Wine is ancient, relatively simple (i.e. you can make wine at home, but not a cell phone), essential for wine lovers like us, but also highly competitive, perhaps now more than ever. So, marketing is essential for producers to differentiate themselves.

Marketing roughly covers four areas: labels, advertising, influencers, and other channels.

But first, some history. I’m a new world wine guy, so I’m going to focus on California for examples, but much of this applies elsewhere as well, of course.

Thomas Jefferson was an early American proponent of wine (indeed, perhaps the first American wine snob). He was dedicated to French culture, and was particularly in favor of French and Italian wine. He rejected “the strong wines of Portugal and Spain” and selected somewhat lighter wines to accompany meals in his pursuit of what he perceived as European taste and sophistication. Wine-making and drinking were part of his vision of agrarian ideals, as well. Whether by coincidence or intent, wine marketing has tended to pursue these same ideas. In 1769, nearly coinciding with the revolution, wine cultivation came into California from Mexico and wine making became the state’s oldest industry.

The U.S. experienced waves of immigration during the nineteenth century, including people from northern Europe, German, and Italy. These immigrants brought a culture of wine consumption with them, and identified fertile wine growing possibilities in various regions, including New York, Ohio, and California, particularly Napa Valley. They and their descendants began developing better-quality domestic wines with new technologies and grape varieties.

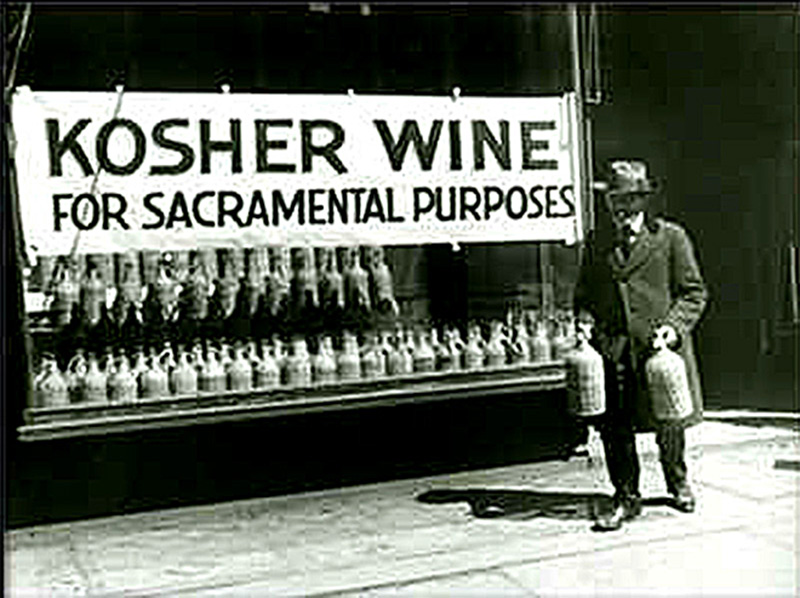

Sadly, progress in wine development was halted by the scourge of Prohibition, which lasted from 1920 to 1933. The number of licensed wineries in California plummeted from 917 in 1920 to 268 by the repeal in 1933. The wineries that survived did so by growing wine grapes for home winemakers, table grapes, and other fruits. Thousands of acres of grape vines were ripped out to make way for these other crops. (As a side note, possession of alcohol was never illegal, only buying, selling, or distributing it, hence the interest in grapes for home use.) Some fortunate wineries, including Beringer, Inglenook, Louis Martini, Wente, and others had special dispensations for producing sacramental and medicinal wines.

However, the general decimation of the industry was so great that for a number of years after the repeal, there were few trained winemakers, little usable equipment, little aged wine, and no distribution channels

In the wake of this destruction, publicist and journalist Leon Adams joined with a number of winery executives to found the Wine Institute, an advocacy group for the California wine industry, in 1934. (The Institute flourishes to this day.) Even with improved quality, in the decades prior to prohibition many American wine drinkers preferred sweet wines with alcohol added, so-called fortified wines, which include ports and sherries. The Institute lobbied the federal government to amend regulations to prohibit the use of the word “fortified” in any advertising or labeling. By replacing the term “fortified wine” with “dessert wine,” producers aimed to eliminate the general association of wine at the time with low-quality booze and excess consumption. Dessert wine was defined as wine with more than 14 percent alcohol content, and at the same time proposed the term “table wine” to designate non-sparkling wine with not over 14 percent alcohol. The table wine was also intended to associate wine drinking with dining, rather than consumption for its own sake.

Although the regulations were changed, even by the mid-1950s a market study found that 90 percent of the American public still associated California wines with inexpensive jug wines and cooking wine. That was soon to change. (By the way, never cook with a wine that you wouldn’t drink on its own. Cooking wine is loaded with salt and is made from the absolutely worst quality wine.)

Wine producers have traditionally, and perhaps accurately, seen their customers as having limited expertise, and are frustrated that buyers demonstrate inconsistent and difficult-to-predict preferences. This is why, beginning in the 1960s, rather than seeking out and responding to consumer input, they endeavored to to guide consumer tastes directly.

This either coincided with, or perhaps drove, a remarkable growth of wine consumption in the United States. The U.S. is now the largest wine consuming nation in the world, exceeding the wine-producing European countries such as France and Italy, which had for centuries had dominated world markets.

