Note: This isn’t really a blog post, but rather a long-form essay.

If you would prefer a printed copy for reading, the PDF is here.

For an edited “Reader’s Digest” version of this essay that is about half as long, the PDF is here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Spanish Colonization

The Spanish Mission System

The Establishment of Missions throughout California

Fray Juniper Serra and His Missions

The Exploitation of Native Americans

Southern and Central California As The First Wine Region

Missions Founded in San Luis Obispo County

Los Angeles as a Wine Making Center

The Gold Rush and the movement of Wine Production North

Sonoma Valley Pioneers

Napa Valley Pioneers

Exporting California Wine in the Formative Years of Napa Valley

The Early Twentieth Century

The California Wine Association

The Scourge of Prohibition

Highlights of the Modern California Wine Industry

Father of the Modern Era: Andre Tchelistcheff

The Emergence of Single Vineyard Wines

The Judgment of Paris

The Mondavi Family

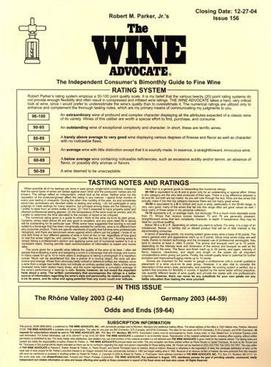

The Elephant in the Room: Robert Parker

The Amazing 1990s

California Cult Wines

Jean Phillips and Screaming Eagle

Bill Harlan

David Abreu

Andy Beckstoffer

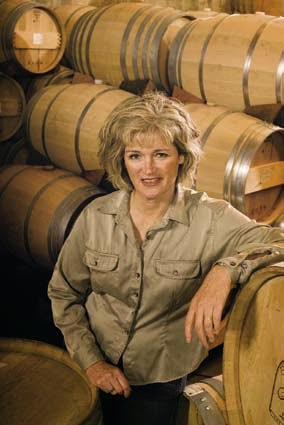

Helen Turley

Contemporary Grapes and Wines

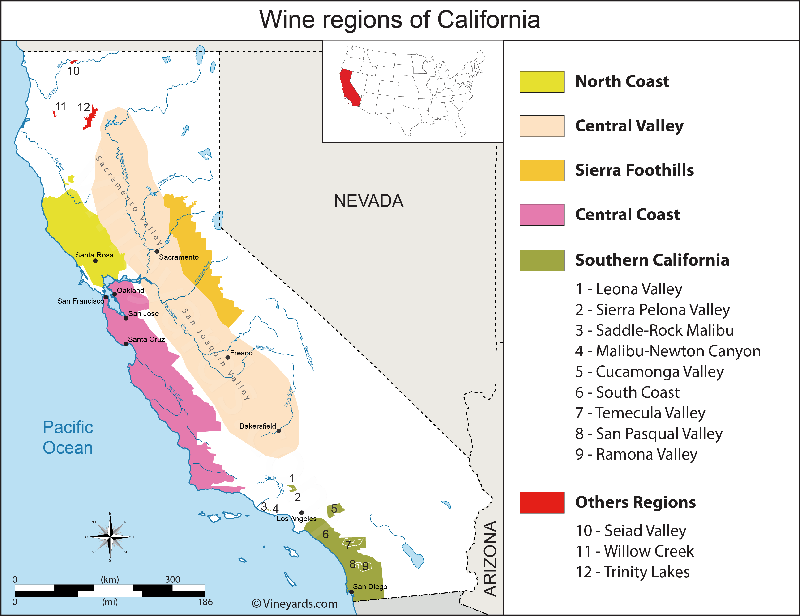

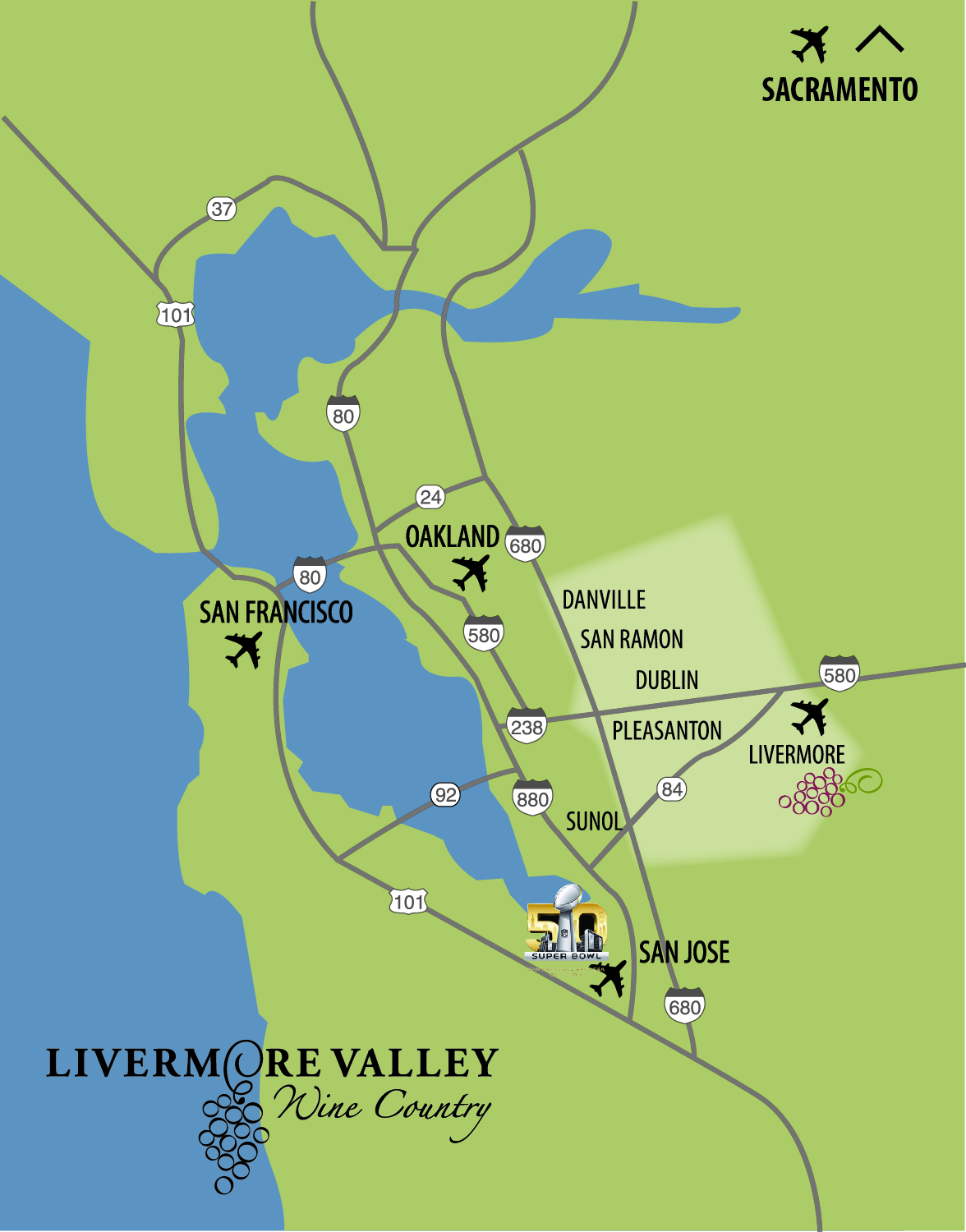

California Wine Regions

American Viticultural Areas

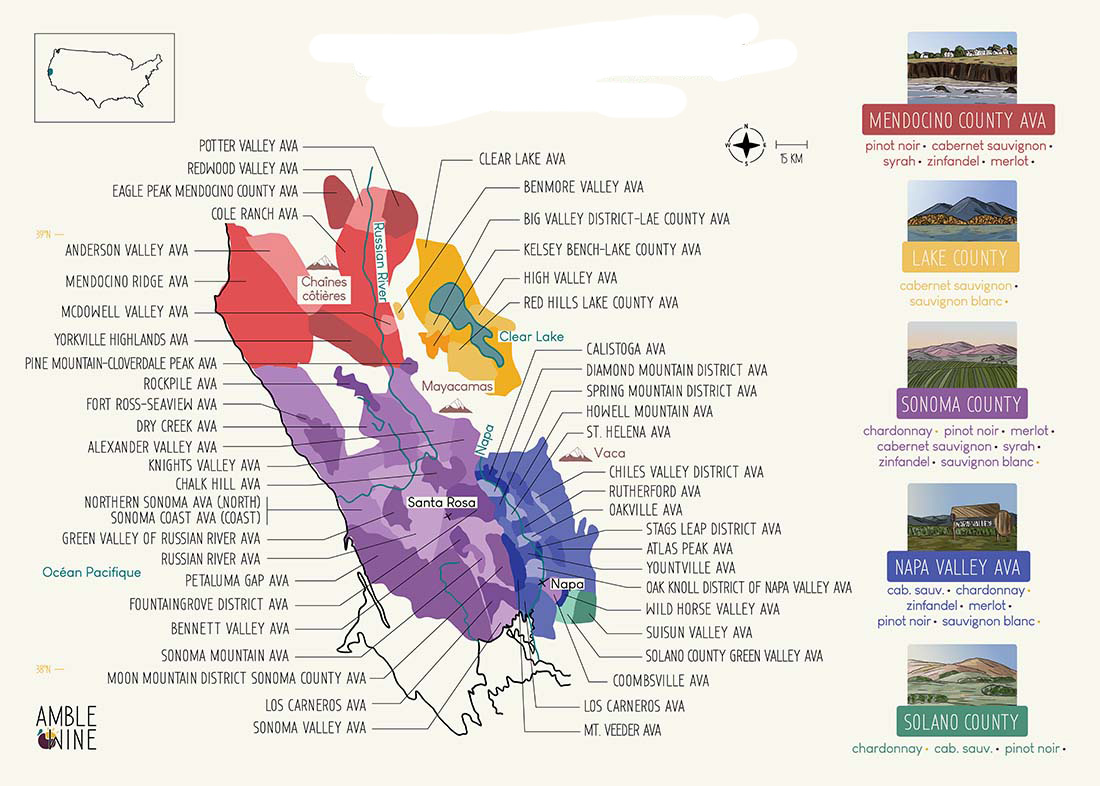

The North Coast

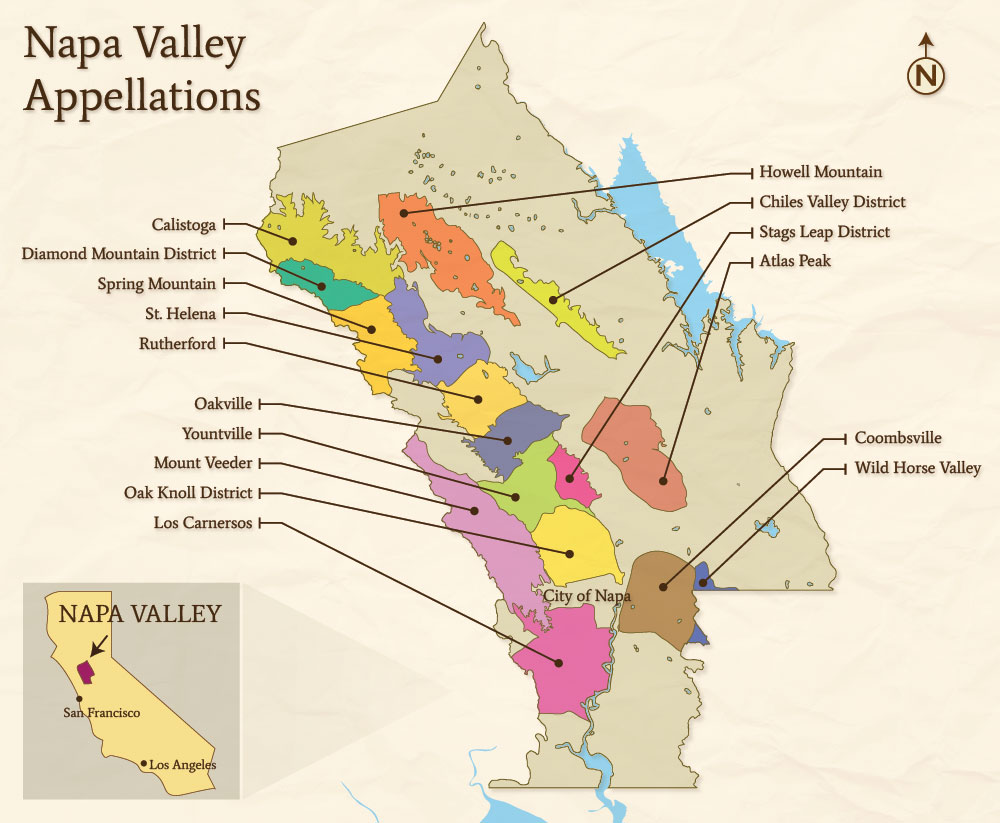

Napa Valley

Sonoma Valley

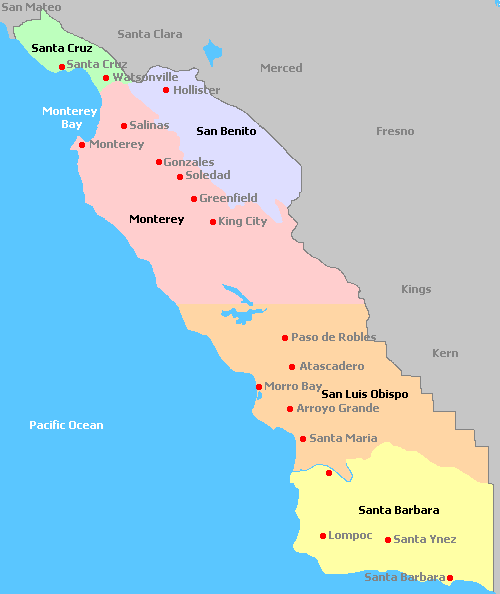

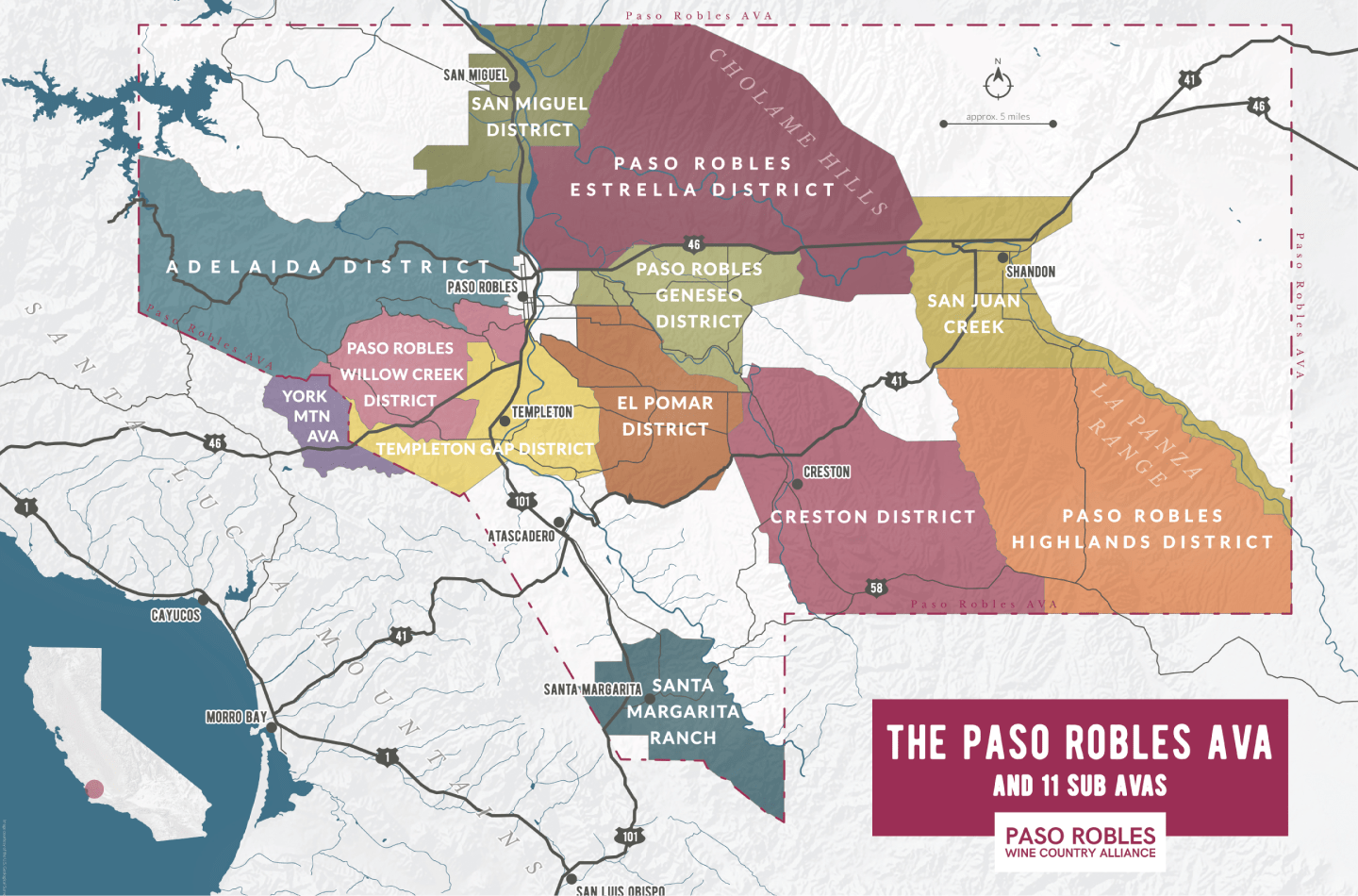

The Central Coast

