Click here for tasting notes.

Louis Roederer Champagne Rosé 2016

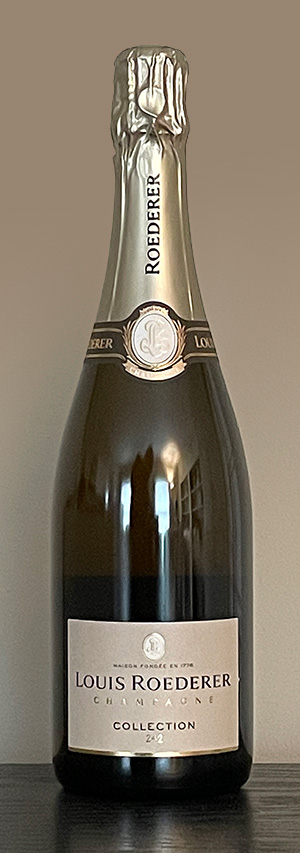

Louis Roederer [Road-ur-ur], a distinguished champagne producer situated in Reims, France, traces its origins back to 1776, when it began as Dubois Père & Fils. While its early days were marked by still wine production, the focus soon evolved to embrace the art of crafting fine champagnes. The business underwent a transformation under the stewardship of Louis Roederer in 1833 when he not only inherited but also renamed the company for himself. He boldly ventured into international markets, focusing particularly on Russia. This endeavor gained him immense recognition, including from Tsar Nicolas II, who appointed Louis Roederer as the official wine provider to the Imperial Court of Russia.

Created in 1876, the wine made for Nicolas’ grandfather, Alexander II, was the first Cuvée de Prestige (Prestige Cuvée) of Champagne and is called Cristal, referring to the unusual clear glass of the bottle. The Tsar had pointed out to his sommelier that the design of a standard champagne bottle made the beautiful color and effervescence of champagne invisible to the eye. He therefore instructed Roederer that his personal cuvée be served in bottles made of transparent crystal glass with a flat bottom (allegedly to foil the insertion of explosives in the indentation by would-be assassins) to remedy this defect. Thus was Cristal born, and the first notion of a premium cuvée. For more than a century, the appearance of the patented Cristal bottle has remained unchanged. After the fall of the Russian monarchy in 1917, Roederer decided to continue producing Cristal and to market it internationally, and it remains one of the world’s most sought-after champagnes in the world.