On many levels, the late 1960s and 1970s were the major turning point in the U.S. wine industry, with businesses reinventing the image of wine from a cheap and very alcoholic beverage to a sophisticated natural product, and an accompaniment for gourmet food. More and more, wine was promoted as a symbol of social status. (It became a reinforcer of social and class divisions as well but that’s a discussion for another day.)

The development of American wine culture during these years saw the birth and growth of a symbiotic relationship between industry advocacy groups, wine companies, grape farmers, newspaper and magazine journalists, and consumers.

The first and most obvious marketing tool is the wine label

In the tomb of King Tutankhamen wine jars were discovered that had markings with enough details to allegedly meet some present day countries’ existing wine label laws.

The oldest paper wine label on record was from French monk Pierre Perignon, he of champagne Dom Perignon fame. (Dom Perignon isn’t a champagne house, it’s a brand. The producer is Moet & Chandon.) His wine label was made of parchment and was tied to the neck of the bottle with a simple piece of string.

By the early 1700s, with the wide-spread introduction of glass bottles and the multiple varieties of wine being produced, there was a need to identify wines by their origin and their quality. This was the birth of the modern wine label.

But wine labels really got going in 1798. This was the year Czechoslovakian Alois Senefelder invented lithography, which is the basis of all modern printing presses. Suddenly, lithography allowed for printing wine labels in mass quantities, with intricate detail, and multiple colors. Most wine producers preferred wine labels in a rectangular shape that allowed room for increased information about the wine, and it is still the most common format today. It’s also the easiest and most efficient way to get multiple labels out of a single large sheet.

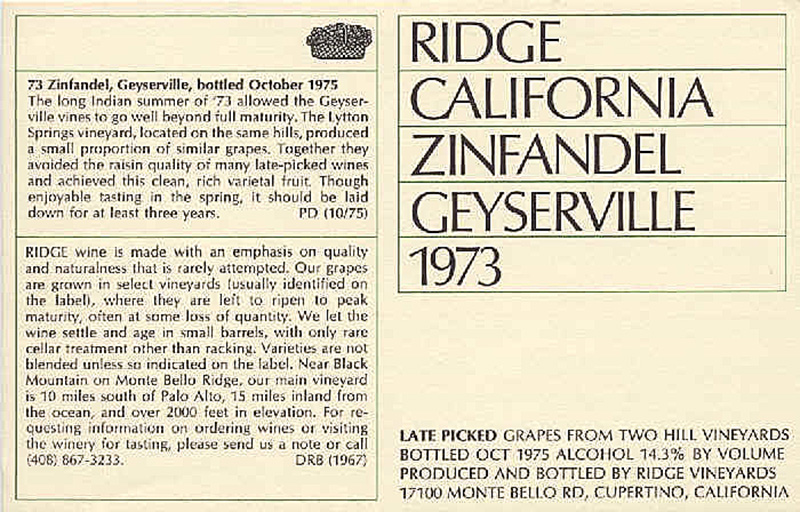

A wine label can and frequently does communicate many different types of information. Obviously, it can be a document of its contents and nature. It can communicate the principles, and competency of a winemaker. It can express a winery’s philosophy or concept. It can honor the history of the wine. It can signal whether the wine is fun or serious.

