My Favorite Wines of 2024

Every critic needs a year-end list, right? Here are my three favorites from 2024:

A wine buying guide for the curious wine enthusiast.

My Favorite Wines of 2024

Every critic needs a year-end list, right? Here are my three favorites from 2024:

Note: This isn’t really a blog post, but rather a long-form essay.

If you would prefer a printed copy for reading, click here for the PDF.

For an edited “Reader’s Digest” version of this essay that is about half as long, the PDF is here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Spanish Colonization

The Spanish Mission System

The Establishment of Missions throughout California

Fray Juniper Serra and His Missions

The Exploitation of Native Americans

Southern and Central California As The First Wine Region

Missions Founded in San Luis Obispo County

Los Angeles as a Wine Making Center

The Gold Rush and the movement of Wine Production North

Sonoma Valley Pioneers

Napa Valley Pioneers

Exporting California Wine in the Formative Years of Napa Valley

The Early Twentieth Century

The California Wine Association

The Scourge of Prohibition

Highlights of the Modern California Wine Industry

Father of the Modern Era: Andre Tchelistcheff

The Emergence of Single Vineyard Wines

The Judgment of Paris

The Mondavi Family

The Elephant in the Room: Robert Parker

The Amazing 1990s

California Cult Wines

Jean Phillips and Screaming Eagle

Bill Harlan

David Abreu

Andy Beckstoffer

Helen Turley

Contemporary Grapes and Wines

California Wine Regions

American Viticultural Areas

The North Coast

Napa Valley

Sonoma Valley

The Central Coast

A Renaissance in Southern California

The Temecula Valley

Notable Ethic Groups

Native Americans and Mexican-Californios

Chinese-Americans

Italian-Americans

Mexican-Americans

Challenges and Opportunities in the California Wine Industry

Although my observation is that the risk of cork taint in wine has been reduced over the past couple of decades, it does still exist, and some even maintain that it is an increasing problem, affecting up to 5 percent of wines. Cork taint is the result of a chemical compound that can occur in the bark of cork trees (a type of oak grown in Spain and Portugal) 2,4,6-Trichloroanisole or TCA, which produces a musty, moldy odor that people are sensitive to in varying degrees. Although harmless to health, it is a fault that negatively impacts the enjoyment of a wine. Whether because of this risk or other factors such as cost or convenience, some producers have turned to other ways to close their wine bottles. These include corks that are made from bark that has been ground up, processed to eliminate TCA, and reconstituted as corks; synthetic stoppers manufactured to look and feel as much as possible like natural cork; ever-increasingly popular screw caps; rarely-seen glass stoppers; and plastic plugs. Plastic plugs are my absolute least favorite solution. They are hard to extract, hard to reinsert, and regardless of what the plastics industry continues to assert, nearly impossible to recycle.

L to R: Sensei, Karatamba, Momokawa Heart and Soul, Kiku-Masamune Taru.

L to R: Sensei, Karatamba, Momokawa Heart and Soul, Kiku-Masamune Taru.

Let’s be clear about this right away: Saké, the national alcoholic beverage of Japan, is often called rice wine, but this is a misnomer. While it is a beverage made by fermentation, the production process more closely resembles that of beer, and it is made from grain (rice, of course), not fruit. To make saké, the starch of freshly steamed glutinous rice is converted to sugar and then fermented to alcohol. Once fermented, the liquid is filtered and usually pasteurized. Sakés can range from dry to sweet, but even the driest retain a hint of sweetness.

History

Saké is an ancient drink, so much so that its origin has been lost in the mists of time. Ironically, the earliest reference to the use of alcohol in Japan is recorded in a third-century Chinese text, the Book of Wei in the Records of the Three Kingdoms which wrote of Japanese party habits. The Kojiki, Japan’s first written history, compiled in 712, is the earliest to mention alcoholic beverages in Japanese itself. Historians place the probable origin of true saké (which is made from rice, water, yeast, and kōji mold (aspergillus oryzae) in the Nara period (710–794).

Saké production was a government monopoly until the 10th century, when temples and shrines began to brew saké as an essential part of religious ceremonies, evolving into the main centers of production for the next 500 years. That being said, the saké of antiquity was not the same as the clear beverage we know today. It was reserved for nobles and priests, and was thick and milky or yellow in color, with a low alcohol content.

In the 16th century, the technique of distillation was introduced into the Kyushu district from Ryukyu. This led to shōchū (literally, fiery spirits), a beverage typically distilled from rice (kome), barley (mugi), sweet potatoes (satsuma-imo), buckwheat (soba), or brown sugar (kokutō), though it is sometimes produced from other ingredients such as chestnut, sesame seeds, potatoes, or even carrots. It usually contains 25% alcohol by volume, and is most often used as a beverage outside of meals.

During the Meiji Restoration, laws were written that allowed anybody with the money and know-how to construct and operate their own sake breweries. Around 30,000 breweries sprang up around the country. As time passed, the government levied increasing taxes on the saké industry and the number of breweries eventually dwindled to 8,000.

Once the 20th century arrived, saké-brewing technology advanced beyond the centuries-old traditions. The government opened a saké-brewing research institute in 1904, and in 1907 the first government-run saké-tasting competition was held. Yeast strains specifically selected for use in brewing were isolated, and enamel-coated steel tanks came into use, which were easier to clean than the traditional wooden barrels, lasted forever, and were devoid of bacterial problems.