A Renaissance in Southern California

The Temecula Valley

Notable Ethic Groups

Native Americans and Mexican-Californios

Chinese-Americans

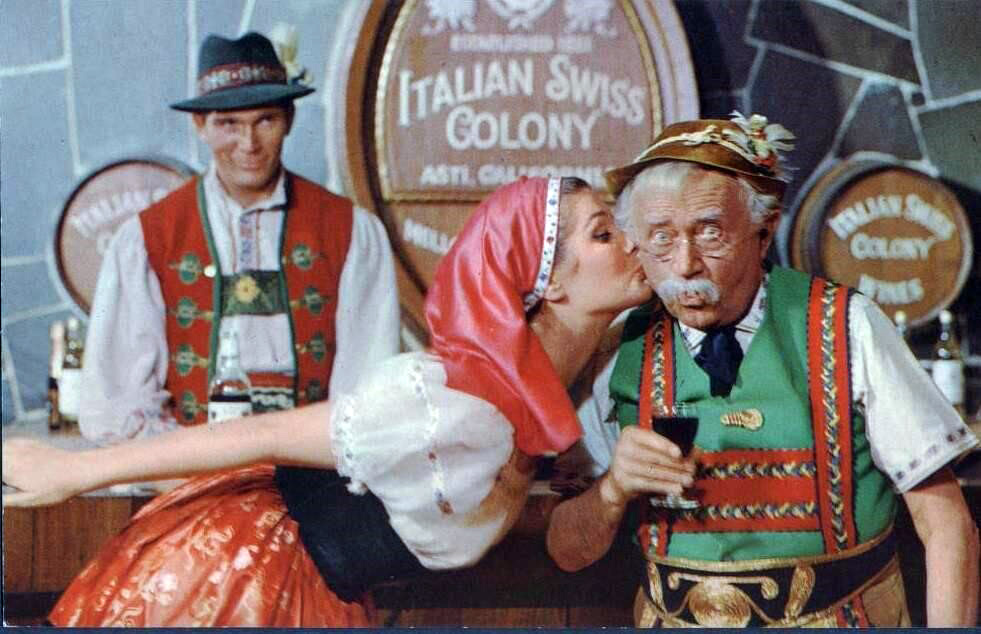

Italian-Americans

Mexican-Americans

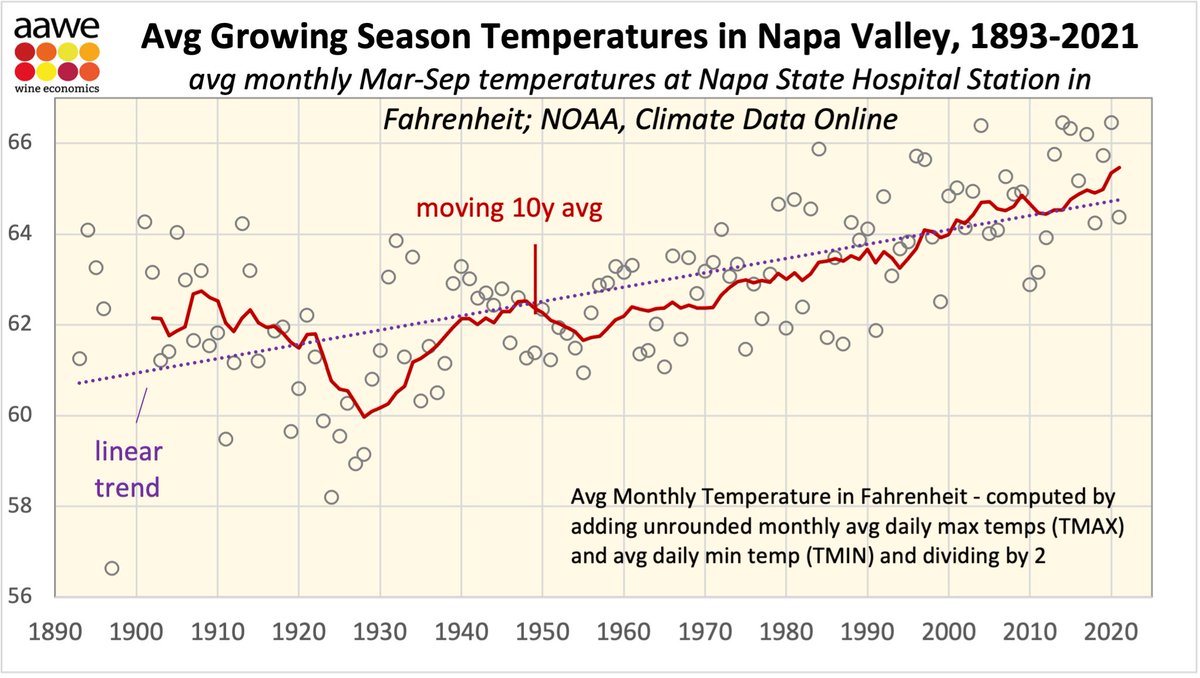

Challenges and Opportunities in the California Wine Industry

Introduction

California’s wine history is a saga that intertwines the tales of immigrant dreams, technological innovation, ecological adaptation, and cultural transformation. From humble beginnings in the Spanish Missions to the globally recognized wine powerhouse it is today, California’s wine industry has undergone remarkable evolution. This narrative spans centuries, traversing through triumphs and setbacks, capturing the essence of California’s terroir and the indomitable spirit of its winemakers.

The history of California wine as we know it began with the arrival of Spanish missionaries in the late 18th century. Seeking to establish footholds in the New World, the Franciscan friars planted vineyards to supply sacramental wine for religious rites. Among the first vineyards were those at Mission San Juan Capistrano and Mission San Diego, where varieties like Mission grapes were cultivated. These plantings marked the birth of viticulture in California and set the stage for future expansion.

Following Mexico’s independence from Spain, secularization of the missions led to the distribution of their lands among Mexican ranchers. Many of these ranchos continued the tradition of wine production, expanding vineyard acreage and experimenting with new grape varieties. The Padrone system, where laborers were paid in wine, further incentivized viticultural growth.