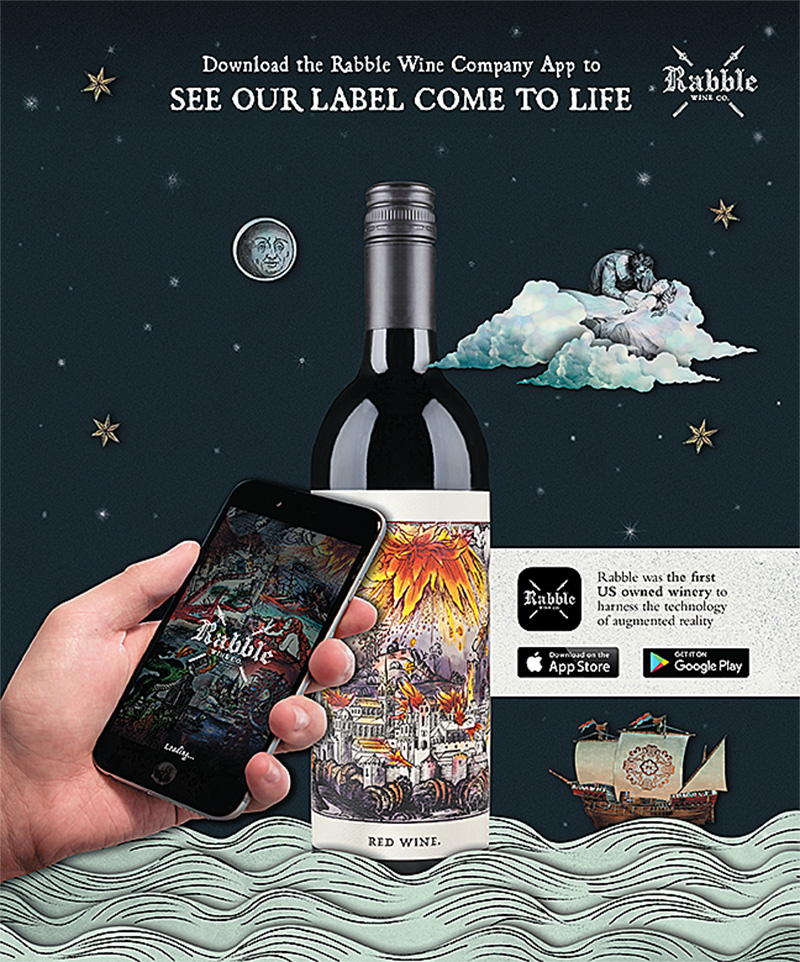

In addition to the traditional label content, some wineries have begun to use a “QR code” which can store all kinds of additional information and interesting facts consumers may like to know about the product.

Wine – now more than ever via social-media – supports a very special form of bragging rights, and the label is crucial to this. Is it selfie ready? Is it beautiful? Is it something no one has seen before? Does it look like something made in small volume or from a single-vineyard, thus signaling the drinker is in on something rare and exclusive?

The typical wine buyer wants to be confident they are making a good decision in the selection of a product, and they want to trust that their judgment in their selection is sound, and a well-designed label will reinforce this desire.

Next, the role of advertising and media.

