A winemaker, Nicole Walsh of Ser Winery, recently recommended a wine to me. And I thought, “If a winemaker recommends someone else’s product, it must be worth seeking out.” That wine? Hedges Family Estate Red Mountain Syrah.

In June of 1976, Tom Hedges and Anne-Marie Liégeois married in a 12th century church in Champagne, France, the area where Liégeois was born and raised. This melding of New World and Old World experiences and sensibilities would directly inform them once they entered the world of wine years later.

Liégeois was born near the medieval town of Troyes. Her upbringing was “maison bourgeoise,” where three generations of the family lived and worked together. The family was prosperous, and could afford to enjoy traditional home-cooked meals and the best of the local wines.

Hedges was raised as a “traditional” American, in a home of strong work ethics guided by his father, who had a background in apple growing and dairy farming before becoming an engineer. The younger Hedges was born in Richland, Washington, located at the confluence of the Yakima and Columbia Rivers. It was established in 1906 as a small farming community, but in 1943 the U.S. Army turned much of it into a bedroom community for the workers on its Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb at the nearby Hanford Engineering Works (now the Hanford site). The B Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium production reactor in the world, was built here. Plutonium manufactured at the site was used in the first nuclear bomb, which was tested at the Trinity site in New Mexico, and in Fat Man, the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan. Nuclear weapons development continued here throughout the Cold War. Now now-decommissioned, Hanford leaves behind a grim legacy of 60% of the high-level radioactive waste managed by the US Department of Energy, including 53 million US gallons (200,000 m3) of high-level radioactive waste stored within 177 storage tanks, 25 million cubic feet (710,000 m3) of solid radioactive waste, and areas of heavy technetium-99 and uranium contaminated groundwater

Tom Hedges spent the first ten years of the marriage working for large multinational agricultural firms. He was employed by Castle & Cooke foods from 1976 to 1982 where he headed up four international offices. Next, he worked for Pandol Bros., a small Dutch trading company in Seattle, which at the time was importing Chilean produce and exporting fruit to the Far East and India. In 1984 he served as President and CEO of McCain Produce Co. in New Brunswick, Canada, farming potatoes for export. Then, in 1986, the Hedges created an export company called American Wine Trade, Inc., based in Kirkland, Washington (which is also the home of Costco), and began selling wine to foreign importers, primarily in Taiwan. As the company grew, it began to source Washington wines for a larger clientele, leading to the establishment of a negociant-inspired Cabernet/Merlot blend called Hedges Cellars in 1987. This wine was sold to the Swedish government’s wine and spirit monopoly, Vin & Sprit Centralen, which was the company’s first major client.

During this time, the Hedges discovered the developing wine region called Red Mountain, three hours southeast of Seattle. After buying fifty acres here in 1989, they planted forty acres to Bordeaux grape varieties and transformed American Wine Trade from a negociant and wine trader into the classic model of a wine estate. Today, this Biodynimacally-farmed Red Mountain property continues to be the core of the Hedges family wine enterprise. In 1995, they began construction of the Hedges Chateau.

Hedges Chateau. Photo: Jacob Hughey

The Hedges ‘children, Sarah and Christophe, are now involved in the business, and each has a special set of skills for understanding the terroir.

Sarah attended the University of San Diego and graduated with a degree in business and philosophy. She later attended UC Santa Barbara to study chemistry, and at the same time worked for a Santa Barbara winery managing the tasting room and helping with harvest. From 2003 to 2005 she worked for Preston Vineyards in Healdsburg, Sonoma County, doing wine production work. She became assistant winemaker for Hedges in 2006 under the tutelage of her uncle, Pete Hedges (younger brother of Tom). Pete Hedges schooled Sarah in both terroir and chemistry, believing that each works to show a wine the path to exhibit the truth of its place. Sarah ascended to head winemaker in 2015 after her uncle retired.

The elder of the two, Christophe, is a graduate of the University of San Diego with a Business Degree and minor in Theatre Arts. In addition to being the general manager at Hedges, he farms his own property using modern Biodynamic techniques, executed by John Gomez, the Hedges Family Estate vineyard manager. He has been long opposed to the numerical point scores used by several wine critics, and he urges consumers to rely on their own knowledge about a specific varietal or the region from which it came. (I’m with you there, Christophe!) Ten years ago he created scorevolution.com, an online petition promoting the elimination of 100-point rating scales from wine reviews altogether. “The final decision about a wine is personal, and it belongs to the wine drinker alone,” he explained. (As of this writing, the site is still online, but seems to be closed to any further activity. I.E. you can’t even read the manifesto, much less endorse it, which I would have been happy to do. Regardless of where you stand, you can read a criticism and defense of the point-score system here.) Christophe is also responsible for the very European-style Hedges bottle labels.

Hedges Cellars eventually transitioned to Hedges Family Estate, and farming practices have become more focused towards being organic and vegan. Rather than commercial strains, only wild yeast is used, and the wines are neither fined nor filtered. They are also gluten free. The Hedges estate vineyard is certified organic by CCOF, nonprofit organization that advances organic agriculture for a healthy world through organic certification, education, advocacy, and promotion. It is certified Biodynamic by Demeter, the only certifier for Biodynamic farms and products in America. While all of the organic requirements for certification under the National Organic Program are required for Biodynamic certification, the Demeter standard is much more extensive. The vineyard is also rated by Salmon Safe, which works with West Coast farmers, developers, and other environmentally innovative landowners to reduce watershed impacts through rigorous third-party verified certification.