The discovery of gold in California triggered a population boom, transforming the region into a bustling hub of opportunity. As fortune seekers flooded the state, demand for wine skyrocketed, leading to a surge in vineyard plantings. However, quality often took a backseat to quantity during this period, with many hastily established vineyards producing inferior wines.

In the wake of the Gold Rush, California’s wine industry underwent a renaissance fueled by technological advancements and immigrant expertise. European immigrants, particularly those from winegrowing regions such as Italy, France, and Germany, brought valuable knowledge and skills to the burgeoning industry. Pioneers like Agoston Haraszthy, often dubbed the “Father of California Viticulture,” played pivotal roles in elevating winemaking standards and promoting quality over quantity.

Despite the industry’s progress, it faced significant challenges in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The arrival of the Phylloxera louse devastated vineyards across California, necessitating widespread replanting on resistant rootstocks. Moreover, the enactment of Prohibition in 1920 dealt a severe blow to the wine industry, forcing many wineries to shut down or transition to alternative products.

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 heralded a new era of growth and innovation for California wine. Wineries that had survived the dry years rebounded, while new ventures emerged, capitalizing on increasing consumer interest in wine. The establishment of American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) and the founding of institutions like the University of California Davis, further propelled the industry forward, fostering research and education in viticulture and oenology.

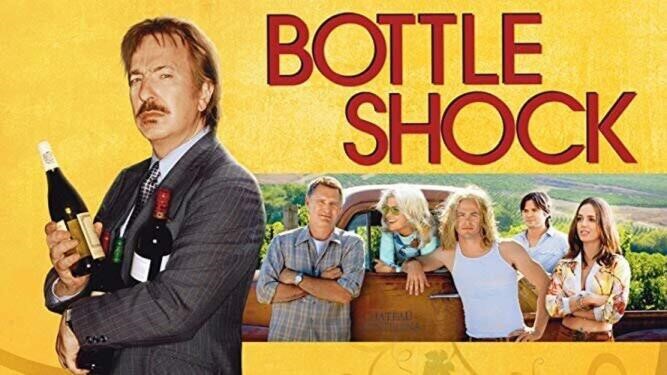

The turning point for California wine came in 1976 with the historic “Judgment of Paris” blind tasting. In a shocking upset, California wines outperformed their French counterparts, garnering top honors in both the red and white categories. This watershed moment not only shattered the perception of California as a mere producer of jug wines but also catapulted its wines onto the global stage, earning respect and acclaim from oenophiles worldwide.

California’s wine industry continued to innovate in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, embracing advancements in viticulture, winemaking techniques, and sustainability practices. From precision agriculture and mechanization to organic and biodynamic farming, wineries across the state adopted measures to enhance quality while minimizing environmental impact. Additionally, the adoption of state-of-the-art winemaking equipment and practices further refined the quality and consistency of California wines.

Alongside established producers, a wave of boutique and cult wineries emerged, challenging traditional notions of wine production and consumption. These small-scale operations focused on limited-production, handcrafted wines, often showcasing unique grape varieties or terroirs. The cult following garnered by some of these wineries propelled them to international acclaim, underscoring the diversity and dynamism of California’s wine scene.

Despite its success, California’s wine industry faces a myriad of challenges in the 21st century, including climate change, water scarcity, labor shortages, and market saturation. Wineries are increasingly investing in sustainable practices, drought-resistant grape varieties, and alternative irrigation methods to mitigate environmental pressures. Moreover, evolving consumer preferences and the rise of e-commerce are reshaping the landscape of wine marketing and distribution.

Spanish Colonization

The Spanish Mission System: A Model of Sustainable Development in Alta California

The colonization of Alta (or Upper, as opposed to Baja, or Lower) California by the Spanish during the 18th and 19th centuries was a transformative era that laid the groundwork for the region’s development and agricultural prosperity. (This vast territory included all of the U.S. states of California, Nevada, and Utah, and parts of Arizona, Wyoming, and Colorado.) At the core of this colonization effort were the Missions, which served as vibrant centers for community life and economic activity. Contrary to modern misconceptions, these Missions were expansive complexes encompassing diverse structures dedicated to agriculture, industry, healthcare, hospitality, and administration, functioning as self-sustaining communities that catered to the needs of their inhabitants and facilitated trade with neighboring settlements.

Agriculture emerged as a cornerstone of the Mission system, with each Mission serving as an agricultural hub where crops were cultivated and livestock raised. The Spanish missionaries, known as friars, leveraged their expertise in soil, climate, and weather patterns to identify suitable crops and animals for cultivation, conducting meticulous research and experimentation to enhance agricultural productivity. Their observations and trials in diverse microclimates laid the groundwork for California’s rich agricultural heritage, setting the stage for the state’s prominence as a leading producer of various crops, not the least of which are wine grapes.

Furthermore, the Missions played a pivotal role in transportation planning, with trails and roads being developed to connect distant settlements and facilitate travel for travelers, soldiers, and friars. These routes not only served as arteries for communication and mobility but also enabled the exchange of goods and resources between Missions and trading markets along the Pacific Coast, fostering economic growth and regional connectivity.

Water management emerged as another critical aspect of land use planning in Alta California, with the Missions relying on a sophisticated network of rivers, creeks, springs, aqueducts, and dams to ensure a dependable water supply for agricultural activities and other purposes. Despite facing challenges posed by California’s variable climate and limited water resources, the friars implemented innovative techniques to control and transport water, demonstrating foresight in addressing enduring environmental challenges.

The success of the friars in agricultural endeavors can be attributed to their familiarity with Mediterranean climates, especially that of Spain, which facilitated the cultivation of crops suited to the region’s conditions. Harnessing the influence of Pacific Ocean fog and cool breezes, the friars strategically located Missions close to the coast, optimizing agricultural productivity and mitigating environmental risks.

Structured with a business mindset, agriculture under the Franciscans’ stewardship operated with painstaking planning and specific skills, aimed at generating surplus produce for trade and barter with merchants and sea captains to bolster economic security. Through meticulous experimentation and record-keeping, the friars imported a wide variety of plants and trees from Europe, adapting them to Alta California’s soils and climates, and disseminating agricultural knowledge to local farmers.

Vineyards, orchards, gardens, and ranchos became integral components of the Mission landscape, demonstrating the careful planning and organization that underpinned agricultural activities. The Missions served as hubs for teaching agricultural skills to local inhabitants, predominantly Native Americans, fostering economic self-sufficiency and community development.

The Establishment Of Missions Throughout California

The story of wine in California begins with the story of the Spanish in California. In 1518, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés sailed with his army from Cuba to conquer Mexico. He discovered Baja (Lower) California on the Pacific Coast, and claimed it for Spain. He also decreed that each settler in Mexico and Baja had to plant 1,000 vines per 100 inhabitants on the land, establishing viticulture in the region.

On the 28th of September in 1542, Portugese explorer Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo landed with his expedition at San Diego Bay. It was the first time that a European expedition had reached California. In the weeks that followed, his small armada of three ships explored much of the coast as far north as the current San Francisco.

However, because of how geographically remote California was from the main centers of Spanish settlements in Central Mexico, the Spanish did not establish colonies there for over 220 years.

King Charles III, who reigned from 1759 to 1788, was determined to expand the Spanish empire. He launched new voyages and land expeditions to survey the Pacific Coast, as the efforts and records of the early explorers had been lost and forgotten over the previous two centuries. Charles III sent military troops and Franciscan friars to Alta California to colonize the territory, introduce Spanish culture, and convert its inhabitants to Catholicism by establishing settlements, now known as Missions.

José de Gálvez was a Spanish lawyer and Inspector General for the Vice Royalty of New Spain, which included all of Spanish North America. He exercised sweeping powers, and he is credited with developing the idea of building Missions to control Alta California. Gálvez selected Fray (Friar) Junípero Serra as his chief missionary and President of the Missions.

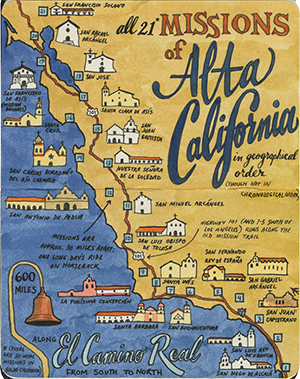

In all, 21 Missions were established south to north from San Diego to Sonoma along the Camino Real, settlements such as San Diego, San Juan Capistrano, Ventura, and San Francisco. Each Spanish Mission was a religious and cultural center built to spread both Catholicism and Spanish culture to the local inhabitants. Spain wanted those who lived in Alta California to become citizens of the “New Spain.” But the Mission was also an important economic structure. Each Mission was designed to be self-supporting within five years of its founding.

After the construction of Mission churches, the Franciscans’ key priority was to establish formal agricultural cultivation. First, instructing Indians in the agricultural arts was part of the process of Hispanicization, which furthered the Spanish conquest and colonization. Second, doing so would secure a regular supply of food that could sustain the Missions. Still, scarcity plagued the Missions throughout the 1770s. In his frequent letters to government officials and church leaders in Mexico City, Junípero Serra frequently pleaded for materials, especially religious and liturgical goods to furnish the new Missions and allow for further expansion. Without fundamental religious items—such as candles, crucifixes, and eucharistic hosts—the Franciscans could not carry out their primary objective, to convert and baptize Indian neophytes. These shortages included sacramental wine, which was of paramount importance to the Franciscans. They could not say the Mass without access to a regular supply of wine, which had to be shipped from Mexico; this threatened to hamper their evangelization. To remedy these shortages, the Franciscans directed Mission Indians to begin planting the region’s first vineyards about 1770 at San Juan Capistrano and San Gabriel, with the first Mission wines produced in the mid-1780s.

Cuttings from the original vines brought to Mexico by Cortés gradually spread from Mexico to the area we know today as New Mexico in 1620, and ultimately to Alta California. The wine made from these vines was used for religious sacraments as well as for daily life. The vine cuttings were the descendant of the “common black grape” (as it was known), and became known in the New World as the Mission grape, since that was where they were planted, and the missionaries were unconcerned with what varietal they were. Indeed, the vines were a so-called “field blend,” where numerous unknown varieties grow together. The primary grape has been identified, five centuries later, as Listán Prieto, a red grape believed to have originated in the Castilla / La Mancha region of Spain.

The success of Mission vineyards relied on the migration of plants, ideas, and, most significantly, of people. The Franciscans relied heavily on the expertise and labor of Indians from Baja California, who migrated north with the Franciscans. These campesinos served as liaisons between the Franciscans and local Indians, teaching and supervising their labor in constructing Mission buildings and in clearing fields, planting, irrigating, and harvesting crops.

During the Franciscans’ fifty-year tenure in Alta California, winegrowing remained a largely non-commercial venture. Although there was limited trade of wine between the Missions, presidios, and pueblos of Alta California, and evidence of illicit alcohol sales (particularly to Indians, who were prohibited by law from enjoying the fruits of their labors outside of the Mass), Spanish colonial laws restricted the wine trade. Winegrowing took a commercial turn following a series of political events that dramatically altered California. First, Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1822 opened California to foreign traders. Second, the Mexican government passed the Colonization Act of 1824 to entice colonists to its northwestern frontier. Finally, in 1833 the secularization of the Missions opened up vast tracts of land originally intended for Indians, but which ended up in the hands of large-scale land owners.

Fray Junipero Serra and His Missions

The California wine industry is comparatively very young. It only emerged around 250 years ago along the west coast. Much of its origins can be traced to one man, Fray Junipero Serra, who was also referred to as the Apostle of California.

Serra is considered the ‘Father of California Wine,’ as wine had not been produced in California before his arrival, and he and his followers truly set the state’s industry in motion. Originally, he began his Missionary work in Mexico in the mid 18th century. However, in 1769 Serra set out from Baja California and headed north. On the 16th of July 1769, he and his fellow travelers arrived at the site of what is now the city of San Diego. Here, they established the first of their religious Missions in California, effectively a settlement run by the Franciscans. It would also become California’s first permanently settled Spanish and European town.