During the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–1905, the government banned the home brewing of saké. At the time, saké comprised 30% of Japan’s tax revenue. Home-brewed saké was not taxed, so the thinking was that by banning it sales and tax revenue would increase. This ban ended home-brewed saké, and the law remains in effect even today.

World War II brought rice shortages, and the saké-brewing industry was hampered as the government discouraged the use of this essential food for brewing. Postwar, breweries slowly recovered, and the quality of saké gradually increased. Even so, beer, wine, and spirits became increasingly popular in Japan, and in the 1960s beer consumption surpassed saké for the first time.

While the rest of the world may be drinking more saké and the quality of saké has been increasing, production in Japan has been declining since the mid-1970s. Predictably, the number of saké breweries is also declining; there were 3,229 Japanese breweries nationwide in 1975, but the number had fallen to 1,845 by 2007.

Courtesy of Ozeke Saké

Ingredients

As noted earlier, saké is made from just four ingredients: rice, water, koji, and yeast. With so few components, the quality of each is crucial. Akita is known for its high-quality rice. Some of the best water is found In Nada near Kobe, where rivers course through granite canyons, or Fushimi with its pure spring water.

Although saké breweries often pride themselves on the quality of the rice and local spring water that they use, unlike wine this does not translate into terroir, as the brewing process effectively cooks out any such nuances.

Rice Polishing, Washing, and Soaking

The rice used in saké is called “saka mai” in Japanese, and it is not the same type of rice as food rice. The grains are larger, contain more starch, and have less protein and fat. The rice is first milled, aka “polished,” to remove the outer layer that could cause off-flavors in the finished product. Typically, this milling will be 25 to 70%, but I have heard of exotic sakés with 99% starch removal! Not surprisingly, the more the rice is milled, the more expensive the saké becomes. As an example, it takes 800 grams (28 ounces) of polished rice to make 720 mL (the size most like a wine bottle) of Ginjo saké. (Ginjo designates that at least 40% of the rice has been polished away.)

After polishing, the rice is soaked, either by machine for simple sakés, or by hand for higher-quality ones. Next the rice is steamed. Unlike rice for the dinner table, which is typically simmered in hot water either in a pot or automatic rice cooker, saké rice is prepared by steaming, which allows the rice to maintain a firm outer texture and soft center, thereby helping the brewing process. It is this heating step that more closely aligns saké with beer, which also requires heating, rather than wine, which must not be heated.

Rice Cooling

The rice must be cooled after it has been steamed to the desired degree. Large breweries use a refrigerated conveyor system to lower the temperature, while craft brewers rely on traditional methods of tossing and kneading to adjust the temperature, giving the brewmaster more precise control.

Koji Making

The heart of a saké brewery is its “koji muro”, the cedar-lined room in which koji is made. It is kept at 86 to 90 degrees F. (30 to 32 degrees C.), making it much like a sauna, so you have to enjoy warm weather to work there! Cedar has natural anti-bacterial resins which help to create a clean environment conducive to efficient koji production.

Koji requires 48 hours to prepare, during which the rice is inoculated with koji mold spores, and carefully kneaded in controlled temperature and humidity. The mold converts the starch in the steamed rice to glucose, and microorganisms multiply to create a snow-white fuzz with a strong, sweet fragrance. The finished koji will be about 20 to 35% of the rice used in the production of the saké, depending on the recipe.

Fermentation

Once the koji is ready, it is mixed into chilled spring water and yeast in a fermentation tank, and then the steamed rice is added. The tank is filled gradually, in three stages over a four-day period. This allows the yeast to retain its strength to keep consuming sugar and producing alcohol throughout the fermentation period, which typically continues for 21 days. The temperature is maintained at 46 to 64 degrees F. (8 to 18 degrees C.). The brew, called “moromi,” is stirred on a daily basis to ensure consistent fermentation. Each day, tests are performed to check specific gravity, acidity, and alcohol content.

Pressing And Racking

Once the moromi reaches maturity as determined by the brewmaster, in a craft brewery it is drained into cloth bags which are placed in the traditional “fune” press which works with gravity and hand-applied mechanical pressure. The first run of saké starts emerging from a spout at one end of the press under the natural weight of the filled bags, resulting in a light-and-fruity first-pressed sake known “arabashiri.”

In a large commercial brewery the moromi is machine-pumped into a large accordion like hydraulic press called a “yabuta.” Activated charcoal is usually added to the pressed saké and then filtered out.

Bottling

Once pressed and racked the saké may either be bottled immediately or temporarily tank-stored at close to 32 degrees F. (0 degrees C,). “Go” is the measurement unit traditionally for saké. One go is about 180 mL. Saké bottle sizes are also based on these units, with the most common sizes being: 180 mL (1 go; about 6 ounces); 360 ml (2 go); 720 mL (4 go); and 1800 mL (10 go, the magnum-like bottle you often see in izakayas, informal Japanese bars that serve alcoholic drinks and snacks. The glass may be either green, brown, or clear. After bottling, most sakés are pasteurized.

Storage and Consumption

The entire saké production process takes about 45 to 60 days from start to finish. There are no vintage years, and the product is best consumed within the year it is bottled, as aging does not enhance its flavor in any way, and indeed may degrade it. Once a bottle is opened, it should be refrigerated and drunk fairly quickly.

Grades of Saké

Saké is divided into two main categories. Jozo-shu is made with added alcohol, and junmai-shu is not.

Jozo-shu

Futsu-shu is ordinary table saké and the most widely consumed grade. It is best served warm, and is suitable for use in cooking.