Hedges estate vineyard. Photo: Jacob Hughey

Hedges Family Estates Red Mountain Hedges Vineyard Syrah 2017

The grapes are from the Hedges Estate Biodynamic vineyard. After being harvested they were crushed into bins where they underwent indigenous yeast fermentation. After pressing, the wine was aged in barrel where it underwent indigenous malolactic fermentation. The wine was aged in 56% new oak (65% French and 35% American) for 22 months before bottling.

This Syrah pours a nearly opaque dark purple into the glass. There are full aromas of dark stone fruits accompanied by earth. On the palate, those flavors are rather recessive, in the European style, but primarily pomegranate, and blueberry. Or it might just be that they are being masked by the big, black-tea tannins. These come with good supportive acidity. 259 cases were made, and the ABV is 13.5%.

Hedges Family Estates C.M.S Cabernet Sauvignon 2018

The grapes were sourced from the Sagemoor, Wooded Island, and Bacchus vineyards in the Columbia Valley AVA and Hedges Estate, Jolet and Les Gosses vineyards in the Red Mountain AVA. The must was pumped-over for eight days and pressed to tank, where it underwent malolactic fermentation. The Columbia Valley portion of this wine (59%) was fermented to dryness in 100% American oak and aged in 100% French oak. It was then barrel aged for five months in 100% neutral oak. The Red Mountain AVA wines (41%)were barrel aged in 100% neutral American and French oak for 11 months.

C.M.S (named for its blend of 76% Cabernet Sauvignon, 8% Merlot, and 16% Syrah) is a semi-transparent but deep red. The rich aromatics feature blueberry, blackberry, and black cherry, with support from dark cocoa and vanilla. These deploy in the mouth as the same flavors. Both the acidity and tannins are excellent and harmoniously balanced. 5976 cases were produced, and the ABV comes in at 14.0%.

Descendants Liegeois Dupont 2011

This Syrah is an homage to both sides of Anne-Marie Hedges’ French families. the Liegeoises and Duponts. The fruit was sourced from the Les Gosses vineyard in the center of the Red Mountain AVA. The juice was pumped over on skins for eight days before pressing to barrel and undergoing malolactic fermentation. The wine was barrel aged for an average of 12 months in 52% new oak and 48% older oak( 62% American, 31% French, and 7% Hungarian).

The wine pours a semi-transparent dark purple color. It shows full aromas of dark stone fruit, especially plum, bordering on prunes, with hints of maple bacon. leather, and smoked cedar. The plums plus blueberry are revealed on the palate. The ABV is 14%, but seems higher due to the wine’s richness. It’s all supported by strapping tannins and plenty of tart acidity. 1202 cases were made.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

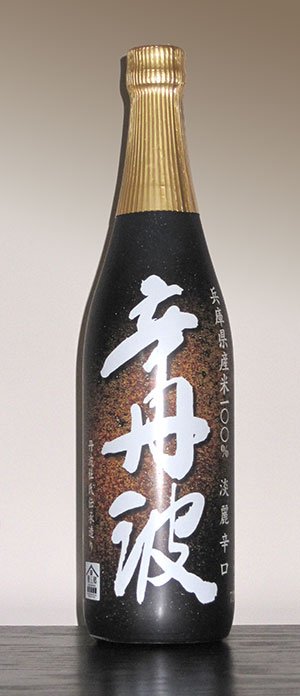

Let’s be clear about this right away: Saké, the national alcoholic beverage of Japan, is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is a beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit.

Let’s be clear about this right away: Saké, the national alcoholic beverage of Japan, is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is a beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit.

In 1884 the company was rebranded from Manryo to Ozeki. The name originates from the world of sumo wrestling, where the grand champion was originally known as the Ozeki (now the second highest rank). Additionally, odeki is Japanese for ‘good job.’ Because it sounds similar to ozeki, this was intended to motivate the production of good saké. As sumo was becoming popular in the late 19th century, it exemplified many of the ideas that were considered important for success, including strenuous hard work and technical skill. Ozeki aimed to build the brand through these concepts, just like winning sumo wrestlers try to do.

In 1884 the company was rebranded from Manryo to Ozeki. The name originates from the world of sumo wrestling, where the grand champion was originally known as the Ozeki (now the second highest rank). Additionally, odeki is Japanese for ‘good job.’ Because it sounds similar to ozeki, this was intended to motivate the production of good saké. As sumo was becoming popular in the late 19th century, it exemplified many of the ideas that were considered important for success, including strenuous hard work and technical skill. Ozeki aimed to build the brand through these concepts, just like winning sumo wrestlers try to do. When I profile a wine, I like to start with the story of the producer, and then get into the wine itself. I couldn’t find much about this offering, which is just as well as it is low-quality plonk.

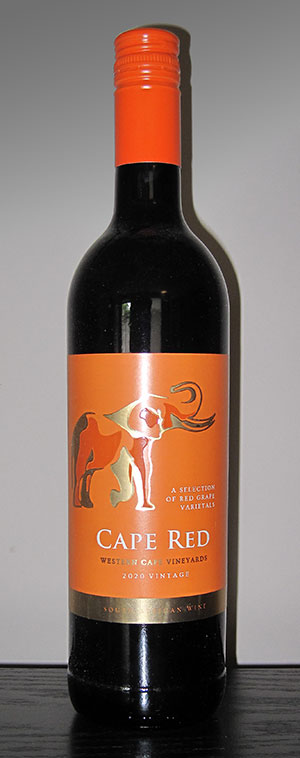

When I profile a wine, I like to start with the story of the producer, and then get into the wine itself. I couldn’t find much about this offering, which is just as well as it is low-quality plonk.