Over the next thirteen years, Serra and an ever-growing number of fellow missionaries established further religious Missions up and down the western coast of California. The timeline of the nine Missions Fray Serra founded is: Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá on the south bank of the San Diego River in what is now San Diego Old Town in 1769, Mission Carmel in Monterey which became his headquarters in 1770, Mission San Antonio and Mission San Gabriel in 1771, Mission San Luis Obispo in 1772, Missions Delores in San Francisco and San Juan Capistrano in 1776, Mission Santa Clara in 1777 and Mission San Buenaventura in 1782 in what is now Ventura.

Serra was charged with selecting the sites of each Mission, making certain there were sources of water, lands for planting grains and cereals, vineyards, orchards, and grazing lands for horses, cattle, and sheep. He selected the friars he felt could administer and develop the plans for each Mission site, which included planning for multiple buildings. He consulted with them and lobbied on their behalf to obtain the supplies needed.

He traveled thousands of miles between San Diego to Carmel during the years he spent founding the Missions. Most of the Missions were within 35 miles of the Pacific Ocean so they could receive supplies and send shipments to other Missions, presidios, and pueblos by boat.

The Mission system was an extraordinary experiment in colonization. It was successful in bringing Spanish culture, architecture, building techniques, art, music, religion, water management, and agricultural practices (especially viticulture) to California, particularly on the Central Coast.

Each of the nine Missions Serra founded was established at a specific location taken in the name of the king of Spain and marked by a religious ceremony. The Missions supported the declaration of the province of New Spain in Alta California, and were an expansion of the empire of Spain by establishing relations with the natives of western and southern California and attempting to convert them to Roman Catholicism by preaching and establishing churches and schools. It is estimated that there were over 300,000 natives in California by the mid-18th century, people such as the Chumash, Luiseno, Cahuilla, and Cupeno. Thus, as Serra and his fellow Franciscans would have perceived, there were many souls to be saved.

The Exploitation Of Native Americans

As Roman Catholicism is centered on the celebration of the Mass to recreate the Last Supper, this involves wine – and with nine Missions along the coast of California preaching to tens of thousands of natives, a lot of wine was soon needed.

As Spanish settlements in California had been non-existent prior to Serra’s arrival, and the natives did not have an indigenous wine industry, Serra and his followers initially imported large amounts of wine from Spanish settlements further to the south in Baja California. However, given the effort and expense involved in doing so, it wasn’t long before Serra and his fellow Franciscans elected to begin making their own wine.

Indeed, Serra had predicted the need for wine-making facilities even before arriving in Upper California. When he and his party arrived in San Diego to establish their first Mission in 1769, they brought cuttings from vineyards in Baja California. And soon, they began planting them to establish California’s first vineyards.

Serendipitously, Serra and his acolytes had actually established their first vineyards in one of California’s most fruitful parts. Later, when they attempted to plant vines near San Francisco, the combination of the cooler climate and the sea air proved less advantageous than the previously warmer climes of southwestern California.

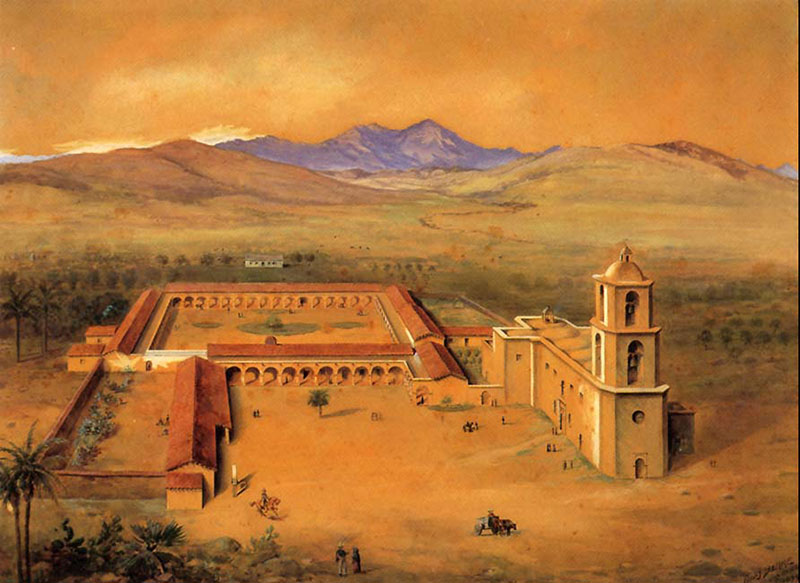

In the years that followed, the level of wine production by the Franciscans across western and southern California expanded as the number of missionaries and their acolytes at the nine Missions increased, and the roughly 20,000 Native Americans associated with them. Wine production flourished in particular at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel near modern-day Los Angeles, which eventually transformed into the center of the Californian wine industry for decades to come.

At its core, winegrowing was established for the sole purpose of furthering the conquest and colonization of Alta California. Wine was not simply a beverage, but rather was a tool of conquest. The Franciscans used viticulture to Hispanicize California Indians, and they used wine produced from Mission grapes to convert them to Christianity. Indian laborers planted vineyards, brought in the harvest, and crushed the grapes. In doing so, Mission Indians literally sowed the seeds of viticulture and wine in California. Because the Franciscans used agricultural labor to further conquest, they often eschewed modern farming methods that had the potential to make vineyard labor easier on Indian farmworkers. For example, they implemented recommendations from an antiquated Spanish agricultural manual, which meant that Indians pruned grape vines using the “head-pruning” method, essentially training vines to grow into low bushes instead of along wires, trellises, and posts. This did lessen the labor initially required to plant vineyards, but the bending required to prune and harvest the grapes was especially strenuous. This was in keeping with labor across the Missions, which consisted of backbreaking stoop labor and other farm work that was not mechanized until the 1820s, long after mechanized cultivation reached other regions of North America.

The Native Americans were lured to the Missions by talk of Christianity, or were seeking shelter during a time of environmental change and disease. Upon Baptism, though, the Spanish controlled their lives and forced them to work the fields.

In The Grapes of Conquest: Race, Labor, and the Industrialization of California Wine, 1769-1920, Julia Ornelas-Higdon wrote, “Wine was really a tool of conquest for the Spanish,” noting that Indigenous Californians were prohibited from drinking wine outside of the confines of the Catholic Mass. Even ownership of wine-making tools was criminalized. “California natives are the ones who planted, pruned, harvested the grapes, and did all of that work,” said Ornelas-Higdon. “Yet the irony is that they had very limited access to the literal fruits of their labors.”

One of the first acts of legislation passed by the newfound state of California, in 1850, was the Indian Indenture Act. The law forbade Native Americans from voting, and allowed them to be arrested on the spot for not working or for appearing drunk. Native Americans would often be arrested on weekends. When they were released from jail, their labor was sold to the highest bidder, often a grape farmer. “At the end of the week, the farmers would pay two thirds of the fine to the city and the rest to the Indian worker—in high-alcohol aguardiente (a distilled licorice-flavored spirit), ensuring the cycle would be repeated. That cruel cycle lasted until 1862, when the California Legislature repealed the act.

Serra and his fellow Franciscans have been accused of severe mistreatment of the natives of California. Studies have highlighted how the thousands of natives who were involved in the Franciscan Missions in the 1770s were subjected to corporal punishment.

>Some of this is partially explained by the severe methods employed by the Franciscans in the 18th century and Serra’s own personal habits. For instance, he practiced self-flagellation, whereby he whipped himself as a way of atoning for his sins. Regardless, the brutal treatment of the natives of Alta California casts a dark shadow over California’s early wine industry, much of which was initiated through the forced labor of local indigenous people. For his role in converting the natives of California, Junipero Serra was canonized as a saint in 2015, but over the opposition of Native American groups.

Southern and Central California As The First Wine Region

After the founding of Mission San Diego de Alcalá_ in 1769, the Missions advanced northward. Vine cuttings were planted at each of the new Missions, with some Mission sites more successful than others. Among the most successful of the Missions was Mission San Gabriel, just east of Los Angeles, whose wines were generally regarded as the finest of all the Mission wines. Production of wine there grew to 50,000 gallons a year in a winery that was 14 by 20 feet in size. The Mission grape also prospered at Mission San Juan Capistrano where it was first planted, and in the vineyards of Mission San Luis Obispo which became the second largest producer of wine in Alta California.

By the early 19th century the California wine industry was concentrated in Southern California, with a number of successful wineries being established in what is today downtown Los Angeles, San Gabriel Valley, and the Cucamonga Valley. During the 1800s, Southern California provided most of the wine produced in the state.

Official records indicate there were four wines made from the one Mission grape varietal. The first was a sweet white wine made by fermenting the wine without the skins. Two red wines were made both as dry or sweet by fermenting the juice and skins together. A sweet wine was made by adding brandy to fortify it.

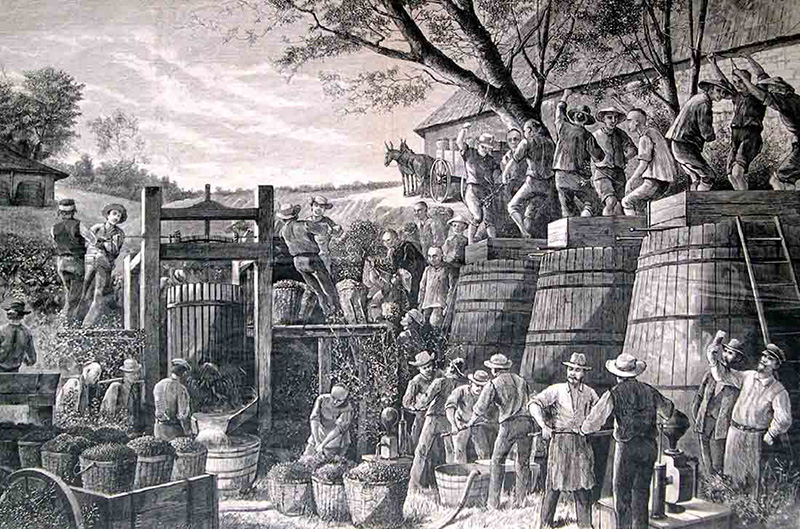

The Indians would have harvested the grapes into woven baskets. There were probably no knives available so bunches would have been pulled off the vines. Mission grape bunches have brittle stems so the process should have been relatively easy to do.

At some Missions, the wineries were built with a sloping floor. The grapes were placed on the floor and Indians would dance on them to crush the fruit. The juice drained into a small well in the floor and was scooped into cowhide bags. In the early years, there were no barrels, so new bags were made each year from cowhides coated with pitch and sewn up with the hair side in, very similar to a Spanish bota bag. These bags were flexible during the fermentation process and could be delivered directly to the consumer. Eventually wooden barrels were introduced to store wine. Many of these barrels had contained supplies shipped from Spain to Alta California.

The most important contribution of the Mission grape was to prove that grapes could be grown in the coastal regions of California. Mission grape vines continued to flourish well into the 1880s. The Mission wines produced by the first commercial winemaker, Pierre Hypolite Dallidet, in San Luis Obispo County, were highly acclaimed for their quality and were sold throughout California. The Mission grape is still thriving in San Luis Obispo County. Some old vines grow wild and are standing over six feet tall. Others trail out along the ground or on fences. Even today, new Mission vines are being planted in local vineyards as part of a field blend.