Honjozo-shu is made with better-quality rice, and a higher proportion of the alcohol is produced during fermentation rather than being added.

Honjozo-ginjoshu and honjozo-dai-ginjoshu are the highest grades of alcohol-added saké. They are made with more care from top-quality rice. They should be served cold.

Junmai-shu

Junmai-shu is similar to honjozo-shu, but relies on all of its alcohol from the fermentation. It is more likely than jozo-shu to be found in the U.S., and can be served warm (not hot) or cold.

Junmai-ginjoshu and Junmai-daiginjoshu are the highest grades of junmai-shu. Like the highest grades of jozo-shu, they are made with more care from top-quality rice. 50 to 70% of the rice is polished away, respectively. They should be served cold.

Serving Saké

L to R: glass carafe and cup, masu, and two tokkuri with matching ochoko.

The glass carafe above is used for serving cold saké. The blue cavity is filled with ice to keep the saké cool. The wooden box is a “masu.” In addition to being a drinking vessel, it was also traditionally used for measuring rice, appropriately. In traditional restaurant service, the masu is placed on a small saucer and filled until the saké overflows, thus ensuring an honest pour. Some people, particularly native Japanese, will add a small pinch of salt to the corner of the masu before drinking, but I don’t recommend doing so.

In Japan, the process of heating saké is called “okan suru” and the resulting warm saké is called “kanzake.” The ceramic pots used for the heating are “tokkuri,” and the accompanying cups are “ochoko.” These are usually sold as sets, and are available in a very wide variety of styles. And, “warm” is the operative word here. Most heated sakés, both at home and in restaurants here in the U.S., are made too hot. Warm saké should be about 108 degrees F. (42 degrees C.). If you like it a bit hotter, the limit is around 122 degrees F. (50 degrees C.). Heating releases saké’s bright rice aroma, and causes the alcohol to be quickly absorbed into the blood.

In addition to it being a beverage, saké is also used as one of the principal seasonings in Japanese cooking, the other three being dashi stock, fermented bean paste (miso), and soy sauce. Saké acts as a food tenderizer due to the amino acids it contains. It also can suppress saltiness, eliminate fishy tastes, and take away strong odors. It is used sparingly in cooking, and as with wine, only use saké that you would drink on its own.

An important gauge of saké is the SMV (Saké Meter Value). This measures the density of saké relative to water, and is the method for determining the dryness or sweetness of saké. The higher the SMV, the drier the saké. The range is -15 to +15.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

OK, if you’re reading this I have to assume you enjoy wine, but don’t know much about it, and would like to become more knowledgeable. In that case, you are the very person that Winervana is intended for. So, how can you learn more about wine?

First, drink more wine! Now, this isn’t a call for overconsumption, but rather for broadening your wine horizons. If you gravitate towards Cabernet Sauvignon, try some Merlots. If you like Chardonnay, try Pinot Grigio. If you mostly drink wines from the U.S., sample some from Europe. At a more basic level, if you usually drinks reds, include some whites, or the other way around. And definitely dive into some Rosés! You get the idea.

Rely on wine professionals. These can include salespersons at your local wine shop as well as sommeliers at high-end restaurants. Don’t be intimidated that these people know more about wine than you do. Of course they do, that’s their job. Their job is also to sell you something you might like rather than make you feel ignorant. (If any of these people does that, immediately take your business elsewhere.) Feel free to provide as much information as possible, like “I don’t like sweet wine.” “I only drink sweet wine.” “I prefer wines from Hungary.” (Hey, it could happen.) “I like the idea of organic wines, but can’t seem to find any.”

Rely on wine professionals. These can include salespersons at your local wine shop as well as sommeliers at high-end restaurants. Don’t be intimidated that these people know more about wine than you do. Of course they do, that’s their job. Their job is also to sell you something you might like rather than make you feel ignorant. (If any of these people does that, immediately take your business elsewhere.) Feel free to provide as much information as possible, like “I don’t like sweet wine.” “I only drink sweet wine.” “I prefer wines from Hungary.” (Hey, it could happen.) “I like the idea of organic wines, but can’t seem to find any.”

I myself am not a particular fan of Rieslings. Before I pretty much gave up on them, I told the seller at a local wine shop that I kept hearing about how versatile and food-friendly Rieslings were, and I really wanted to find one I could embrace. It would need to have only a little spiciness or floweriness. It would need to be bone dry. It would need to cost about 20 bucks. He suggested a wine from Sonoma, which I sort of enjoyed, but didn’t make me a convert. (Although this one just about did.) So, guidance from a pro won’t always ensure success, but it will certainly increase the odds in your favor.

And, never, never feel embarrassed about price. Any time you are dealing with a wine seller, don’t hesitate to tell them, “I don’t want to go above X dollars for this purchase.” Again, if the seller can’t respect that, go elsewhere.

Host a wine tasting party. Invite six to eight friends for the party. Each person should bring a bottle of wine made from the same variety, such as Syrah, and all the bottles should be roughly in the same price range, which you can specify in the invitation, like $20 to $25. (If you have a wealthy friend, it can be amusing to have that person bring a “ringer,” a bottle that costs four or five times what was called for in the invitation. This is a good way to reveal that price and quality are not necessarily in lock step.) When people arrive, you should wrap the bottles in individual brown paper sacks or in aluminum foil with just the neck exposed, write a number on each one with permanent marker, and pull the cork. Sit down at a comfortable location, give everyone a piece of paper, a pen, a wine glass, a glass of water, perhaps some bread sticks, and start tasting the wines one at a time. I suggest going with pours of no more than one or two ounces for the tasting session, much like you would get at a winery’s tasting room. Wine left over can be consumed as people socialize afterwards.

