Three decades ago, on my first visit to Napa valley, I stopped by Beringer for a tasting. I didn’t know much about Beringer at the time, mostly that they had a long history and made some well-regarded wines. Back then, tastings were free, but a friend had given me a tip to skip that and head upstairs to the Founders room, where you could sample Beringer’s best wines for $10. As a bonus, there was a crowd downstairs, but I had upstairs nearly to myself. I left that session with a life-long affinity and appreciation of what Cabernets from Napa could be like. (Today, the basic tasting is $45, and the high-end samplings are $125 or $150, depending on which way you go.)

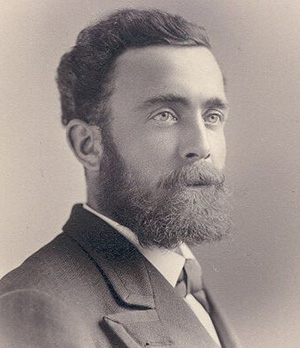

In 1868, Jacob Beringer, enticed by the opportunities of the new world, sailed from his home in Mainz, Germany, to New York. However, after hearing that the rocky hillside soil and fertile valley floor of Napa Valley resembled that of vineyards back home in Germany, Jacob made his way to California in 1869. He became cellar foreman for Charles Krug, one of the first commercial winemakers in Napa Valley. A few years later, in 1875, Jacob and his brother, Frederick, purchased 215 acres next door to Charles Krug in St. Helena for $14,500. This parcel of land, known as Los Hermanos (the brothers), became the heart of the Beringer estate.

Here, the brothers oversaw their first harvest and crush in 1876. With Jacob serving as winemaker and Frederick as financier, they made approximately 40,000 gallons of wine, or 18,000 cases, that first year. In order to house the fermentation tanks, the first two floors of the original winery were built, and Chinese workers began digging a 1,200-foot-long tunnel to store the wine for aging.

To make room for what is now known as the Rhine House, Beringer’s iconic building, Frederick had Jacob’s residence, the Hudson House, moved 200 feet north using horses and logs in 1883. Two years later, the brothers planted elm trees along Main Street in front of the winery, which now forms a verdant tunnel as the entrance to the estate. In 1967, Beringer Winery was named a State Historic Landmark for its significance to California’s history. In 1972, the Rhine House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

After Frederick died in 1901, and then Jacob’s passing in 1915, Jacob’s children, Charles and Bertha Beringer, took over ownership of the winery. While most wineries shut their doors at the beginning of Prohibition in 1920, Beringer continued to operate under a federal license that allowed them to produce sacramental wine for religious purposes, making them one of the few survivors of that dark time. A year after Prohibition ended in 1933, Beringer was the first winery to offer public tours, sparking wine tourism in Napa Valley. This was further expanded in 1939 when winemaker Fred Abruzzini distributed flyers and maps of area at the Golden Gate Exposition on San Francisco’s Treasure Island.

There have been winemaking advancements over the past 146 years, of course, several of which are still in place today. Beringer was one one of the first gravity-fed facilities, and among the first to operate using hand-dug caves and cellars. In 1977, Beringer began fermenting Chardonnay and Cabernet in French oak barrels. In 1989 the winery launched the first formal research and sensory evaluation program. Expanding vineyard sourcing to the Central Coast in 2012 allowed them to broaden the portfolio. And, they are the only winery to have both a red and a white wine simultaneously named #1 Wine of the Year by Wine Spectator magazine.

winemakers

Beringer winemakers have had an average tenure of almost 16 years per winemaker. In 1971, Myron Nightingale joined Beringer as the 5th winemaker. He developed a special French Sauternes-style wine, Nightingale, named after himself. After Ed Sbragia joined Nightingale as assistant winemaker, they launched the Private Reserve collection, using specifically selected Cabernet and Chardonnay grapes. Sbragia was promoted to winemaker in 1984. In 1997 Laurie Hook was named assistant winemaker, and in 2000 she became the 7th winemaker, with Sbragia staying on as Winemaker Emeritus. In 2015, Jacob Beringer’s great, great grandson, Mark Beringer, joined the team as Chief Winemaker, with Laurie Hook becoming Winemaker Emeritus. In 2021, after six years working with Mark, Ryan Rech took the reins as Chief Winemaker.

