Three Interesting Sakés

Saké, the national alcoholic beverage of Japan, is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is a beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered and usually pasteurized. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

Here are three interesting sakés to try. All should be served chilled, or at room temperature. Although the cheap sake you may encounter in sushi restaurants will usually be heated, often too much so, such treatment will destroy the subtleties of these selections.

Nanbu Bijin “Southern Beauty” Tokubetsu Junmai

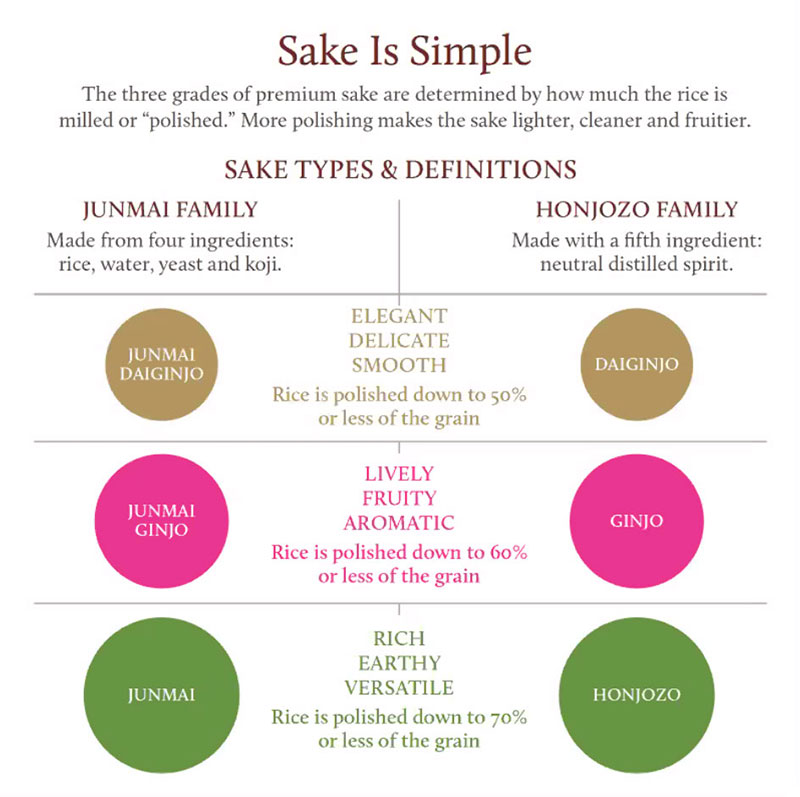

Tokubetsu translates to “special,” indicating that a special element was incorporated into the brewing process at the discretion of the brew master. In the case of this sake, that element is the use of the local Ginginga rice which took over eight years to develop and perfect, according to the brewery. The water, yeast, and brewing team are also all from Iwate prefecture. Junmai is pure rice wine, with no added alcohol. Until recently, at least 30% of the rice used for junmai sake had to be milled away, but Junmai no longer requires a specified milling rate.

Junmai is historically considered the “way saké was” and means “rice and water only,” These brews can have their rice milled to many different levels, from 80% with 20% removal to 55% with 45% removal, as long as the milling percentages are on the label. The result is that some Junmai can drink very rich and full-bodied, and some drink lighter and more elegant. They can be served chilled, at room temperature, or warmed (but I suggest avoiding warming this one).

Southern Beauty has been milled to 55%, with 45% removal of rice, as high as it gets. It is Kosher certified, unusual among sakés. It has a soft, round character, with a flavor reminiscent of mandarin oranges. ABV is 15.3%.

Tozai “Snow Maiden” Nigori Junmai

Snow Maiden, also known as Hanako, was a koi fish that lived to the age of 226 years in pure mountain water at the base of Japan’s Mt. Ontake. Nigori, or nigorizake, translates roughly to “cloudy” because of its appearance, and is the oldest style of saké. The cloudiness is produced when a brewer leaves in some of the rice lees, or sediment. Nigori is not an unfiltered saké however, as the sake is filtered to some degree. I’m not a big fan of nigori saké because of the rice grit that it always contains. It is quite delicate here, however, and I found it acceptable.

This expression is relatively dry for a nigori saké, as they always tend toward sweetness. It has been milled to 70%, and has a soft, floral palate, with flavors of cantaloupe and a suggestion of daikon. ABV is 14.9%.

Dassai 45 Junmai Daiginjo

Daiginjo is the highest grade of saké. Junmai Daiginjo has the highest milling rates in saké production, with a minimum of 50% rice polished away and 50% remaining. But that standard is often surpassed by brewers looking to push the rice milling envelope, resulting in sakés that can be milled down to 35%, down to 23%, and even 7% remaining! These sakés are always served chilled.

Dassai translates to ‘Otter Festival.’ The name comes from a local Yamaguchi legend that involves a bunch of happy-go-lucky otters showing off their fishing skills and showing us humans how it’s done properly. Back in 1981, the Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin Big Band released an album called Tanuki’s Night Out, which tells the story, in music, of Tanuki, another hard-partying otter.

Like Southern Beauty, Dassai 45 has been polished to 45% rice remaining, hence the name. The nose features a banana aroma, with lychee, green apple, and “acidic bubble gum” on the palate. AVB is 16%.

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/