Follow the six esses: see the color of the wine, swirl it in your glass, smell it, sip a little, swish it around in your mouth, and then swallow or spit. (Spitting is how professionals can taste dozens of wines at a time and remain lucid. All well and good, but it is unlikely to happen at a home party, where the point is to have fun as well as learn about wine.) Write down your impressions. Taste through all the wines, then talk about them as a group and hear what people liked and didn’t like. Once you’ve tasted all the wines, take them out of their wrapping one at a time, and next to the notes you made about that wine, write down the vintage year, the winery, where it was made, and how much the bottle cost. If you hold on to these notes, they can be the foundation of your wine education, a growing ability to remember what style of wine you like, along with what wineries you think make good wine. With any luck, your guests will all host parties of their own. That would give everyone a chance to try 36 to 64 different wines!

Consider a wine club. Here are some examples:

https://www.goldmedalwineclub.com/

Nearly all of these clubs offer a first case at a loss-leader price, with the wines often costing about $10 per bottle. After that, they want to ship you a case of wine on a regular basis, usually quarterly. I have tried a number of these clubs., but, I am no longer active with any of them. I still recommend that you give a few a try, though. You will be exposed to wines and producers you never heard of, from all around the world. I think the best plan is to buy that first case, try the wines, and then cancel and move on to another club. If you do this, say, once every three months for a year, you will have tried 48 new wines and expanded your palate for the better. You will like some wines more than others, which is the whole point, and you might even get lucky and discover one you love.

Almost every winery has a club of their own, as well. These usually ship two or three bottles on a monthly or quarterly basis. But, I suggest you hold off on these until you have focused your tastes on what you really like. I myself have been a member of Cline, Clos Pegase, Keenan, and Truchard for years.

I was also a long-time member of V. Sattui, until the owner, Daryl, aka “Dario,” drove me away by his arrogant attitude. I won’t bore you with the details, but it was unfortunate because the wines are quite good and only available directly from the winery. However, I have no interest in supporting a producer who doesn’t care about his customers, or one who won’t respect your intelligence or your budget, and neither should you.

There are plenty of wine courses, catering to every level. As a way to increase your wine knowledge, these can range from easy and nearly effortless, to a real commitment of both time and money. It all depends on what suits you. Here are just a few:

There are plenty of wine courses, catering to every level. As a way to increase your wine knowledge, these can range from easy and nearly effortless, to a real commitment of both time and money. It all depends on what suits you. Here are just a few:

World of Wine: From Grape to Glass

Introduction to Wine and Winemaking from U. C. Davis

And, there are thousands of wine-related videos on YouTube.

Finally, there is self-education through reading. There is a wealth of resources both in print and online, such as right here at winervana.com. One of the books I rely on is The New Wine Lover’s Companion by Ron Herbst. Jon Bonné’s The New Wine Rules is great for demystification. Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson’s The World Atlas of Wine is just that, a comprehensive overview of wine places, terroir if you will. Kevin Zraly’s Windows on the World Complete Wine Course is highly regarded. And Robert Parker’s Wine Buyer’s Guide, although definitive, is like drinking from a fire hose. (Parker retired in 2019, so his seventh edition from 2008 is likely to be the last.)

There are magazine’s too, of course, such as Wine Spectator, Wine Enthusiast, Decanter, and Imbibe. But frankly, these can be overwhelming for the casual wine drinker, especially the first two. I read them occasionally, but don’t subscribe, and, predictably, find their numerical rating systems capricious and rather unhelpful.

Drink more wine!

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

These days, wine drinkers are increasingly seeing the words sustainable, organic, and biodynamic on wine bottles and in wine producers promotional materials. Stewardship of the land and the lack of chemicals sound appealing, and who doesn’t like something that is dynamic? But what, really, do these terms mean? In fact, they are not just amorphous “feel good” terms, but do have specific definitions as well as institutional certifications to go along with them.

These days, wine drinkers are increasingly seeing the words sustainable, organic, and biodynamic on wine bottles and in wine producers promotional materials. Stewardship of the land and the lack of chemicals sound appealing, and who doesn’t like something that is dynamic? But what, really, do these terms mean? In fact, they are not just amorphous “feel good” terms, but do have specific definitions as well as institutional certifications to go along with them.

Note: These criteria and certifications only specifically apply to wines made in the United States. Other nations may or may not have similar programs.

When a wine is termed sustainable, it means the winery engages in eco-friendly practices such as using drip irrigation or dry farming; limiting or eliminating chemical waste and the use of pesticides; replanting crops or trees to replace those harvested for production; reducing the winery’s carbon footprint; using cover crops between vineyard rows to improve soil health; prevent erosion, control vine vigor, discourage weeds, and promote the sustainable health of the vineyard; deploying beneficial insects to control pests whenever possible; recycling packaging; taking part in energy efficiency initiatives; wildlife conservation; and other ‘green’ initiatives. Sustainability basically implies that the business is leaving as little negative impact on the land as possible.

Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing (CCSW) is a statewide certification program that provides third-party verification of a winery’s commitment to continuous improvement in the adoption and implementation of sustainable winegrowing practices.

Sustainability in Practice (SIP) Certified helps farmers and winemakers demonstrate their dedication to preserving and protecting natural and human resources.

