Sauvignon from vine cuttings brought to the property from Bordeaux by original founder Gustave Niebaum.

First known as the ‘Cask’ Cabernet Sauvignon, this wine was originally crafted in 1995 (released in 1998) to commemorate the reunification of the Inglenook property. It is now simply referred to as Rutherford Cabernet Sauvignon.

A blend of 95% Cabernet Sauvignon, 3.5% Cabernet Franc, 1% Merlot, and 0.5% Petit Verdot, this wine is a deep transparent purple in the glass. It opens with rich aromatics of dark fruit, especially blackberry, and leather. These continue on the full-bodied palate supported by firm but smooth tannins and just the right amount of acidity. That being said, it does tilt towards the leaner, less fruit-forward Old World style. The wine was aged for 18 months in 100% French oak, 43% of which was new. ABV is 14.5 %.

Note: This selection is guilty of Bloated Bottle Syndrome, which I’m calling out for bottles that weigh more than the wine they contain. The web site of nearly every winery will usually include a mention of the operation’s dedication to “sustainability” and “stewardship.” Unfortunately, this often seems only to extend to the property itself. Many “premium” wines like this one come in heavier bottles to allegedly denote quality. This one weighs in at 880 grams. (As an example of a more typical bottle, Estancia Cabernet’s comes in at 494 grams.) That’s a lot of extra weight to be shipping around the country (or the world). By comparison, the wine inside, as always, only weighs 750 grams. Even sparkling wine bottles are often about the weight of this one, and those are made to withstand high internal pressure. Unfortunately, this sort of “bottle-weight marketing” is becoming more common, especially at higher price points. But there are other ways to denote quality without weight: unusual label designs, foils, wax dipping, etc.

Plastic bottles have a lower environmental impact than glass, 20% to 40% less, in fact. And, bag-in-box packages are even less than plastic bottles. (Unfortunately, current bag technology will only keep unopened wine fresh for about a year, so they are only suitable for wines to be consumed upon release from the winery; that’s about 90% of all wine sold though.)

The carbon footprint of global winemaking and global wine consumption is nothing to scoff at, amounting to hundreds of thousands of tons per year. The latter, which requires cases of wine be shipped around the world, imprints a deep carbon footprint. Because wine is so region-specific, and only so many regions can create drinkable bottles, ground and air transportation is responsible for nearly all of the wine industry’s greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Sustainable Wine Roundtable, a group of wineries, retailers, and other companies connected to the wine industry, one-third to one-half of that total is due to the glass bottles themselves.

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/