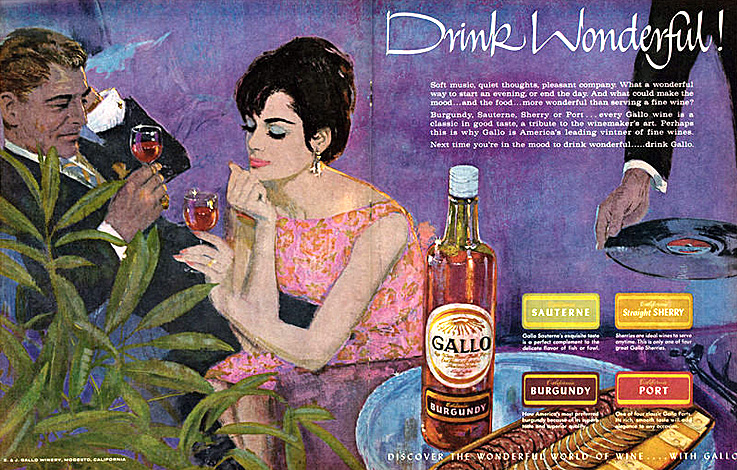

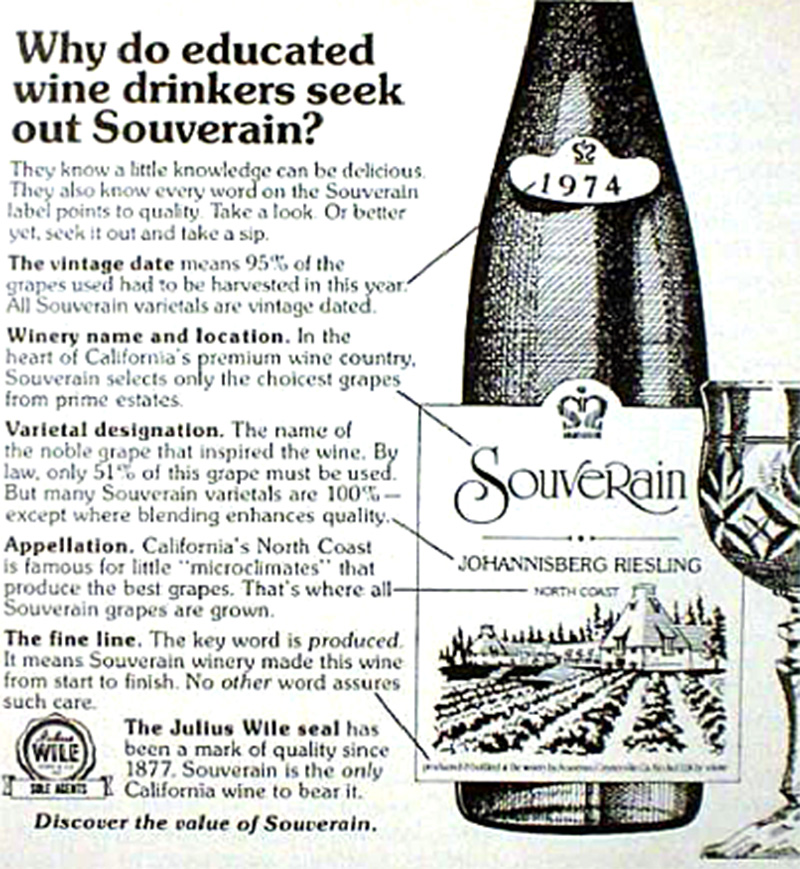

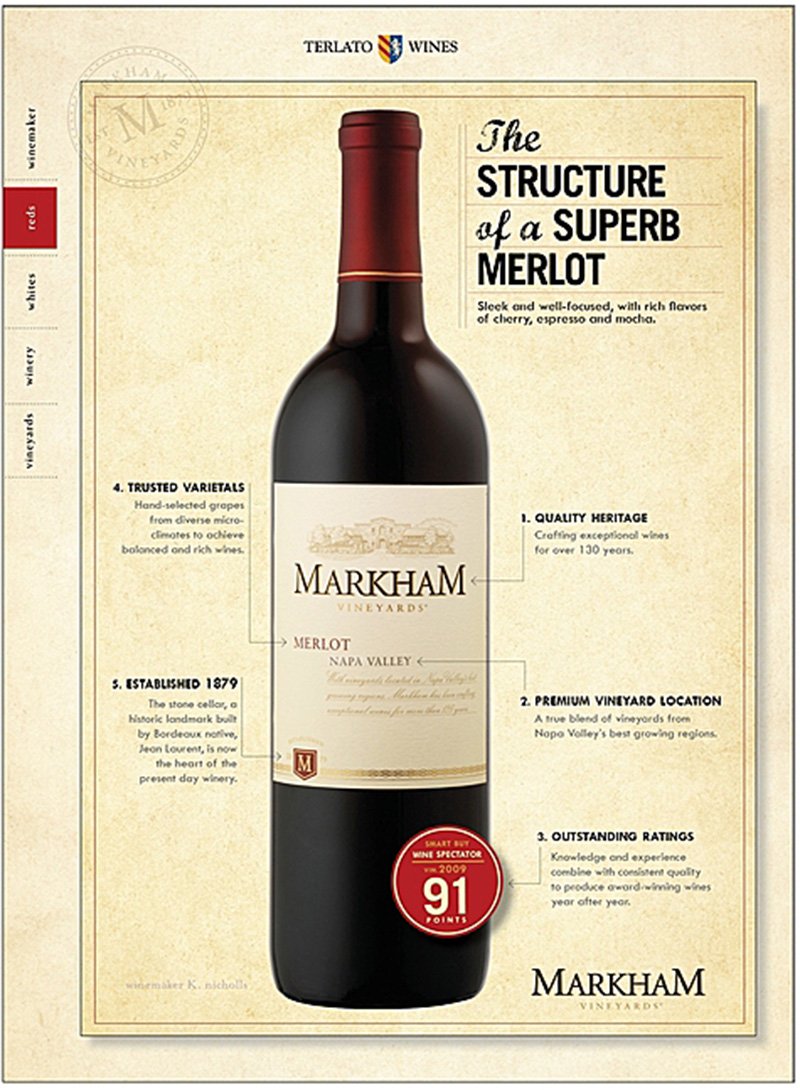

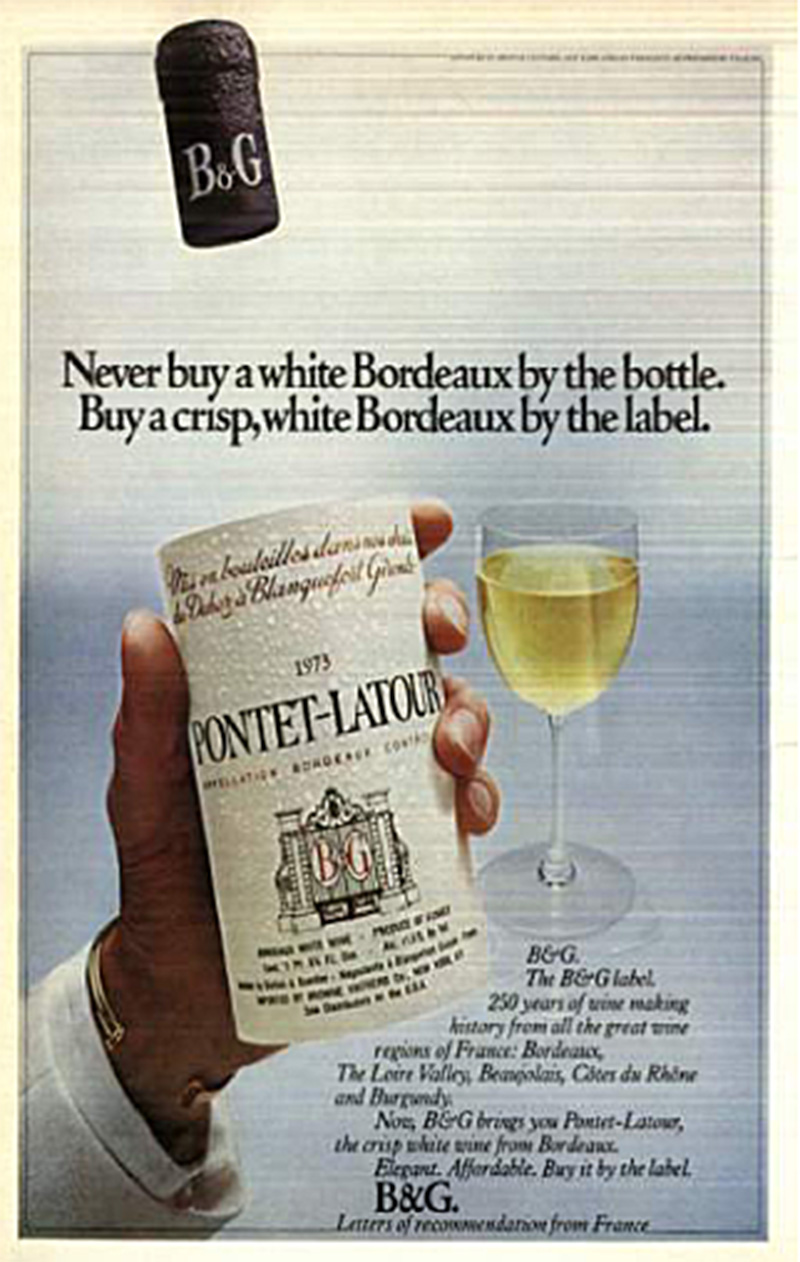

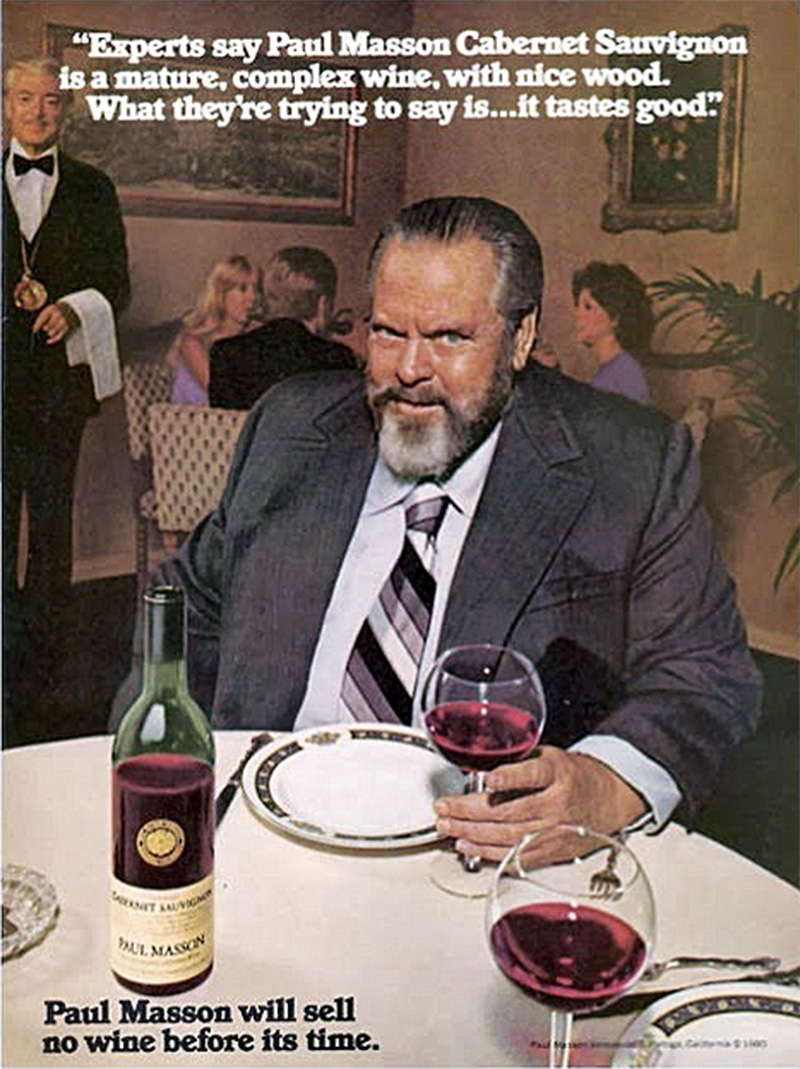

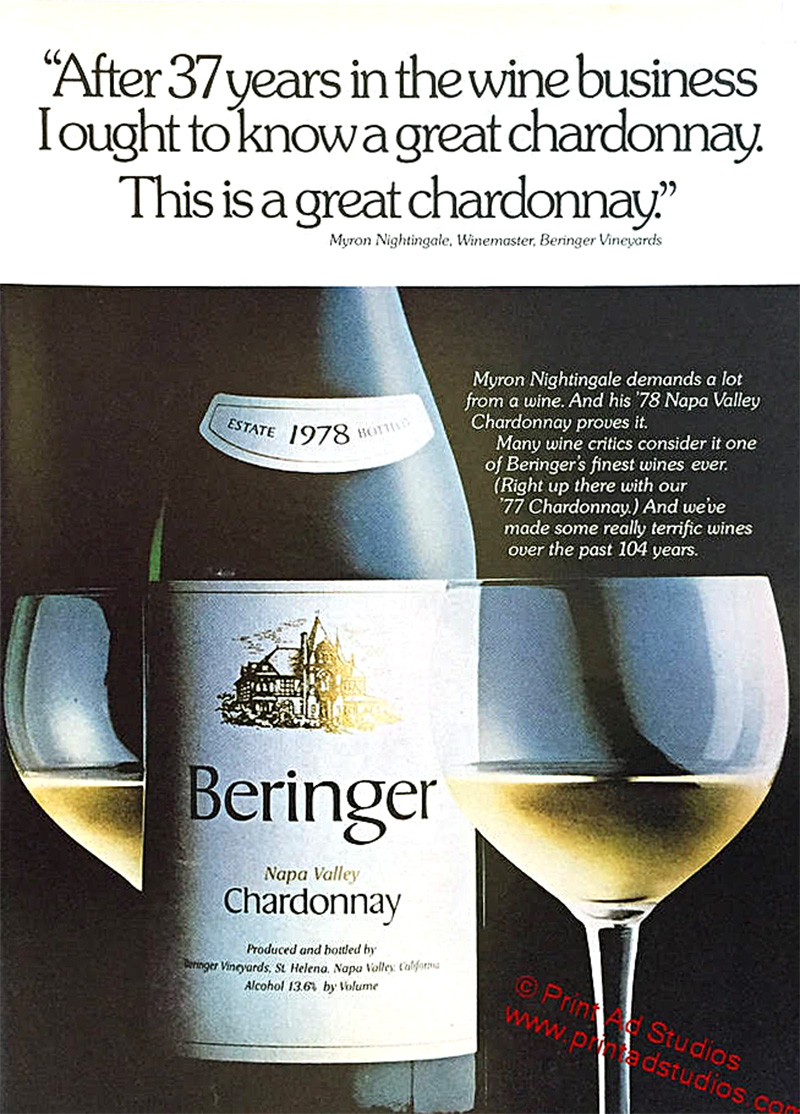

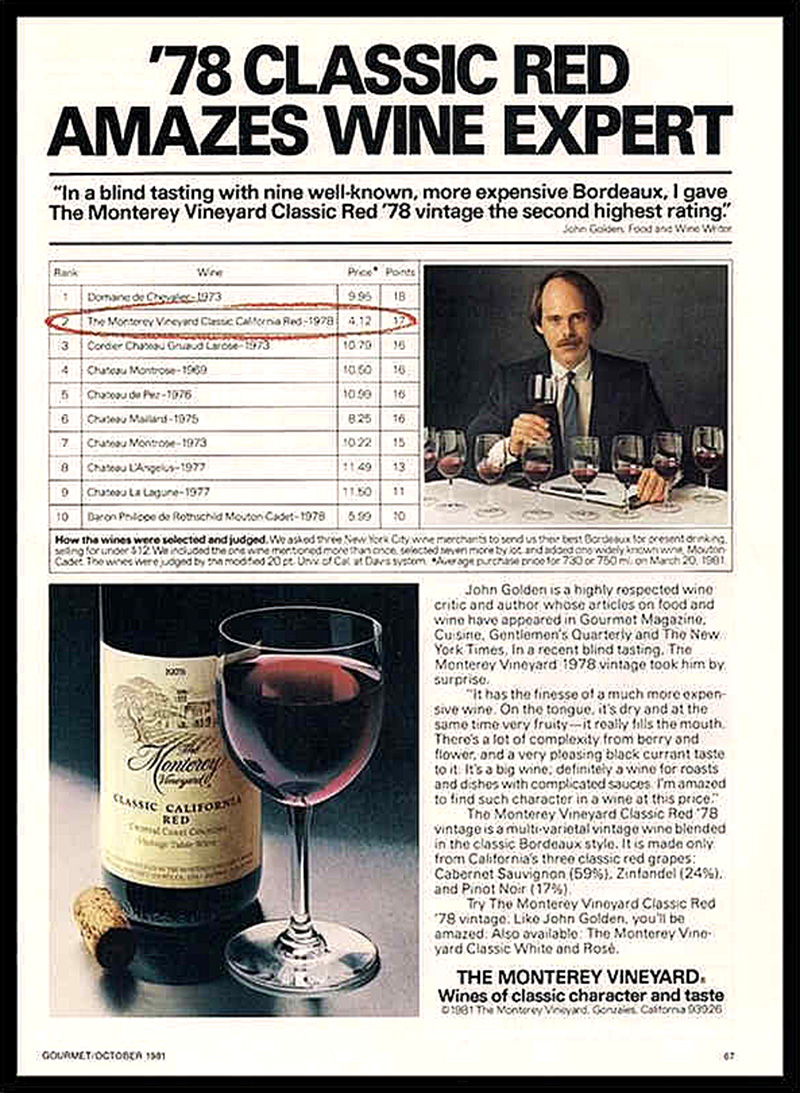

In the ’60s and ’70s, many wine advertisements tried to serve as buying manuals for consumers, instructing them in which part of a label provided what kind of information. These advertisements also drove a specific brand name to look for at a store, of course, while sometimes downplaying intricate information such as vintage year and grape varietals.

Advertisements thus told consumers explicitly to look for their labels, often suggesting that the producer’s brand name was at least as important as the taste of a particular type of wine, so the buyer would be freed from error when making a purchase.