Global Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) Certification is an internationally recognized system that sets standards to ensure safe and sustainable agriculture and ensure product safety, environmental responsibility and the health, safety, and welfare of workers.

The Napa Green organization supervises two programs. Land is an umbrella program that recognizes growers with validated environmental compliance and verified farm plans as meeting standards for watershed stewardship. Winery is one of only four sustainable winegrowing programs nationwide, offering the opportunity for comprehensive soil-to-bottle certification in both the vineyard and winery.

The California Sustainable Winegrowing Alliance is a certification program that provides verification that a winery or vineyard implements sustainable practices and continuous improvement.

Organic wines are about the protection of natural resources, to promote biodiversity, and limit the use of synthetic products, especially in the vineyards. Organic wines are made with organic grapes, of course. That starts with the use of no synthetic pesticides in the vineyard. Once the vinification process begins, substances like commercial yeast must also be certified as organic. Further, for the wine itself to be organic, there can be no sulfites added during production, although some sulfites do occur naturally in all wines. Sulfites are chemicals used as preservatives to slow browning and discoloration in foods and beverages, including wine, during preparation, storage, and distribution. Sulfites have been used in wine making for centuries, but some people are sensitive to them. If you’re not asthmatic, sulfite sensitivity would be very unusual. If you do have asthma, your chances of being sensitive to sulfites is in the range of between 1 in 40, and 1 in 100. (I myself am asthmatic, and have no sulfite sensitivity.)

Certification is an arduous, three-year process during which producers have to transition vineyards by discontinuing any use of prohibited substances. To be “Certified Organic,” wines must meet the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program’s criteria in both farming and production, as well as requirements set by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

Biodynamic is the most rigorous of these three protocols. Although based on both sustainable and organic, it goes much further. It is a spiritual-ethical-ecological approach to agriculture, gardening, food, and nutrition. Biodynamic wine is made with a set of farming practices that views the vineyard as a complete organism. The idea is to create a self-sustaining system with natural plants, materials, soils, and composts. Chemical fertilizers and pesticides are forbidden. Instead, a variety of animals and insects will typically live in the vineyard to fertilize it and control pests. Biodynamic farming also has an association with ancient agricultural concepts such as following lunar growing cycles and astrological charts, connecting the earth, the vines, and the solar system. (This last part gets a little squishy, imho.)

And more than just concept, Biodynamic is a registered trademark of Demeter Association, Inc., the United States’ branch of Demeter International, a not-for-profit incorporated in 1985 with the mission to enable people to farm successfully in accordance with Biodynamic® practices and principles. Demeter’s vision is “to heal the planet through agriculture.”

The Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard applies to the certification of farms and ranches for the purpose of allowing them and their resulting agricultural products to carry the Demeter certification marks Biodynamic®, Demeter® and Demeter Certified Biodynamic®. The Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard meets the minimum requirements set by Demeter International. These base standards form a common legal foundation and agricultural framework for Biodynamic practice worldwide.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

Here at Winervana, I use this disclaimer, “Although you will see vintage dates throughout Winervana, I don’t put too much importance on them. Major producers these days strive for a consistent style, year after year, and largely succeed. For instance, when shopping for a particular wine, if you have a choice between a current release and one that’s a few years old, there will certainly be differences in price and the character of the wine. But upon release, those two examples of the same wine are likely to be quite similar.”

Here at Winervana, I use this disclaimer, “Although you will see vintage dates throughout Winervana, I don’t put too much importance on them. Major producers these days strive for a consistent style, year after year, and largely succeed. For instance, when shopping for a particular wine, if you have a choice between a current release and one that’s a few years old, there will certainly be differences in price and the character of the wine. But upon release, those two examples of the same wine are likely to be quite similar.”

To test that position, I acquired a “vertical” of three Brutocao Cabernet Sauvignons. A vertical tasting is simply the same wine from different vintages. These three selections were indeed quite similar. Sourced from Brutocoa’s estate vineyards in Mendocino county, they all were aged 18 months in oak, 50% French and 50% American, and all have an ABV of 14.5% and .69% acidity.

These wines are a deep garnet in the glass. Surprising for Cabernet Sauvignon, they are semi-transparent rather than opaque. They start, predictably, with aromas of dark fruit, particularly blackberry, with hints of cedar. Those dark fruits continue on the palate, but these wines are restrained instead of fruit-forward, perhaps to be expected from a producer with a strong Italian heritage. They have a medium-long finish that features black-tea tannins.

There were subtle differences, however. Nothing that you would notice tasting the wines weeks or even days apart, but they were there. The 2015 had the highest levels of perceived acidity (all three were bottled at .69%) and tannins. Very unforeseen, because the common wisdom is that as a wine ages in the bottle both acidity and tannins become softer, rounder, and more balanced. Go figure. The 2016 was the most integrated of these selections, with well-balanced acidity and tannins, both less demanding of attention than in the 2015. Finally, the 2017 fell between the other two, with slightly more acidity but softer tannins than the 2016.

You can read more about Brutocao here: https://winervana.com/brutocao-cellars/

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

Riedel of Austria, famous for its varietal-specific stemware, makes both of these glasses, and both are intended for use with brandy and its variants Cognac, and Armagnac. How is this possible? They could hardly be more different.

L: Riedel Brandy Snifter / R: Riedel Cognac Hennessey Glass

L: Riedel Brandy Snifter / R: Riedel Cognac Hennessey Glass

The glass on the left is the iconic brandy snifter, as instantly recognizable as a martini glass. Its large balloon bowl is intended to display as much of a brandy’s aroma as possible. And the wide bottom is intended for cradling in the palm of your hand, warming the brandy to further enhance the nose.

