I’m obviously a wine enthusiast, and with my wife will drink all or most of a full bottle of wine with dinner just about every night. However, you may enjoy less wine with your meals. If so, consider 375 mL half bottles. They are also handy if you want a red and your companion wants a white, like the two shown here. Half bottles are also convenient for picnic outings. And, empty half bottles are great for storing leftover wine; just fill the half bottle as close to the top as you can, reseal it (easily done if the closure is a screw cap), and park it in the refrigerator.

I’m obviously a wine enthusiast, and with my wife will drink all or most of a full bottle of wine with dinner just about every night. However, you may enjoy less wine with your meals. If so, consider 375 mL half bottles. They are also handy if you want a red and your companion wants a white, like the two shown here. Half bottles are also convenient for picnic outings. And, empty half bottles are great for storing leftover wine; just fill the half bottle as close to the top as you can, reseal it (easily done if the closure is a screw cap), and park it in the refrigerator.

The only real downside to half bottles is that they will cost somewhat more than half what the same wine in a full bottle will, since, other than the wine itself, the remaining expenses of filling, labeling, packing and shipping are more or less the same as for a full bottle. For instance, the Chardonnay is $15 for a half bottle, and $26 for a full one. Similarly, the Pinot Noir is $15 for a half bottle, and $29 for a full one (but really, not much of a penalty on this one). Finding your favorite wines in half bottles can also sometimes be difficult, although like wine in cans they are becoming more common. And now, on to the wines.

One fine spring day in 1972, attorney, private pilot, and wine aficionado Fred Fruth was piloting his plane over the Russian River Valley area. Down below, he saw a natural amphitheater carved into the hills of eastern Sonoma. In addition to this other interests, he had been thinking of starting a winery, and it seemed as if this might just be the place to do it.

Fred Furth Fred Furth

|

Soon after, a tour of the extensive property confirmed that the site indeed had the climate and soils to grow first-class wine grapes. Furth and his second wife, Peggy, purchased the land, named the estate Chalk Hill, and started producing wine about a decade later. They gradually planted more than 270 acres of vines. Years later, Furth said, “I have always been interested in wine because my grandfather had vineyards. I’m actually more interested in the working-the-soil aspect, but I have many very talented people in the winery who know how to produce a world-class wine. When I bought this property, I was told it was too hilly to be a vineyard, but I simply planted the grapes in rows going uphill. People said you can’t do that, but I’d seen it done in Germany so I knew it would work.” After a rich and varied life, Furth died in 2018 at the age of 84.

Bill Foley Bill Foley

|

Lawyer Bill Foley acquired Chalk Hill in 2010. Although Foley is titled as “vintner,” I doubt he sees the interior of the winery very often. He is a vintner in the broader sense of “someone who sells wine.” He also owns the National Hockey League’s Vegas Golden Knights, is the Executive Chairman of the Board of Directors for Fidelity National Financial Inc., is Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors for Fidelity National Information Services, Inc., and owns fifteen other wineries.

The Estate

x

x

The Chalk Hill AVA is one of 13 in Sonoma County, and is distinguished from the neighboring appellations of the cooler Russian River Valley to the west and the warmer Alexander Valley to the northeast. Elevations are higher and soil fertility is lower. The soils include gravel, rock, and heavy clay. Under the topsoil is a distinctive layer of chalk-colored volcanic ash which inspired the name of Chalk Hill.

x

x

Each vineyard block has been planted based on criteria that include: soil profile and chemistry, slope, orientation to the sun, and climate. Under Fred Furth’s direction, Chalk Hill was an early leader in planting its hillside vineyards “vertically,” following the rise of the terrain, rather than across it. Because of this, the topsoil must be protected with a diverse cover crop serving many purposes. It anchors and protects the soil, preventing erosion; captures and affixes nitrogen; and harbors a varied community of beneficial insects that aid in pest management. Water conservation is addressed through a precisely controlled drip-irrigation system. Air movement through these vertical channels of the vineyard reduces mildew. All of the grapevines are a grafted combination of plants: a specific wine-grape variety above ground, and a complementary rootstock below.

Photo: devonwayne.com

More than two-thirds of Chalk Hill’s 1300 acres remain uncultivated. In addition to the vineyards, the property features wilderness areas, the winery, a hospitality center, a culinary garden, a residence, stables, and an equestrian pavilion.

The Winemakers

Michael Beaulac, Senior Winemaker

Michael Beaulac Michael Beaulac

|

Beaulac, a Vermont native, has as of this writing just become senior winemaker, bringing with him over thirty years of experience. He began his winemaking career when Tim Murphy of Murphy-Goode offered him a job as a harvest intern in 1989. Immediately after and through 1991 he worked as a cellar master with long-time Russian River winemaker Merry Edwards. Beginning in 1997, he spent four years as winemaker for Markham Vineyards in St. Helena. He became Vice President of St. Supéry Vineyards in Rutherford in 2001, working closely with Michel Roland and Denis Dubourdieu. Beaulac was general manager and winemaker at Napa’s Pine Ridge Vineyards from 2009 until coming to Chalk Hill this year.

Michael shared, “Be proactive in the vineyards. Let the fruit find its balance. Do not force the wine to be anything it’s not. Let it express [itself]. Once in the winery, the wine should be touched as little as possible. In a perfect vintage, we really shouldn’t have to do anything.”

Darrell Holbrook, Winemaker

Darrell Holbrook Darrell Holbrook

|

A Sonoma County native, Holbrook spent his childhood among the vineyards there. By age 12, he often accompanied his father to his job at Lytton Springs Winery, [now Ridge Vineyards] driving tractors and helping where he could. In 1994, after working at Lytton Springs in the vineyards, he began an apprenticeship under David Ramey, Chalk Hill’s winemaker at the time. He worked his way up from a cellar intern (aka cellar rat) to enologist and production manager, and then assistant winemaker in 2009. Ten years later he was promoted to winemaker.