Missions Founded in San Luis Obispo County

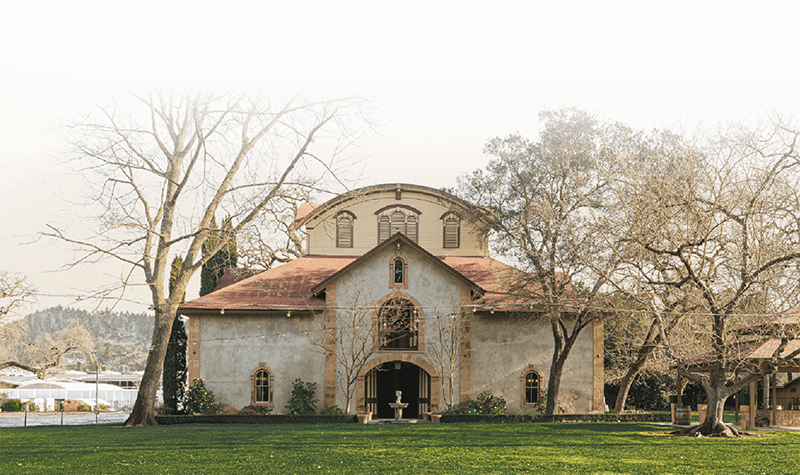

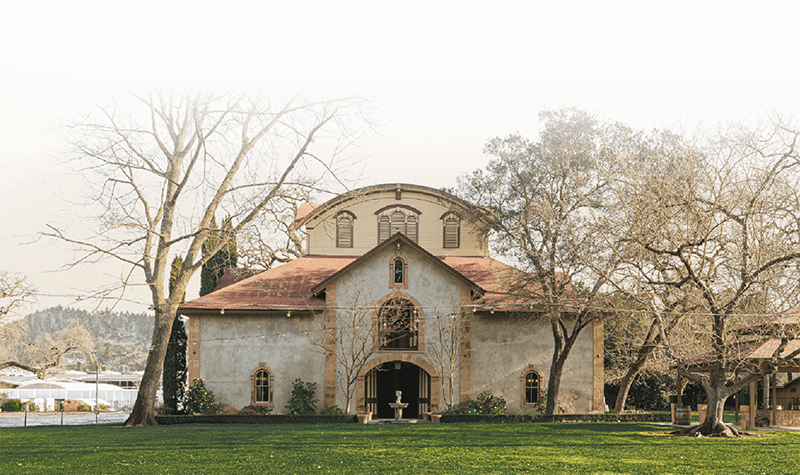

Photo: Courtesy Yelp/John L.

The Mission of San Luis Obispo de Tolosa was founded on September 1 in 1772. Fray Serra hung a bell in a tree to designate the location and said Mass for the soldiers and local inhabitants who attended the ceremony. He named the Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa for St. Louis, Bishop of Toulouse, France. St. Louis became a Bishop at age 23; he was brought up and revered by Franciscans. Fray Serra also was aware of the large bear population in the Los Osos Valley which would provide food for the friars and workers at the Mission San Luis Obispo and Mission San Antonio de Padua for several years before cattle ranching and crops were established.

The building of the Mission infrastructure was a lengthy process, often stretching over 30 years, but after many fires and other obstacles, Mission San Luis Obispo was finally completed in 1804. The Mission population reached its peak at 832 members.

There were two ranchos associated with Mission San Luis Obispo. The first was Santa Margarita de Cortona which became the principal source of growing wheat and storing the crop for the Mission. At Santa Margarita de Cortona the friars had an impressive building constructed from local stone with long corridors and arched doorways. There were multiple rooms for workers and for the storage of grain. There was a small chapel and a place for travelers to spend the night.

The second rancho was San Miguelito where corn and beans were grown and harvested. The ruins were located a few miles inland from the town of Avila and documented in 1934 by Edith Webb, although they no longer exist.

In 1845 the Mission was sold and the title transferred to three buyers, including Captain John Wilson, who paid a total of $510. In 1859 the United States returned the Mission to the Catholic Bishop in Monterey. It has remained a Catholic parish serving the area to the present day. The restoration of the building began in 1933.

Photo Courtesy of Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library

In 1797 Mission San Miguel Arcangel was founded 40 miles north of San Luis Obispo. It was the 16th of the 21 Missions. Both Missions had extensive lands and specialized in animal breeding. As usual, the vineyards were planted with Mission grape vines and tended by the friars. In 1822, after Mexico declared their independence from Spain and took possession of Alta California, the civil government took jurisdiction of the Mission properties.

The Indians subsequently left the Mission San Miguel and the Mission became impoverished. The Mission properties were then sold to Petronillo Rios and William Reed in 1846. The Reed family was brutally murdered there in 1848. For the next ten years the buildings were rented to a variety of owners who operated a saloon, a dance hall, storage facilities, and occupied the barns and living quarters. In 1859 the Mission was returned to the Catholic Church. In 1929 it returned to the control of the Franciscan fathers.

Los Angeles as a Wine Making Center

Before Napa and Sonoma counties became synonymous with California wine, the epicenter of wine production in the state was Los Angeles, which by the mid-1850s had earned the nickname of the “City of Vines.”

El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Ángeles, meaning the Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels, was established as the second Spanish civilian town in California in 1781. Five years later, the first vine cuttings were brought here from Mission San Gabriel Arcángel.

Mexican independence from Spanish rule in 1821 eventually led to the secularization of California’s Missions. The lands were broken up, and the property sold or granted to private citizens, who in turn developed ranchos, many of which became centers of wine production. According to historian Thomas Pinney’s The City of Vines: A History of Wine in Los Angeles, major wine-producing ranchos during the first half of the 19th century included Rancho Paso de Bartolo Viejo, which covered present-day Montebello, Whittier, and Pico Rivera, and Henry “Don Enrique” Dalton’s Rancho Azusa in present-day Azusa, Arcadia, Monrovia, Irwindale and Baldwin Park.

Photo: lastreetnames.com

Under Mexican rule, more European immigrants began to settle in California, including Frenchman Jean-Louis Vignes (downtown L.A.’s Vignes Street is named after him). While his previous ventures in France and the Sandwich Islands had failed, in California he found success. His one hundred acre El Aliso vineyard, as well as a winery and brandy distillery, were situated near the present-day location of downtown’s Union Station, and began the commercial wine industry in Southern California in 1834. He renamed himself Don Luis Vignes to assimilate into Mexican-Californio culture. He likely produced his first vintage in 1837; by the early 1840s, he was shipping his wines across California.

Plentiful lands were available on which newcomers could plant vineyards, as were markets to trade in wines and aguardiente. The vineyard owners and vintners driving this commercial turn included Mexican-Californios of the elite ranchero class and immigrants from Europe and the United States. In addition to their work as cattle ranchers, Californios Tomás Yorba and his wife Vicenta Sepúlveda Yorba produced wine and aguardiente from their vineyards at Rancho La Sierra. They traded their ranch goods, including hides, tallow, wine, and aguardiente, with Americans like William Heath Davis, a merchant and trader in Alta California who helped to establish “New Town” in what is now downtown San Diego.

The Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848 erupted as a result of a dispute over where the border between the two countries would lie in what is now Texas. The US favored the Rio Grande as the border, but the Mexican government argued it should lie at the Nueces River farther to the northeast. In the two-year conflict which ensued, the United States achieved a total military victory, advancing into Mexico and taking Mexico City itself.

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo saw Mexico cede an enormous expanse of territory to the US, stretching through the modern-day states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California. One of the often-ignored benefits this conferred to the United States is that the US acquired total control of the nascent California wine industry, which had been in development since the 1770s and which had begun to expand significantly following the war as American settlements out west exploded from the late 1840s onwards.

In the decades that followed, Los Angeles became the main urban center of Alta California, first on the back of its many cattle ranches and then during the Californian gold rush of the mid-19th century. Simultaneously, it grew into one of the main markets for California wine.

The wine industry evolved yet again between the 1850s and 1880s. Scholars have demonstrated how American legal and economic systems, the racial exclusion of former Mexican citizens, and violence all functioned to reorganize the power and wealth in California, ultimately dispossessing Mexican-Californios of their land and property rights. A new influx of Euro-American immigrant growers and winemakers were part of this group of new landowners that emerged in the decades following the Mexican-American War. They further commercialized and professionalized the industry by organizing trade groups and lobbying for government assistance. As they did so, these American newcomers started to shift the Southern California wine industry towards Euro-centricity and away from its previous mooring in Spanish and Mexican California.

Beginning in the 1860s, German immigrants emerged as a group of influential winegrowers in the Los Angeles area, which continued as the state’s hub of winegrowing. In 1854, German musicians John Frohling and Charles Kohler left San Francisco to become winegrowers in Anaheim. There, they purchased a vineyard and founded Kohler & Frohling Winery. By 1858, their wines were earning prizes at state agricultural fairs.

Photo: solanocanyon.org

The winery was so successful that the firm collaborated with George Hansen, a Los Angeles surveyor, to establish a vineyard colony, the Los Angeles Vineyard Society, which could sell grapes to their winery and allow for increased production. The company purchased land along the Santa Ana River, planted vineyards, and built the town of Anaheim. Within ten years, Anaheim’s winegrowers claimed that their vineyards were producing six hundred thousand gallons of wine annually; although this was likely an overestimation, Anaheim’s growers were recognized among the most productive in the state.

In 1859, the Los Angeles wine industry was given an added boost when the city agreed that no taxes be imposed on land used for planting grapes.

German immigrant Leonard J. Rose arrived in Los Angeles in the early 1860s. He settled in the San Gabriel Valley on a ranch he called Sunny Slope and soon established himself as a vine grower and horse breeder. By the 1880s, his winery was producing four hundred thousand gallons of wine and one hundred thousand gallons of brandy annually. Rose served Los Angeles county as state senator for the term commencing in 1887, and also as a member of the State Viticultural Society, and of the State Board of Agriculture. A series of bad investments in California and Nevada between 1887 and 1897 led to his financial ruin. He committed suicide at his home in Los Angeles at the age of 72.

This period also witnessed the continued influence of other European immigrants. Irishman Matthew Keller established a productive vineyard in Los Angeles. Pierre and Jean-Louis Sansevain (nephews of Jean Louis Vignes) had purchased their uncle’s vineyard and winery, El Aliso, in the early 1850s. They expanded production, built new wine cellars, and were known for their award-winning, unadulterated wines.

Before California even became a state, it was Los Angeles that was poised to become the winemaking epicenter of the west coast. So much so that by 1850, the Los Angeles area boasted over 100 vineyards, and the city’s first-ever official seal, drawn up several years later, dubbed it the “City of Vines.” So how is it that L.A.’s northern neighbors won California’s winemaking crown, while the city’s own history as a land of vines faded into obscurity?

“It’s more of a tale of urbanization, unfortunately,” says Steve Riboli, who helps oversee winemaking operations at San Antonio Winery. Built in 1917 by Riboli’s great-great-uncle Santo Cambianica, an Italian immigrant, San Antonio is the last surviving downtown Los Angeles winery. The timing was unfortunate—as it was built three years before Prohibition—but a local church allowed Cambianica to make sacramental wine, one of the loopholes during that dry era. “We were able to survive because he was a very devout Catholic,” Riboli says.

In 1913, the arrival of water from Owens Valley via the aqueduct marked a pivotal moment. What was once a small city rapidly transformed into a metropolis, continually expanding, thriving, and reshaping its identity ever since. The post-war population boom sent land values skyrocketing, and the last of the vineyards were ripped out. “[During] that time period, the 1800s through the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, housing was just taking over everything downtown,” Riboli says. “So that’s what really destroyed the industry.” Soon enough, the only known vines in Los Angeles were the survivors clinging to old buildings.

But Northern California began developing, too. San Francisco began being served primarily by local vineyards and wineries. Worse, a strange ailment known as Anaheim Disease (later dubbed Pierce’s Disease) started to cause Los Angeles’ grapes to wither, then the roots to die altogether, starting in 1883. “Anaheim Disease, with its destructive and rapid rush through the vineyards, signaled the end of Southern California’s dominance in the wine industry,” wrote journalist Frances Dinkelspiel in her book Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California.

By 1890, Northern California had far surpassed its southern neighbors in winemaking production. Some former winemakers began planting other crops, such as oranges, instead.

Despite winemaking’s rich history in the region, there’s been little effort on Los Angeles’ part to reclaim that part of its identity. It may have to do in part with the industry’s dark past of abusing and misusing local Native Americans for their labor.

The wounds of this ugly history still resonate today, and is “something we have to do some reconciliation with,” Holland says. While Dinkelspiel says that these abuses are not yet widespread knowledge, “there is this gradual shift in public reception,” thanks to more information being released and acknowledged.