The glass on the right, although named by Riedel specifically for Hennessey Cognac, is suited for any brandy, Cognac, or Armagnac, and is the one preferred by connoisseurs and professionals. The bowl still allows for appreciating the aroma, without accelerating the evaporation like a snifter can, and the tulip shape concentrates it. A similarly-sized and -shaped wine glass can work nearly as well.

While I enjoy stemware like this, as always my advice is to use whatever you like. As far as I’m concerned, if you don’t have to slurp your beverage directly off the counter you’re good to go.

Find out more about brandy by listening to the Winervana Podcast Episode 10 – Brandy, Cognac, and Armagnac.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

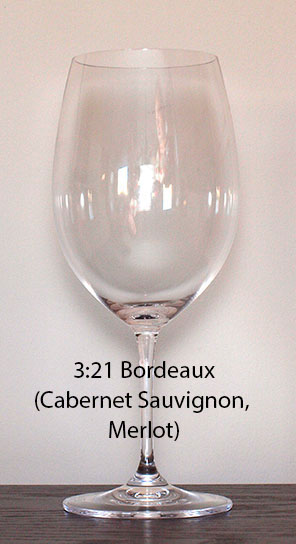

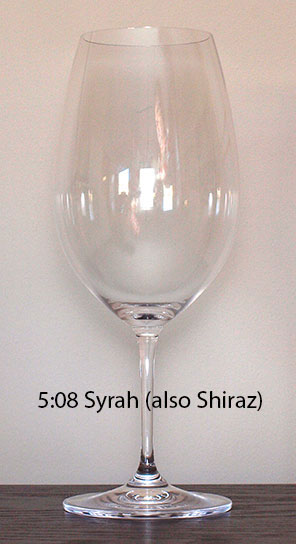

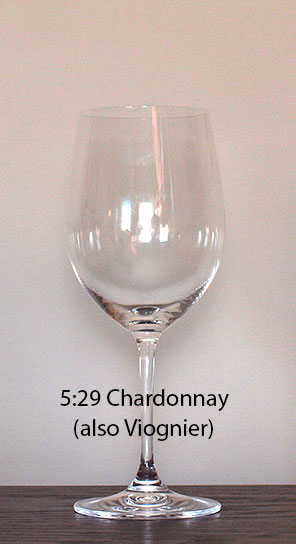

Established in Bohemia in 1756, Riedel (REE-dəl) Crystal is a glassware manufacturer based in Kufstein, Austria. Riedel was an early pioneer and proponent of glassware designed to enhance different varietals of wines. In the early 1990s, wine writer Robert Parker of the Wine Advocate became a major fan and proselytizer. The glasses below are the ones I own and discuss in my podcast on stemware (these are from Riedel’s Vinum line). If you are interested in Riedel but think this is overkill, I suggest you go with the Bordeaux and Chardonnay. Those two glasses should accommodate about 85% of your needs.

Read about Riedel’s in-depth explanation of why different glasses matter here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although, like Parker and many others, I am a fan of Riedel, not everyone agrees. In 2004, Gourmet magazine reported that “Studies at major research centers in Europe and the U.S. suggest that Riedel’s claims are, scientifically, nonsense.” The article cites further evidence from Yale researcher Linda Bartoshuk, saying that the “tongue map,” claimed by Riedel as an important part of their research, does not exist. According to Bartoshuk, “Your brain doesn’t care where taste is coming from in your mouth … and researchers have known this for thirty years.” I leave it to you to decide for yourself.

Looking for something completely different? Here are some grape varieties and wines from around the world to consider to really shake up your drinking experience.

Charbono is a relatively obscure French variety, but today it is much more widely grown in Argentina, as well as Napa Valley. It is often mistaken for the more common Dolcetto grape, though genetic testing has proven that they are not related. This grape produces a dark wine that is high in both tannins and acidity.

Austria offers Gruner Veltliner, its most widely-planted varietal. Gruner’s naturally high acidity makes it one of the world’s best food wines, especially with spicy cuisine. It can be light and easy, or with lower yields and higher ripeness, it can burst with aromas of white flower and flavors of grapefruit, herbs, mineral, and fresh-ground white pepper. .

The Austrian red varietal Blaufränkisch has characteristics of both Pinot Noir and Syrah. (And it is sometimes incorrectly thought to be the same variety as Gamay.) The wines it produces are lighter-styled reds, usually with plenty of acidity. It is grown in Germany, as well, where it is usually called Lemberger.

Gewürztraminer is thought to have originated in Italy’s Alto Adige region, but is now mostly famously grown in Alsace, located between France and Germany. It is planted throughout other nations in Europe, as well as California, Oregon, Washington, and New Zealand. These highly fragrant and crisp wines have flavors of spices such as clove, nutmeg, and lychee. You should drink a Gewürztraminer when young; they won’t last past five years.

Picpoul is normally grown in the Languedoc-Roussillon region of France, but is also sometimes grown in Spain. It is notable for its strikingly high acidity. One reason this grape isn’t as well known as others is because it is much more likely to develop a certain kind of fungus, making it more difficult to grow. There are three varieties of Picpoul: Picpoul Noir, Picpoul Gris, and the most well-known variety, Picpoul Blanc. Piquepoul Blanc is used both for blending and for varietal wines. Red wines produced from Picpoul Noir are high in alcohol, are richly scented, but have a very pale color, which has made the variety more popular as a blending ingredient than as a producer of varietal wines.

