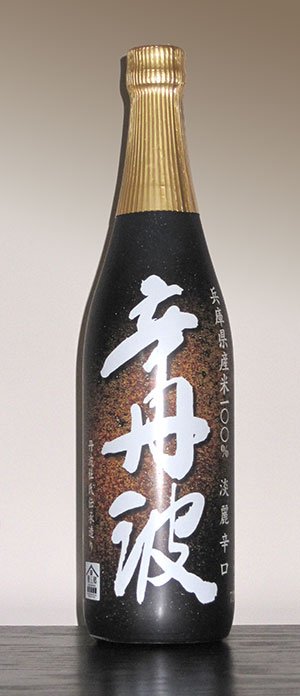

Ozeki Karatamba Saké

Saké, the national alcoholic beverage of Japan, is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is a beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit.

To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered and usually pasteurized. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

In 1711, the Manryo brewery, was established by the first Chobei Osakaya of the Osabe family in Imazu, Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture. This is a significant saké production region , and the head office is still located there. The famous water found here is known as Miyamizu, groundwater originating in the Rokko mountain system. The region is also ideal for rice production, including Yamada-nishiki, a renowned saké rice.

In 1810 the fifth-generation owner of Manryo built a lighthouse to help guide home the ships that had delivered Manryo’s products to Edo, as Tokyo was then known. The Imazu lighthose has been an important cultural edifice in Nishinomiya ever since. In 1984 it underwent an extensive restoration.

The Imazu lighthouse.

In 1884 the company was rebranded from Manryo to Ozeki. The name originates from the world of sumo wrestling, where the grand champion was originally known as the Ozeki (now the second highest rank). Additionally, odeki is Japanese for ‘good job.’ Because it sounds similar to ozeki, this was intended to motivate the production of good saké. As sumo was becoming popular in the late 19th century, it exemplified many of the ideas that were considered important for success, including strenuous hard work and technical skill. Ozeki aimed to build the brand through these concepts, just like winning sumo wrestlers try to do.

Ozeki’s facilities were destroyed by fire due to a WWII air raid in 1945, but were rebuilt following the end of the war. In 1966, Ozeki introduced a saké vending machine, something we will never see in the United States! They entered the U.S. market in 1979 by establishing Ozeki San Benito Inc. in Hollister, California. The company celebrated 300 years in business in Japan in 2011,

Ozeki Karatamba Saké

Like my wines, I prefer my sakés to be dry. Karatamba is one of the driest I have found, with a Sake Meter Value* of +7. The ABV is 15.5%, and the polish rate** is 70%.

Karatamba (Dry Wave) is brewed and bottled in Japan. It is a honjozo saké. This classification, one level up from the most basic, is made with better-quality rice, and a higher proportion of the alcohol is produced during fermentation rather than being added (a characteristic of honjozo). Also, Karatamba attains its dryness level by the added alcohol; it would be difficult to do so without it.

Predictably, this saké is crystal clear. The nose offers up melon and lychee. These continue on the palate (without the tartness) plus some caramel richness and perhaps a hint of maple syrup. It has a round smooth mouthfeel ending in a pleasant soft finish.

*An important gauge of saké is the SMV (Saké Meter Value). This measures the density of saké relative to water, and is the method for determining the dryness or sweetness of saké. The higher the SMV, the drier the saké. The range is -15 to +15.

**The rice used in saké is called “saka mai” in Japanese, and it is not the same type of rice used for eating. The grains are larger than food rice, contain more starch, and less protein and fat. The rice is first milled, aka “polished,” to remove the outer layer that could cause off-flavors in the finished product. Typically, this will be 25 to 70%, but I have heard of exotic sakés with 99% starch removal! Not surprisingly, the more the rice is milled, the more expensive the saké becomes.

www.ozekisake.com/products/product_detail.php?product=12

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/

One Reply to “Ozeki Karatamba Saké”