Though winemaking itself remains a side note in Los Angeles’ history, and one that’s not lauded due to the history of exploitation, its agricultural past and origins in viticulture remain curiously immortalized at the city’s most famous intersection: Hollywood and Vine, the symbolic crossroads of its two most influential industries.

The Gold Rush and the Movement of Wine Production North

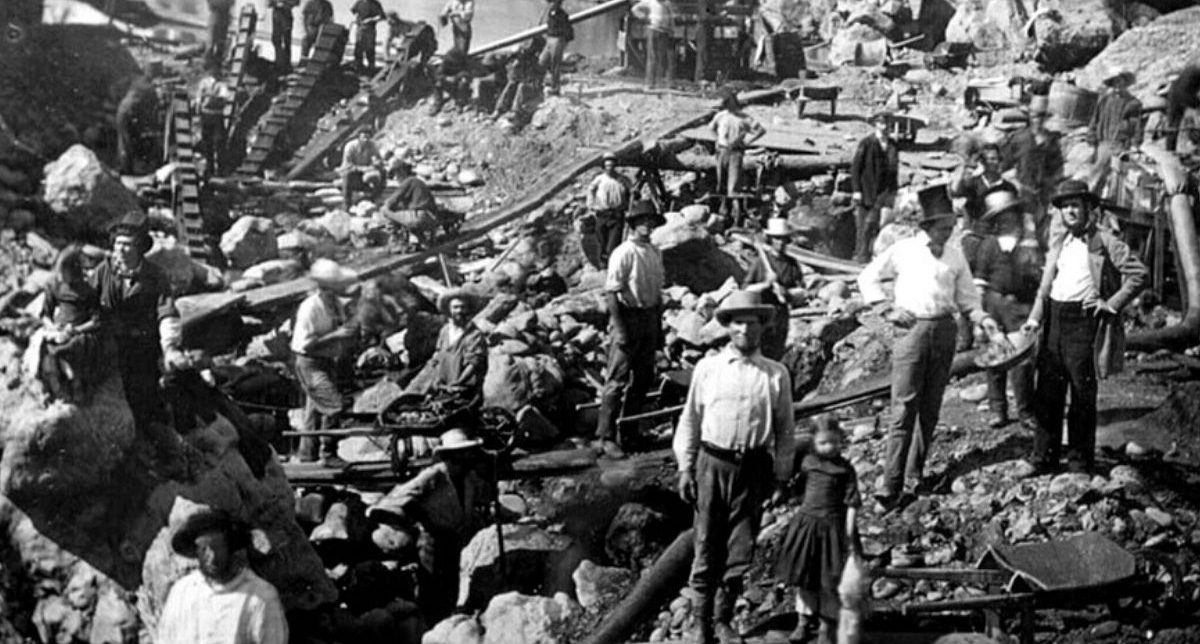

James W. Marshall found gold in Coloma in 1848, and his discovery sparked a frenzy of people, mainly young men, running out to California. Many of these prospectors were looking to strike it rich, or wanted an opportunity to rise out of poverty, or toiling in fields and factories.

During the Industrial Revolution, mining was dangerous, grueling work. Miners toiled all day and night digging for coal and precious metals. Although most of these miners worked for a company, the myth of the independent miner, digging in the wilderness for gold and jewels on their own, persisted. This myth came about because of the California Gold Rush and drove migration to the Sierra foothills.

The Gold Rush rapidly increased California’s population, and the state joined the union in 1850. In 1840, California had about 8,000 people. Just 10 years later, the population had grown to roughly 100,000. In 1848, the population of San Francisco swelled from 1,000 to 25,000 in that single year. By 1870, the population of the city had reached 100,000 people.

By 1849, the California Gold Rush was a frenzy for wealth. But while most prospectors had left by 1855 after realizing that their hopes for riches wouldn’t come to fruition, a few stayed, tilled the soil, and turned their skills at farming into success.

Sonoma Valley Pioneers

Recognizing that the temperate Mediterranean-style climate would be good for growing all types of crops, Catholic priests planted the first wine grapes in what would become Sonoma County in the early 1820s at the Mission San Francisco Solano, the northernmost and last Mission, constructed in 1823. Local Miwok, Wintun, and Wappo Native Americans who had converted to Christianity planted its vineyards, often under slave-like conditions.

In short order, Sonoma, aided by its myriad of soil types, terroirs, cooler climate, and easy access to shipping began developing before the Napa Valley.

After Mexico secularized the Mission system in 1834, General Mariano Vallejo, a Mexican military commander, the founder of Sonoma, and the eventual owner of 175,000 acres, transplanted many of the Mission’s vines to his own property, becoming one of the largest winemakers in the state.

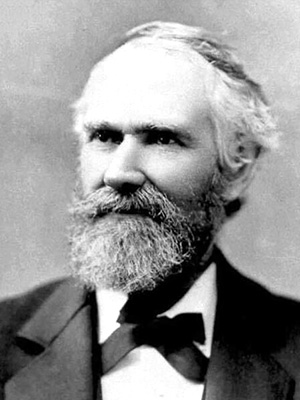

The first commercial winery in California, Buena Vista Winery, was founded in 1857 by Agoston Haraszthy, and is located in Sonoma. Haraszthy, a Hungarian immigrant, brought close to 100,000 grapevine cuttings from Europe, (predictably, mostly vines from Hungary) to the area in 1852, the introduction of the first European vines and grape varieties to California. Prior to Haraszthy, almost all the vines planted in California were of the Mission variety.

His initial idea was to plant in San Mateo and San Francisco. But the cold, foggy mornings caused him to seek sunnier land for his grapevines. Haraszthy went on to found the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society, which eventually became the Buena Vista Winery.

In 1859, after an extensive study on soils and climates for the cultivation of vineyards, the agricultural journal California Farmer published the first paper extolling the virtues of planting European grape varieties and the potential profits to be earned by growing grapes.

At the time of Haraszthy’s early plantings, land was cheap in Sonoma, selling for as little as $6 per acre. In time, due to his success, prices climbed to $150 per acre. Today, Sonoma vineyard acreage fetches $100,000 to $215,000.

Haraszthy’s viticulture and wine-making advances include digging his own caves for aging, perhaps the first California wine producer to do so. He hired crews of Chinese workers to create the cellars, using their experience with dynamite from railroad construction. He pioneered planting on hillsides, again often with Chinese labor. He installed one of the state’s first gravity flow presses at a time when most grapes were still crushed by feet. Because oak was hard to find, he began producing barrels from redwood to age his wine after figuring out how to remove the bitter taste of the wood. Following the European custom, he did not irrigate, he dry-farmed his vineyards, a practice many producers are returning to today.

By 1860, Haraszthy owned more than 5,000 acres of land. 1861 saw him return to Europe at the behest of California’s governor to find ways to improve winemaking in the state. Depending on sources, he collected between 100,000 and 200,000 cuttings of between 350 and 1,400 different grape varieties for planting in California for his vineyards, as well as those of other growers in the region. In 1862, with a total production estimated to be close to 15,000 cases, he was successfully bottling wine, mostly Zinfandel.

Other grape varieties planted in his vineyards included Riesling, Traminer, Flame Tokay, Black Morocco, and Sultana. During the 1860s the most popular California wines were white wines, sweet wines, and by 1870, sparkling wines. The level of production for the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society in the 1860s eventually rose to 50,000 cases of wine per year!

The Buena Vista sparkling wine sold for the princely sum of $1.00 per bottle. While this was less than the cost of true Champagne, it was still expensive when you consider that average salaries were not much more than $1 per day. (Several U.S. producers still label their sparkling wines as “champagne.” The U.S. government allows the use of the term on U.S. brands established on or before March 2006, as long as the geographic origin accompanies the champagne term on the label. American brands created after this date are not allowed to use the term. The French, of course, discourage any foreign use of the word Champagne.

To grow the industry, Haraszthy needed like-minded people who shared his passion for wine. He began spreading the word of his success, hoping to bring other like-minded growers to northern California. In fact, he hired both Charles Krug and John Patchett, both of whom were Napa Valley pioneers.

Unfortunately, Buena Vista eventually went bankrupt. Haraszthy died in 1869, as legend has it, when an alligator in a Nicaraguan river ate him. Over the years he has become a legend, even earning the nickname “Father of California Viticulture.”

A year after Buena Vista, Gundlach Bundschu was founded in 1858. As those two estates were truly important commercial California wineries, it can be said that Sonoma is actually the official birthplace of the California wine industry in Northern California.

Other Sonoma pioneers include William McPherson Hill who planted the Old Hill Ranch vineyard in 1852. He is credited with making California’s first really famous Zinfandel as early as 1855, when he and General Vallejo owned the most extensive vineyards in Sonoma County.

The Madrone Ranch vineyard was planted by General William T. Sherman and General Joe Hooker in 1854. (Both generals played important roles in the Civil War.) This was soon followed by Chelli, Jackass Hill, Maggie’s Reserve, Martinelli Road, Saitone, Wellington, and other wineries.

Napa Valley Pioneers

The popularity of California wine exploded from its early years in the 1850s. In 1850, the total production of California wine was close to 30,000 cases. By the end of the 1860s, production expanded to 125,000 cases. By the close of the 1870s, it’s estimated that more than 1,000,000 cases of wine were produced each year!

Wild grapes probably grew in abundance in early Napa Valley, but it took settler George Calvert Yount to tap the area’s potential for cultivating wine grapes. Yount built one of the first homesteads in the area and was the first to plant grapes in 1839. The land Yount first began cultivating was given to him as a grant from the Mexican government, as California was not yet a state and was still part of Mexico. The famous town of Yountville carries his name.

While George Yount was the first person to seriously plant vines, Napa Valley history was made by John Patchett, who gets credit for creating the first official vineyard and winery in the Napa Valley. Patchett began planting vitis vinifera vines in 1854, started producing wine just three years later in 1857, and constructed his cellar in 1859. When Patchett made his first vintage, he used an old cider press instead of a proper grape press, as that was all he had.

The following year his wine received an official review, probably the first of any California wine. Published in California Farmer magazine, the review said, “The white wine was light, clear and brilliant and very superior indeed; his red wine was excellent; we saw superior brandy, too.” The winemaker was German immigrant Charles Krug, who would go on to form his own famous winery.

While living in San Francisco, Krug managed a German language newspaper and is said to have experimented with winemaking as a hobby. When Krug married Carolina Bale in 1860, her family offered land just north of St. Helena for her dowry, says Jim Lapsley, professor of viticulture and oenology at U.C. Davis. The Charles Krug Winery opened there in 1861 and is considered to be the first commercial winery in Napa Valley.

As noted previously, in those formative years, vineyards were initially planted with Mission grapes. In 1875, three leading California wine-making pioneers, Charles Krug, Henry Pellet, and Seneca Ewer created the St. Helena Viticultural Club, which later became the St. Helena Viticultural Society.

The St. Helena Viticultural Club consisted of other winemakers and vineyard owners who shared the same problems and dreams. Together they agreed that to improve the quality of California wines, they needed to remove the Mission grapes, focusing on cultivating French and Italian grape varieties as well as reduce the need for chaptalization, the procedure of adding sugar to grape juice or must prior to or during fermentation; it is also called sugaring. It is used to attain the necessary sugar levels to produce alcohol when the natural grape sugars fall short.

Krug’s success and leadership sparked a wave of new growth, and by 1889 there were more than 140 wineries in operation, including Beringer, started in 1876, and Inglenook founded in 1879.

Jacob Schram, another German immigrant, bought 200 acres on Mt. Diamond in 1862 and planted 30,000 vines. His winery, Schramsberg, gained fame after the author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote about it in his 1883 book, The Silverado Squatters. The wine became so popular that President Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States, served it in the White House at official functions.