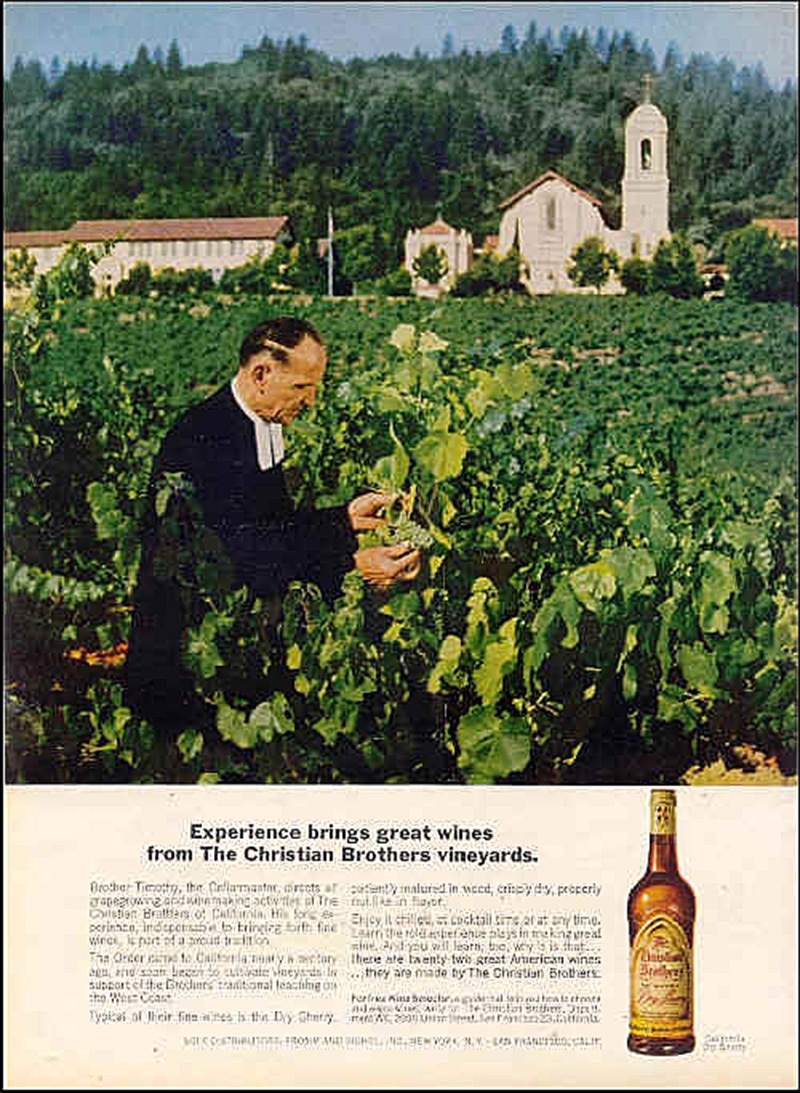

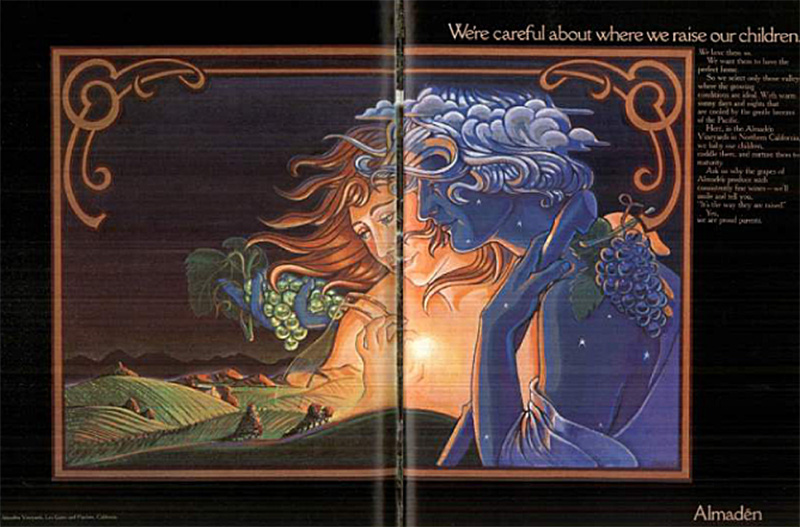

Especially after Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, some Americans increasingly became conscious about environmental issues. In addition, consumer rights and counter-cultural movements attacked endless economic growth, industrialization, and materialism. In emphasizing the relations between wine and natural resources, wine companies sought to create a popular image of wine as a product of nature. In so doing, in their advertising they presented themselves as defenders of a Jeffersonian, pastoral ideal, perhaps somewhat cynically even as much of the American wine industry became ever more industrialized.

In what is perhaps the single most important media event in American wine history, on June 7, 1976, Time magazine correspondent George Taber reported the triumph of California wines at the Paris Wine Tasting in his article entitled the “Judgment of Paris.” At this blind tasting contest of Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon from France and California, presided over by an all-French judging panel, California wines rated best in each category.

New York City’s Acker Merrall & Condit claims to be “America’s oldest wine shop.” By noon of the day after Taber’s story appeared, the store sold out of the five cases of wine it had from Chateau Montelena and Freemark Abbey, the two California wineries that had participated in the Paris Tasting in the white wine section. The former had ranked first and the latter winery seventh out of ten participants, forever altering the American wine industry and igniting the boom in American interest in wine that continues to this day. (By the way, Stag’s Leap won the red wine category. The 2008 movie Bottle Shock dramatized this contest, and I recommend it. As of this post, It’s on Amazon Prime if you have a subscription, or for $3 on youtube,)

Building on this success and recognition, Napa Valley winery owners were among the first to make a wine-growing area a tourist destination, developing yet another seductive marketing tool. Shrewdly, they began selling more than just a beverage—they were selling the place, the lifestyle, and the connection with sociability and good food.