Valdiguié also hails from the Languedoc-Roussillon region. In the 1980s, this grape experienced a boom in Napa Valley, but poor cultivation and problems with disease quickly ended that. However, recently some intrepid wine makers in the United States have been trying to save Valdiguié’s tarnished reputation. When properly cultivated and prepared, Valdiguié is a unique wine, one with distinct fruity notes and a sweet-and-sour flavor profile, with a notably low alcohol conent.

Vouvray is the largest white wine appellation of the Anjou-Saumur-Touraine region of the Loire Valley, known for its siliceous-clay and limestone-clay soils and cool climate. The wine is made from the Chenin Blanc grape, grown in the region since the fourth century. It is capable of both dry wines and elegant sparklers. In years when botrytis cinerea, the mold responsible for sweet whites, hits, harvest is delayed in order to pick the grapes at their peak ripeness to produce a rich dessert wine.

Grown in Georgia (the country, not the state) the white varietal Rkatsiteli can drink like a Pinot Grigio. It’s also popping up in wines from New York’s Finger Lakes region, having been adopted and planted by the Dr. Konstantin Frank Winery there.

Mtsvane is like Sauvignon Blanc, but without the grassy notes that I find to be off-putting.

Kisi has been described as something between Chenin Blanc and Viognier on steroids.

Finally, Georgia’s Tavkveri is a workhorse, and the best examples are often vinified as light red wines (ala Beaujolais), with similar tangy, red-fruited, bright, and zesty characteristics.

Assyrtiko hails from the island of Santorini, where the volcanic soil produces juicy wines with good body and high acidity, great with South Asian food.

Malagousia is a rare variety grown mainly in Macedonia, with flavors of white peaches spritzed with jasmine.

Moschofilero, a pink/gray-skinned grape grown in central Peloponnese, has vibrant citrus acidity, attractive aromatics such as exotic spice and violet, and is often made as a Rosé.

Kourtaki Retsina of Attiki, the wine I like to call “The Greek Wine Even Greeks Won’t Drink.” The traditional grape for Retsina is Savatiano with Assyrtiko and Rhoditis sometimes blended in. Retsina is made like other white wines, but with the addition of small pieces of Aleppo pine resin being added during fermentation. It is this pine resin that gives Retsina its name, as well as its unique flavor profile. Read more about it here.

From Macedonia comes Xinomavro, Greece’s premier red grape, which typically shows characteristics of red fruit, sun-dried tomatoes, kalamata olives, and spices.

Egri Bikaver (”Bull’s Blood of Eger”), is a vintage-dated red wine that is made mainly from the Kadarka grape. I’ve been drinking it for decades, and it is relatively widely available, but aside from Hungarians it seems as almost no one knows about it.

Sicily’s white Carricante is likened to cool-climate Chardonnays, and the red Nerello Mascalese, with its earthy, herbaceous, yet muscular notes echoes some of the wines of Burgundy.

Verdicchio is a white wine grape grown mainly in the Marches region. The wines made from it have a subtle greenish hue, are generally crisp and dry, and have a light but elegant aroma and flavors of minerals and lemon. Verdicchio traditionally comes in a green, two-handled urn-shaped bottle called an amphora.

Grapes such as Souzao and Touriga Nacional, traditionally used to make Port, can make a classic table wine, too, that tends to be juicy and unpretentious. They are drink-me-now wines, particularly those from Douro, which stretches across north-central Spain and Portugal.

Vinho Verde comes from Portugal’s largest designated growing region. The wines made from it are slightly effervescent, can be red or white, are fresh and fruity and are meant to be drunk while still young.

South Africa is famous for its Pinotage, but it’s an enthusiasm I don’t share. It was cultivated there in 1925 as a cross between Pinot Noir and Cinsaut. It typically produces deep red wines with flavors of smoke, bramble, and earth, sometimes with notes of bananas and tropical fruit.

Emerging recently is a new category called orange wine. While Rosé is made from red grapes with a little grape skin contact to impart a small amount of color, orange wine is made from white grapes with extended skin contact creating anywhere from a peach to orange to amber color. So, since orange wine is a “white wine” made in the style of a red, there is at least the potential for plenty of flavor.

Ice wine is a type of dessert wine produced from grapes that have frozen while still on the vine. The sugars and other dissolved solids do not freeze, but the water does, and this makes for a more concentrated juice, which is then pressed from the still-frozen grapes in unheated wineries. This is then fermented, resulting in a small amount of highly concentrated, very sweet wine with high acidity.

Ice wine production is risky (the frost may not come at all before the grapes rot or are otherwise lost) and requires the availability of a large enough labor force to pick the whole crop within a few hours, at a moment’s notice, on the first morning that is cold enough. This low yield both in the field and in the winery makes them generally expensive. Canada is the largest producer, followed by Germany. There are also ice wine producers in the Niagara region of New York.

The Rapazzini Winery of Gilroy, California, “Garlic Capital of the World,” makes four garlic-infused wines, two reds and two whites. British wine expert Oz Clarke once braved one of the garlic white wines, describing it as an “unholy alliance of flavors.” Not a fan, apparently.

Winemaker Ian Hutcheon runs Tremonte Vineyard in Chile, as well as an astronomy center there. He has played off of that theme for a number of his wines. He has installed a “wave room” at his observatory which captures cosmic power from outer space that is then converted into audio. He claims that these sound waves trigger a structural molecular change in the wine stored in bottles and black oak barrels in the room. “The sound is eerie, and tourists state that they feel goose-pimples and even energized as they sip their cosmic wines while huge images of Galileo, Newton, and Einstein observe them from the dark,” said Hutcheon.