Courtney Foley, Vintner

Courtney Foley Courtney Foley

|

The youngest daughter of Chalk Hill Estate proprietors Bill and Carol Foley, she studied enology and viticulture at both Napa Valley College and Fresno State University. Her practical experience began under winemaker Leslie Renaud at Lincourt Vineyards and Foley Estates (surprise!) in Santa Barbara County. Once back in Sonoma, she again found herself working with Renaud at Roth Estate Winery in Healdsburg. Just in case the wine thing doesn’t work out, she also has a J.D. degree with a focus on Environmental and Ocean Law from the University of Oregon School of Law.

Chalk Hill Chardonnay 2018

This offering underwent 100% malolactic fermentation, followed by 10 months of sur lie barrel aging in French, American, and Hungarian oak, of which 25% was new. It is rather pale for a Chardonnay, but that doesn’t mean it’s insipid. It features moderate aromas of citrus and melon, which continue on the palate, plus some vanilla custard. It has a full, unctuous mouthfeel, and plenty of zippy acidity. ABV is 14%.

Chalk Hill Pinot Noir 2017

This wine also underwent 100% malolactic fermentation, followed by nine months of aging in French oak, of which 25% was new. It presents with a transparent, light to medium purple in the glass. It is mildly aromatic, with flavors of raspberry, tart cherry, and a bit of dust on the medium body. Enjoy this easy-sipping Pinot now. ABV is 13%.

https://www.chalkhill.com/

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

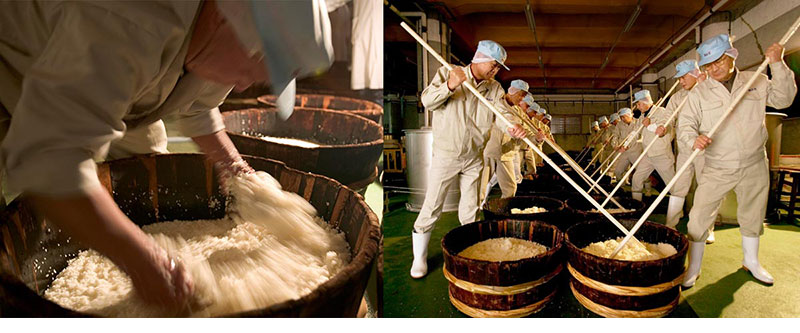

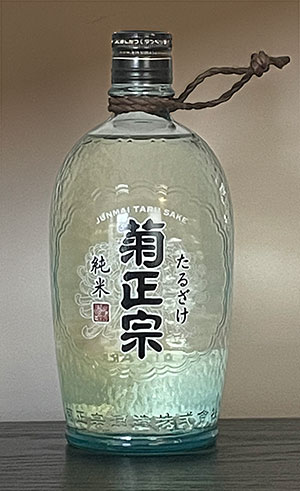

Saké is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is an alcoholic beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered, heated, and placed in casks for maturing. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

Saké is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is an alcoholic beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered, heated, and placed in casks for maturing. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

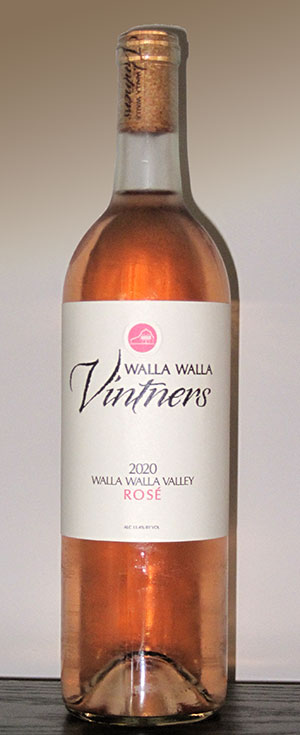

Walla Walla Vintners was founded in 1995 in the shadow of the Blue Mountains by pioneering winemakers Gordy Venneri and Myles Anderson, and was just the

Walla Walla Vintners was founded in 1995 in the shadow of the Blue Mountains by pioneering winemakers Gordy Venneri and Myles Anderson, and was just the

The brothers Dragonette (John, the elder, and Steve, the younger) and close friend Brandon Sparks-Gillis, after having met and worked together at

The brothers Dragonette (John, the elder, and Steve, the younger) and close friend Brandon Sparks-Gillis, after having met and worked together at

I’m obviously a wine enthusiast, and with my wife will drink all or most of a full bottle of wine with dinner just about every night. However, you may enjoy less wine with your meals. If so, consider 375 mL half bottles. They are also handy if you want a red and your companion wants a white, like the two shown here. Half bottles are also convenient for picnic outings. And, empty half bottles are great for storing leftover wine; just fill the half bottle as close to the top as you can, reseal it (easily done if the closure is a screw cap), and park it in the refrigerator.

I’m obviously a wine enthusiast, and with my wife will drink all or most of a full bottle of wine with dinner just about every night. However, you may enjoy less wine with your meals. If so, consider 375 mL half bottles. They are also handy if you want a red and your companion wants a white, like the two shown here. Half bottles are also convenient for picnic outings. And, empty half bottles are great for storing leftover wine; just fill the half bottle as close to the top as you can, reseal it (easily done if the closure is a screw cap), and park it in the refrigerator.

Saké is often called rice wine, but that is a misnomer. While it is an alcoholic beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered, heated, and placed in casks for maturing. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

Saké is often called rice wine, but that is a misnomer. While it is an alcoholic beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered, heated, and placed in casks for maturing. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.