Jacob Schram, another German immigrant, bought 200 acres on Mt. Diamond in 1862 and planted 30,000 vines. His winery, Schramsberg, gained fame after the author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote about it in his 1883 book, The Silverado Squatters. The wine became so popular that President Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States, served it in the White House at official functions.

After Schram died in 1905 the property languished until Jack and Jamie Davies purchased it in 1965. They decided to focus on making sparkling wine in the Champagne style, to great success. Reviving the Harrison tradition, every President since Richard Nixon has featured the company’s sparkling wine at the White House or some official celebration.

In 1868, Hamilton Walker Crabb purchased 240 acres of what was still farmland from the family of George Yount for $100 per acre, which is equivalent to over $3300 today. Still an amazing bargain, as this land eventually became the famous To-Kalon vineyard.

Did Crabb know whether this was great vineyard land, due to its mixture of slopes and elevations with its loam and gravel soils and rocks with clay soil on the valley floor? Or was it just blind luck? Regardless, what became To-Kalon, turned out to be one of the best vineyard sites in all of Napa. (From 1980 to 2010 the harvest was sold to Robert Mondavi.)

In 1872 Crabb founded Hermosa Vineyards. He was extremely successful, and by 1878 he was one of the largest vineyard landowners in Napa Valley. The early success of Charles Krug and Hamilton Crabb spurred other growers to cultivate vines in Napa.

In 1886, Crabb changed the name of his winery from Hermosa to the To-Kalon Wine Company, which by that time had become one of the best-known names making wine in Napa. The To-Kalon Wine Company produced red sweet wines labeled as Port, Sauternes, white wine, and brandy.

At its peak, Crabb’s To-Kalon Vineyard grew to 650 acres of vines. He was by then capable of producing close to 150,000 cases of wine. The vineyards were planted to several different grape varieties, including black Burgundy and Tannat, a grape that was in use in Bordeaux at the time.

In 1836, Mexican General Mariano Vallejo bestowed the 11,000-acre Rancho Caymus lands upon George Yount. This grant extended north from what is now Yountville, tracing the Napa River valley to the present northern boundary of the Rutherford appellation. In 1846, Thomas Rutherford, who had married one of Yount’s granddaughters, received a generous gift from Yount, approximately 1,000 acres at the northern edge of Rancho Caymus. Following this gesture, Rutherford embarked on grape cultivation and winemaking investments in Napa. By the 1880s, the Rutherford area had firmly established itself as one of Napa Valley’s premier wine regions.

In 1874, the Sunny St. Helena Winery, which has since changed names to Merryvale, was first cultivated by Joseph Ghisletta. The Cedar Knoll Vineyard was planted in the 1870s. By 1880, more than 3,500 acres were planted with vines with more than 40 wineries actively producing and selling wine. In just a decade, from 1880 to 1890, the number of plantings in the valley exploded from 3,500 acres to more than 18,000 acres and the number of wineries expanded to almost 200!

Corresponding with the burgeoning wine industry, the first large commercial winery opened in Napa in 1872, Uncle Sam Wine Cellars. Uncle Sam Wine Cellars had the capacity to produce and bottle up to 2,000,000 bottles of wine! By the 1880s, their business had almost doubled in size. Their location, on the Napa Riverbank, made shipping easy. They were soon followed by the Napa Valley Wine Company.

The Beringer winery was created in 1875 by brothers Jacob and Fredrick Beringer, who previously worked for Charles Krug. Simi came into being in 1876.

What became Inglenook was born in 1879. Founded by William C. Watson in 1873, Gustave Niebaum purchased the estate and turned it into one of the most famous wines of the day (now owned by Francis Ford Coppola). Producing what was thought of as a true Bordeaux-styled wine, Inglenook became even more popular after the wine won a gold medal at the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition. That same year, Charles Lemme began purchasing land and planting vines atLa Perla. The vineyard was sold to the Schilling family, owners of the famous spice company, before it was acquired by Spring Mountain Vineyard.

Inglenook wines were considered as some of the best California could offer, and they were soon provided to passengers on the Canadian Pacific Railroad in their First Class dining cars. By the time Gustave Niebaum died in 1908, he owned 300 acres of vines.

Beringer and Niebaum were not the only new vintners in the 1870s, John Benson cultivated the 84-acre Far Niente vineyard with plantings of Zinfandel, Chasselas, and Sauvignon Vert.

In 1876, Morris Estee founded Hedgeside Vineyards, just off the Silverado Trail. What makes this important is that Hedgeside was perhaps the first winery to plant Cabernet Sauvignon in Napa, producing a wine sold as a Claret. The vineyards used for Hedgeside are now owned by Quail Ridge.

Charles Hopper first planted what is now known as the Missouri Hopper Vineyard (named for his daughter rather than the state) in 1873. The parcel for this vineyard was purchased from George Yount. Now owned by the Beckstoffer family, a part of the original Missouri Hopper vineyard is used to produce Ulysses, a wine from Christian Moueix, a French wine maker famous for Petrus in France and Dominus in the U.S., as well as several other top wines from the region today.

While most of the plantings were done on the valley floor in those days, perhaps the first two emigres from Bordeaux to make their way to the Napa Valley, Jean Brun and W.J. Chaix, began planting on Howell Mountain in 1877. They formed the Nouveau Medoc winery, which is now better known as Chateau Woltner. The Woltner family went on to own the famous Chateau La Mission Haut Brion vineyards in Bordeaux for several decades.

Burgess Winery, also on Howell Mountain, was founded in 1870 when Charles M. Burgess bought 137 acres of land. The first plantings and winery in Conn Valley took place in 1875, under Germain Crochet. In 1880, William Angwin, a local pastor, planted a small vineyard on Howell Mountain. The town of Angwin is named after him. Winfield S. Keyes was another Howell Mountain pioneer, who began planting vines in 1888.

The 1880s were a good period for growth in the Napa Valley. While the Vine Cliff Vineyard was first cultivated in 1866, the winery came into its own by 1880. Owned by George S. Burrage at the time, their Vine Cliff Vineyard wine was probably the most expensive wine made in the Napa Valley, selling for a whopping $15 per case!

Charles Pritchard planted Zinfandel and built a tiny cabin on what became known as Pritchard Hill in 1880. Zinfandel quickly grew in popularity. In fact, there was a steamship that traveled regularly between San Francisco and Napa called the Zinfandel Steamer!

The Crane vineyard, named after Dr. George Crane, was planted starting in 1880. At its peak, Crane owned 300 acres of vines. Many of those acres were purchased for as little as $6 per acre! Dr. Crane hired an associate of Charles Krug, Henry Pellet, to make his wine.

Also in 1880, George Schoenwald planted the vineyard that is in use today by Ridge’s Monte Bello estate. In 1881, the Franco-Swiss Farming Company began cultivating a large portion of their 143 acres that are now used by Seavey Vineyards.

Alexander Valley, Dry Creek Valley, and the Santa Cruz Mountains were also first being cultivated in the late 1880s. In Calistoga, Chateau Montelena was created by Alfred Tubbs in 1882 when he planted 220 acres of land. Although his first plantings were not distinguished, returning from a trip to France he brought vine cuttings from Chateau d’Yquem and Lafite Rothschild! Tubbs was one of the first growers to begin planting Phylloxera-resistant rootstock, which would go on to save not only California vines but European ones as well.

Just a bit south, what later became Spottswoode was founded by George Schonewald in 1882 as well. Edward Stanly began cultivating 170 acres of land in Carneros in the mid-1880s. 1885 saw the birth of Ridge Vineyards, which was first cultivated by Osea Perrone, after he bought 180 acres of land in the Santa Cruz Mountains on the Monte Bello Ridge.

In the mid-1880s, the Eshcol Ranch was cultivated and developed by James and George Goodman. Today, it is the site for Trefethen vineyards. In 1889, Mayacamas, the first of the famous mountain vineyards in the Napa Valley, came into being thanks to John Henry Fischer.

A number of important Zinfandel vineyards were being planted in the latter part of the 19th century. The Hendry vineyard began being planted in the 1860s. The Library vineyard started to be cultivated in the 1880s. The Pagani vineyard was cultivated in 1884. Fortune Chevalier created Chateau Chevalier with 25 acres of vines, mostly planted to Zinfandel. The vineyard is now part of Spring Mountain Vineyard. Spottswoode began planting Zinfandel in the 1890s and Hayne Vineyard was planted in 1902.

The Moore vineyard in Coombsville was not far behind as it was planted in 1905. Vineyards were cropping up in other parts of Northern California in those formative years. George and William West founded the El Pinal Winery in 1858 in Stockton and Joseph Spenker began planting Zinfandel, Cinsault, and other grapes in Lodi during 1889, in what is known today as the Bechthold Vineyard.

During the formative years in Napa Valley, predictably most of the original pioneers were men, but that was not always the case. A notable exception, Josephine Tychson, in 1881 became the first female grower, vintner, and winery owner in the Napa Valley when she and her husband John Tychson planted vineyards on a 147-acre parcel of land in St. Helena. By the 1890s, Josephine Tychson had 65 planted acres. That vineyard eventually gave birth to Freemark Abbey and Colgin Cellars, with their aptly named Tychson Hill wine.

In the nineteenth century, California wine was usually sold by the gallon. The cost for wine varied from as little as .25 per gallon to $2.00 for the best wines. On average, a bottle of wine cost between 20 cents to 35 cents in the early 1860s. Yields were high, and growers could count on close to five tons per acre, or roughly 400 cases per acre.

In 1856, only 225 acres of Napa were cultivated with vines. From that point forward, the growth was incredible! 1866 saw 3,740 acres planted and in the peak year of 1875, 24,664 acres were planted. Slowly but surely, Napa Valley was beginning to thrive as a wine region.

It was not until 100 years later that Napa had the same amount of plantings as 1875. The decline took place due to Phylloxera, Prohibition, and the Great Depression, from all of which it took decades for the region to make a full recovery.

1890 proved to be an important year for the young, struggling California wine industry. Records show almost 11 million cases of wine were produced! To help promote the sale and reputation of all those millions of cases of wine, numerous vintners entered their wine into competitions held in Paris for the World’s exhibition. Several California wineries won gold medals! That same year, in 1890, the Nichelini Family Winery came into being. Located in Chiles Valley, the winery remains in the hands of direct descendants of Anton Nichelini, making them the only historical winery still owned by the original founding family in Napa Valley.

Although success was to be had, those early years were difficult and expensive for the pioneers of the California wine industry. Glass bottles were pricey and hard to find. It was not uncommon for producers to reuse empty bottles, especially those that originally contained imported wine. Because bottles were hand-blown and expensive to deliver, they could cost as much as .10 to .12 cents per bottle.

Exporting California Wine in the Formative Years of Napa Valley

Charles Kohler and John Frohling formed Kohler & Frohling Wines in 1854, (In what is now Jack London Historical Park between Kenwood and Sonoma) using purchased grapes, before planting their own vineyards in 1857. They began producing wine bottles at their Pacific Glassworks company in the 1860s. They needed the bottles for their own wines as well as to sell to other burgeoning California wineries and to supply the first distribution and export company for wine, Kohler and Frohling, one of the largest and most successful wine companies of its day. (Frohling was also one of the founders of Anaheim, which was established as a German-American wine colony in 1857).

Some of the early efforts at exporting California wine faced obstacles when competitors accused California wineries of fraud, adulteration of their product, and falsification on their labels. This continued for close to 20 years until California wine started earning popularity with consumers from outside the state. In addition, because tariffs were low, imported wine from France and Italy was sold cheaply. Bordeaux was seen as a wine of quality because people knew Bordeaux was produced from Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc. That was not the case with California wines of the time that were mostly the product of field blends and low-quality Mission grapes.

Following the end of the Civil War, California wine exports doubled from 100,000 cases to 225,000 cases by 1870. California wines were delivered to the east coast of America, especially New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore, and were exported to other regions, most notably, Europe (where negociants purchased the wine while still in barrel, bottled, and then sold it), South America, Central America, Mexico, Canada, and China.