Predictably, this also led to an investment boom in California vineyards. (Remember, there were 268 wineries in the state by the repeal in 1933. That number had fallen to 240 in 1970, still a more or less steady figure for 37 years. In 1983, just 13 years later, the number of producers had grown to 550, more than doubling. Now, 37 years after that, there are 3,674 wineries, or a growth rate of 1430% in 50 years. (Total U.S. wineries are now 8,702, so the dominance of California is quite apparent.)

The promise of profits drew large diverse companies from outside the wine industry. For instance, Heublein bought inglenook and Beaulieu, Coca-Cola bought Sterling), Pillsbury acquired Chateau Souverain, and and Nestle purchased Beringer. As these and other companies started to invest in California wine, they reinforced business strategies that focused on brands, advertising and marketing campaigns, and hoped-for stable and high returns. (However, almost all of these corporations have since left the wine business. There is an old maxim: if you want to make a million dollars by making wine, the first thing you need to do is spend a million dollars. And winemakers are often driven as much by passion, a quality lacking in large corporations, as they are profits)

Influencers (like journalists and bloggers)

Wine producers, like many other businesses, have often attempted to shape and direct markets themselves, and continue to do so. They build influential relationships with industry movers and shakers. They educate these experts in their histories, winemakers, and visions for the future, and thus hope to gain some control over their stories that reach the public. They provide the language and knowledge needed to help people discover and appreciate their wines.

Naturally, consumers looking to buy a bottle of wine confront thousands of choices. In fact, in surveys many wine shoppers describe the experience as stressful; they are fearful of making a poor choice and looking ignorant or of missing an opportunity to make an evening more special. To navigate a sea of wine, they invariably turn to those experts that the wineries have worked so hard to enlist.

There are serious questions about the objectivity of wine scores and how they are arrived at (that’s why there are none here at Winervana). Regardless, critics still have a profound influence on the behavior of retail and hospitality buyers and consumers. One retailer conducted an experiment in which he displayed two comparably-priced California Chardonnays next to each other on the shelf, and prominently posted their Wine Advocate scores and tasting notes below the bottles. The bottle with a score of 92 outsold the bottle with a score of 85 by ten to one. In a later match-up, when the same wines were displayed with tasting notes only, sales were roughly even.

Other channels

Wine Clubs

Nearly every major winery offers a wine club, where members commit to purchasing a set number bottles of wine on a regular basis, in exchange for a significant discount, invitations to members-only events, access to members-only selections, and unlimited free tastings at the winery. Wine clubs cultivate repeat business and provide sustainable cash flow that can be counted on throughout the year.

Wine club sales reportedly make up 33% of the average winery’s income, and that number increases for wineries that make fewer than 2,500 cases of wine each year. Consumers spent more than $3 billion in direct shipments in 2018, according to the 2019 Direct-to-Consumer Wine Shipping Report, from a company which helps wineries maintain Direct-to-Consumer (D2C) operations,

Event Hosting

Although temporarily suspended due to Covid-19 obviously, many wineries host business events, weddings, and summer concert series on their properties, and no doubt will again once it is safe to do so These events are a great way to increase exposure as well as revenue.

Finally, there is the entire spectrum of Social Media

According to the aforementioned D2C consulting company, “Social media represents a direct line of communication to consumers to tell the sort of behind-the-scenes story that can forge a lasting, personal connection. Instagram, in particular, can help wineries virtually extend the tasting room experience to drive demand for both online shipments and in-person visits. Creating strong content that audiences can engage with raises brand awareness and affinity with consumers, and sophisticated marketers can use online ads to engage recent website visitors and even past customers that are less engaged.”

Over many years, wine enthusiasts, the wine industry, and the wine press have worked together to position wine as something chic and sophisticated, and have largely succeeded.

But it’s important to remember wine is also, at its core, just part of any good meal and for enjoying time with friends.

The origins of Emilio Lustau S.A. date back to 1896, when José Ruiz-Berdejo, a secretary to the Court of Justice, started cultivating the vines of the family’s estate, Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza, in his spare time. In these modest beginnings he made wines which were then sold to larger sherry producers. This activity was known as being an almacenista or stockeeper.

The origins of Emilio Lustau S.A. date back to 1896, when José Ruiz-Berdejo, a secretary to the Court of Justice, started cultivating the vines of the family’s estate, Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza, in his spare time. In these modest beginnings he made wines which were then sold to larger sherry producers. This activity was known as being an almacenista or stockeeper.

Winter is behind us for yet another year, and even under quarantine, thoughts turn to relaxed evenings on the deck or patio, steaks or shrimp sizzling on the Weber, and something cool and refreshing in the glass. A crisp Chardonnay or ice-cold beer are nice, of course, but it’s hard to beat a well-made Margarita (no sweet-and-sour mix!) when the weather gets pleasant. And, of course, Cinco de Mayo is just a couple of days away as I write this.

Winter is behind us for yet another year, and even under quarantine, thoughts turn to relaxed evenings on the deck or patio, steaks or shrimp sizzling on the Weber, and something cool and refreshing in the glass. A crisp Chardonnay or ice-cold beer are nice, of course, but it’s hard to beat a well-made Margarita (no sweet-and-sour mix!) when the weather gets pleasant. And, of course, Cinco de Mayo is just a couple of days away as I write this.