Laurie Hook oversaw the making of this wine. She began her career in the winemaking program at University of California at Davis in 1984. She then traveled to Australia to work at a small winery. After returning to work a harvest in Sonoma, Hook came to Beringer as an enologist in 1986, a job that allowed her to solidify the scientific side of her training.

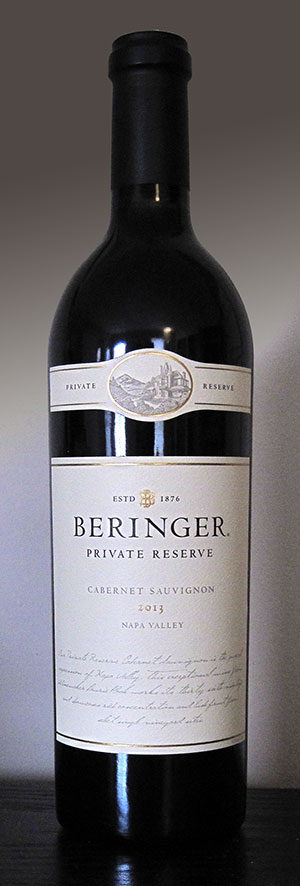

Beringer Private Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 2013

The first vintage of Beringer Private Reserve Cabernet was in 1977. Both the 1977 and 1978 were sourced solely from the Lemmon-Chabot vineyard. There was no PR Cabernet in 1979, the only year skipped so far, although Beringer claims that is always their prerogative. 1980 ended the run of single vineyard Private Reserve Cabernets. Since then, the wine has been a blend of the best lots from multiple vineyard sites.

Grapes were sourced from the Steinhauer (45%) and Bancroft Ranch (22%) vineyards, both on Howell Mountain, St. Helena Home vineyard (6%), and the rest from Calistoga and Mount Veeder. It is composed of 96% Cabernet Sauvignon 3% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot. A minimalist approach to winemaking has long defined this special blend. Each vineyard is vinified separately and monitored carefully from the moment the fruit comes into the winery at harvest. Tailored pump-over techniques are used for optimal extraction, and the wine is aged in hand-selected, custom-toasted barrels of 84% new French Nevers oak for 17 months before selection of the final blend.

It is an inky but completely transparent dark purple. There is a medium aroma of crème de cassis, dark fruits such as currant and plum, and a bit of alcohol, perhaps to be expected since the ABV is 15.2%. The fruit is moderately restrained compared to California Cabernet stereotypes, with flavors of blackberry, graphite, unsweetened chocolate, and spicy oak on a full body. When the bottle was opened, there was a good balance of acidity and tannins. Those tannins become rather more grippy an hour or so later, which was fine with me. It all wrapped up with a long and elegant finish.

Note: This selection is guilty of Bloated Bottle Syndrome, which I’m calling out for bottles that weigh more than the wine they contain. The web site of nearly every winery will usually include a mention of the operation’s dedication to “sustainability” and “stewardship.” Unfortunately, this often seems only to extend to the property itself. Many “premium” wines like this one come in heavier bottles to allegedly denote quality. This one weighs in at a hefty 880 grams. (As an example of a more typical bottle, Estancia Cabernet’s comes in at 494 grams.) That’s a lot of extra weight to be shipping around the country. By comparison, the wine inside, as always, only weighs 750 grams. Even sparkling wine bottles often weigh less than this one, and those are made to withstand high internal pressure. Unfortunately, this sort of “bottle-weight marketing” is becoming more common, especially at higher price points. But there are other ways to denote quality without weight: unusual label designs, foils, wax dipping, etc.

Plastic bottles have a lower environmental impact than glass, 20% to 40% less, in fact. And, bag-in-box packages are even less than plastic bottles. (Unfortunately, current bag technology will only keep unopened wine fresh for about a year, so they are only suitable for wines to be consumed upon release from the winery; that’s about 90% of all wine sold though.)

The carbon footprint of global winemaking and global wine consumption is nothing to scoff at. The latter, which requires cases of wine be shipped around the world, imprints a deep carbon footprint. Because wine is so region-specific, and only so many regions can create drinkable bottles, ground and air transportation is responsible for nearly all of the wine industry’s CO2 emissions.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/