In 1875, the federal government increased import taxes on European wines. That made shipping wine from California more financially competitive, and California began to dominate the domestic table wine market. However, the more expensive wines still tended to come from Europe.

The Phylloxera Epidemic

Phylloxera came to Europe in 1863 with the emergence of a specific root louse, a type of parasite similar to aphids, that attacks and kills the roots of a vine. The insects, native to the Mississippi valley of the eastern U.S., were brought to the famous English Botanical Gardens.

The louse has two life cycles, above and below ground, with an occasional bridge between the two. Eggs overwinter either in the soil or resting above it. After they hatch, lice below ground feed on a vine’s roots. Those above ground feast on leaves. The damage done by subterranean Phylloxera allows for soil-borne fungi to enter the wounds and kill the roots. Meanwhile, the lice on the leaves help spread the epidemic; they can be blown by wind to another plant.

Phylloxera spread like wildfire in Europe after being introduced, decimating most of the European vineyards. Close to 90% of all European grapevines were destroyed. Both famous names and the ordinary estates across Bordeaux, Burgundy, Italy, and other regions were ruined. It took only two decades for the incredible amount of destruction to take place!

As Phylloxera raged across Europe, it seemed inevitable it would return to America with renewed vitality. The first sightings of Phylloxera in the US seem to have taken place in Sonoma at Buena Vista vineyards. The insects appeared in Napa starting in 1877 and were in full force just before the turn of the twentieth century. Before the epidemic was over, more than 80% of the valley’s vineyard acreage fell victim to the destructive root louse.

In both the New and Old worlds, while several treatments were developed, including pumping poisonous gas into the soil and flooding entire vineyards, the only practical solution was to graft the old-world vitis vinifera vines onto indigenous American rootstocks like Rupestris and St. Georges, local varieties that had a natural resistance, but made poor quality wine. Once this treatment was arrived at, a young French native, Georges de Latour of Beaulieu Vineyards, was ready to sell this native rootstock to growers all over California.

Most California vineyards needed to be replanted using only local rootstocks. One of the most popular varieties being planted after Phylloxera continued to be Zinfandel. Those plantings explain why we have so many old Zinfandel vines in California.

While Phylloxera was one of the major issues facing growers of the day, none of the problems dulled the enthusiasm for making wine in the Golden State. Even the depression of 1873 to 1876 did not curtail the growth of the California wine industry. However, it’s important to note that growers during those years were faced with hard times and plummeting prices. Many previously successful vintners went bankrupt.

It took years for the fledgling California wine industry to recover. It took a combination of increased quality, the removal of Mission grapes, and better economic conditions to rebuild. In addition, it was also helpful that the small production of European wines due to the ravages of Phylloxera made California wine more popular than ever.

The Early Twentieth Century

The California Wine Association

The 1890s, were a turbulent time, when a glut of grapes depressed prices and competing San Francisco wine houses undercut one another to grab market share. The industry only stabilized after 1894, when seven wine houses merged their assets to create the California Wine Association (CWA). The CWA was a ruthless organization that launched a wine war against grape growers and mercilessly squashed small operators who did not want to join their operation. The CWA grew rapidly and gobbled up wineries and vineyards around the state, eventually controlling 80 percent of the production and sale of wine in California.

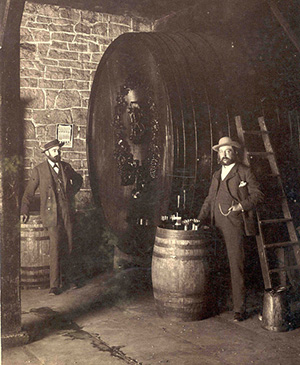

San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake and fire decimated most of the brick wine warehouses that had served as the hub of the California wine industry. After the devastation, which destroyed ten million gallons of wine, the CWA, headed by Percy Morgan, moved its facilities across San Francisco Bay to Point Molate, a promontory near the city of Richmond. The CWA constructed Winehaven, the world’s largest winery. Around 37 buildings, including one that resembled a medieval castle with crenellated parapets and corner turrets, were spread out on 47 acres that had a commanding view of the bay.

Winehaven was so large it was often referred to as a city-state, and it immediately became a tourist attraction for visiting dignitaries. At its peak, around 400 workers lived on the grounds in small bungalows or at the Winehaven Hotel. There was a crushing facility that could handle 25,000 tons of grapes, a cellar that could hold ten million gallons, a cooperage, and a bottling shop.

Rail lines came in from Napa, Sonoma, and San Joaquin counties, and a pier allowed huge ships from around the world to pull up and load barrels. At its peak, the CWA shipped 500,000 gallons of wine a month, with 40 ships departing to New York alone. The entire facility was shuttered by the time Prohibition went into full effect, and the CWA was left holding millions of gallons of wine it could not sell. The collapse of what was once the world’s largest wine company contributed to Percy Morgan’s suicide on April 19, 1920.

The U.S. Navy used Winehaven as a fuel depot during and after World War II, but it has been mostly vacant for decades. Amazingly, Winehaven is almost intact, although its buildings are in disrepair.

The Scourge of Prohibition

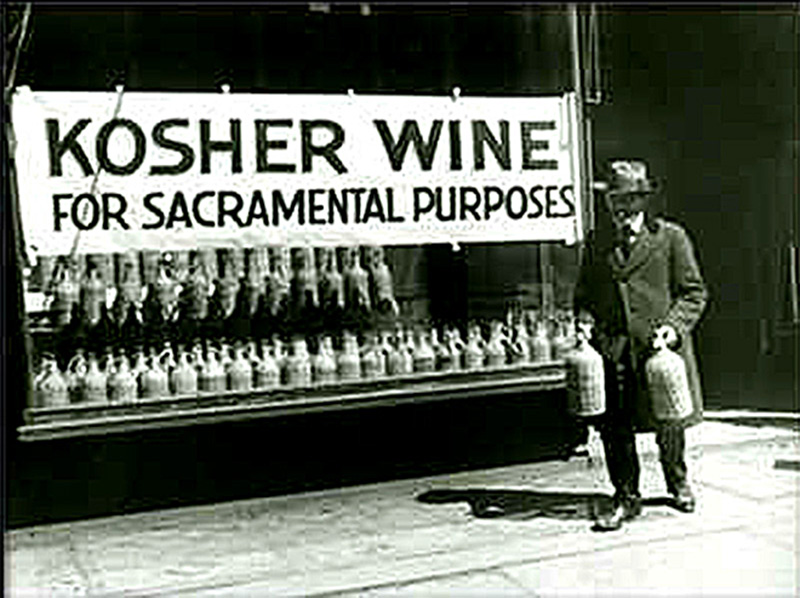

By 1920, California had become America’s leading winegrowing state, with over 1,000 wineries in operation. However, on January 16 of that year, the 18th Amendment, also known as the Volstead Act, ushered in the beginning of Prohibition, which declared the production and sale of alcoholic beverages (but not the consumption or possession) illegal. Vineyards were ordered to be uprooted, and cellars were destroyed.

A loophole in the law allowed each home to make 200 gallons of non-intoxicating cider and fruit juice per year, and thousands of Americans began to make their own wine at home. There were so many new amateur winemakers that the price for fresh grapes shot up. To meet the demand, growers throughout California tore out their fine wine varietals and replaced them with lower-quality grape varieties better suited to shipping.

Some vineyards and wineries were able to survive by converting to table grape or grape juice production. Some fortunate wineries, including Beringer, Inglenook, Louis Martini, Wente, and others had special dispensations for producing sacramental and medicinal wines, an allowed exception to the Prohibition laws. Nevertheless, most went out of business. Production had dropped 94 percent from 1919 to 1925. By the time that Prohibition was repealed in 1933, only 140 wineries were still in operation.

Despite Prohibition, by the end of 1921 Americans were drinking again at almost two-thirds the level they had before the law was passed. Eventually lawmakers gave in, and made alcohol of all types legal again in the United States. Even so, it would take more than half a century for winemaking in California to return to its pre-Prohibition volume

For a complete history of Prohibition, I highly recommend Last Call, The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent. His very first page describes the fear that had gripped the nation on the eve of enactment, “The streets of San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons, and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings, and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered on the last possible day before transporting their contents would become illegal. The next morning the Chronicle reported that people whose beer, liquor, and wine had not arrived by midnight were left to stand in their doorways, ‘with haggard faces and glittering eyes.’ Just two weeks earlier, on the last New Year’s Eve before Prohibition, frantic celebrations had convulsed the city’s hotels and private clubs, its neighborhood taverns, and wharf-side saloons. It was a spasm of desperate joy fueled, said the Chronicle, by great quantities of ‘bottled sunshine’ liberated from ‘cellars, club lockers, bank vaults, safety deposit boxes, and other hiding places.’ Now, on January 16, the sunshine was surrendering to darkness. Up in the Napa Valley, where grape growers had been ripping out their vines and planting fruit trees, an editor wrote, ‘What was a few years ago deemed the impossible has happened.’”

Happily, the California wine industry slowly recovered from Prohibition. Up until the 1960s, it was primarily known for its sweet port-style wines made from Carignan and Thompson Seedless grapes and jug wines. However, a new wave of vintners emerged, ushering in a renaissance period in California wine production with techniques strengthening the grape production, fermentation, and bottling processes.

Highlights of The Modern California Wine Industry

The wine industry is a dominant force in California agriculture, occupying a significant role both within the state and on a national scale. In 1945, very few growers existed, and of course, even fewer wineries were making wine. By 1955 there were 360 growers, and in 1965 232 wineries were active in California. 1975 saw 330 producers, which jumped to 712 by 1985. In 1995 944 estates were producing wine, in 2005 2,275 producers were making wine and today there are close to 4,000 wineries in California.

Wine grape acreage expanded from just over 100,000 acres in 1960 to nearly 600,000 acres in recent records. Between 2008 and 2017, there was a notable increase of 70,000 acres in the number of bearing acres of wine grapes, indicating a continued upward trajectory in the industry’s growth. This transformation in land use is evident to observers across the state, particularly along Interstate-5 in the Central Valley, where vineyards have replaced orchards.

Within California’s agricultural landscape, vineyards harvested over 590,000 acres in 2018 alone, yielding over 4,285,000 tons of grapes valued at over $4.3 billion. Remarkably, California wine emerged as one of the top export commodities for the United States in 2018, ranking fourth among all agricultural products. California wines constituted over 91% of US wine exports, valued at nearly $1.5 billion in the same year. These wines are shipped worldwide, with key markets in the European Union, Canada, Japan, and China.

Beyond its economic impact, wine plays a significant cultural role, serving as a symbol of California’s identity and attracting tourism dollars to wine regions throughout the state. As a cultural ambassador, California wine fosters trade relationships and enhances the state’s global reputation, showcasing its rich heritage and contribution to the world of wine.

Father of the Modern Era: Andre Tchelistcheff

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Napa Valley’s wine industry began its slow recovery. During this time, John Daniel Jr. resurrected Inglenook, Louis M. Martini built his winery, and the Mondavi family purchased Charles Krug Winery. Georges de Latour re-established Beaulieu Vineyards. Andre Tchelistcheff, a Russian émigré working in France, came to Napa Valley to work for BV in 1938 and became one of the great figures and mentors in the history of Napa Valley wine.

Tchelistcheff was responsible for introducing many of the modern winemaking techniques that were used in Europe. It was Tchelistcheff who began thinking about frost protection during the growing season. He pioneered the need for proper sanitation and the use of small, French oak barrels for the aging of the wine instead of the more common redwood barrels of the time. He also insisted that malolactic fermentation (a biochemical reaction where bacteria converts malic acid to lactic acid and carbon dioxide, making the young wine softer, smoother and more complex) become part of the wine-making process. He eliminated pasteurization, and introduced the technique of cold fermentation to increase the color and concentration of the wine. He began replanting the vineyards with higher levels of density, reducing the amount of sulfur used in the vineyards, and more importantly, he focused on planting high-quality French grape varietals.

The Emergence of Single Vineyard Wines