In 2012, Hutcheon produced Sacrificio wine, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Carmenere, and Syrah aged in French oak barrels for 12 months. These were then buried at the summit of Mount Tunca (in Australia, a long way to send the wine) and left to the elements for an entire winter. Tourists wanting to try the Sacrficio wine had to climb the mountain and locate the wine using a map.

Also in 2012, Hutcheon produced a Cabernet Sauvignon wine called Meteorito, which was aged with a chunk of a 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite placed into the barrel. “The meteorite used in the creation of this wine came from the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter,” he explained. “And the idea behind submerging it in wine was to give everybody the opportunity to touch something from space, an extra-terrestrial rock, the very history of the solar system, and feel it via a grand wine.” Ahem.

In western Massachusetts, Vermont, Nova Scotia, and other spots in North America’s “maple belt,” farmers sometimes blend grape wines with maple syrup or ferment straight-up maple sap. The sweet result works well as a dessert wine.

And, there are wines that aren’t made from grapes at all. If something has sugar in it, you can get alcohol out of it, and you can bet that someone has, or will, try that.

If some pumpkin-spiced booze appeals to you, California Fruit Wine Co. adds pumpkin-pie spices to fermented pumpkin juice, creating a semi-sweet, fall-flavored beverage. Very big with Harry Potter fans, apparently.

Omerto, made in Quebec, Canada, relies on a secret family recipe for a pale-gold wine made from heirloom tomatoes. Winemaker Pascal Miche produces dry and sweet versions of this aperitif wine, comparing them to Sauvignon Blanc and white port. Unfortunately, you’ll have to go to Canada, Belgium, France, or Monaco to get it. The Florida Orange Groves Winery makes a spicier tomato wine, spiked with hot peppers.

Schnebly Redland’s Winery in Florida makes a wine from avocados. They peel and pit the fruit, then blend the flesh with water, sugar, and yeast before fermentation in stainless-steel vats. In addition to both dry and sweet all-avocado wines, they turn out blends made with coconut and guava.

How about wine made from grapefruit juice? Look to Florida once again, where juice from the state’s famous pink grapefruit gets aged for several months after fermentation to mellow its tart edge. I couldn’t find a commercial producer, but there are a number of DIY recipes on the Interwebs.

If you’re a fan of tropical-fruit aromas in your Chardonnay or Riesling, you could plunge into an all-mango wine. Several southern Florida wineries, as well as Island Mana on Kauai, Hawaii, make this sweet tipple.

And finally, North Dakota’s Maple River Winery makes a hard-to-find semi-sweet pink wine. It does not contain any grapes or grape juice, but is made with white and lavender lilac flowers, water, sugar, yeast, and “adjuncts” according to the producer. Whatever “adjuncts” are.

See, I told you this would be something completely different.

Return to blog posts: https://winervana.com/blog/

Summer is a little more than half over, and the long, hot days are waning away. Which is fine with me, but I’m in the minority, as I am every year. Regardless, there are two months of nice weather left in most of the country, which is plenty of time to get together outside, at six-feet apart, of course, with a few close friends and enjoy some white wine. There are many to choose from, and I’ll get to that next. But first, what you don’t want for summer quaffing is a rich, buttery selection like a highly-oaked Chardonnay. (And I say “highly-oaked,” because for me, I’ve never encountered an “over-oaked” Chard.

That being said, here are eleven ABC (Anything But Chardonnay) grape variety suggestions for summer sippers, with some specific label recommendations as well.

1. Aligoté is the other white grape of Burgundy. The wines made from it are often citrusy and sometimes nutty. Try them while you can, because vineyards are being replanted to the much more popular Chardonnay all the time. One such is the Didier Montchovet Aligoté, which is fermented in enamel-lined tanks, rather than stainless steel. The wine is somewhat vegetal, with plenty of acidity.

2. Although justly famous for its Port dessert wine, Portugal isn’t a one-trick wine country. Its Alvarinho is from the Vinho Verde region. This thick-skinned grape produces wines of creamy richness, with apricots, peaches, and citrus flavors. The Reguengo de Melgaco expression is fresh and stony, with the typical citrus and some more exotic fruit. Once you cross the border into Spain, Alvarinho becomes Albariño. You could try the bright, fresh Salneval with its stone fruit and citrus, the refreshing Condes de Albarei that delivers stone fruit, melon, and actual stones, or the racy Brandal offering citrus, tangerine, and plenty of minerals.

3. Opa! Assyrtico from the Greek island of Santorini has citrus and honeysuckle flavors and a penetrating acidity. The Chatzivariti Eurynome has a nose of white flowers and that typical citrus, joined by minerals and spice on the palate. Or consider the Thalassitis, with its minerality and racy acidity supported by subtle lemon, spices, and herbs.

4. Italy’s Soave is famously made from Garganega. When carefully made, this grape can yield wines that are quite elegant, and exhibit a notable almond character. The I Masieri from Angiolino Maule is light and fresh, with plenty of mineral-laden tangerine, lemon, and grapefruit.

5. Known for its often high alcohol and low acidity, Grenache Blanc is widely planted in Spain and France, but this Acquiesce version comes from Lodi. It has a nose of pear, honey, and wildflowers, followed by flavors of honeysuckle, tropical fruit, and minerals.

6. Gruner Veitliner is a white wine grape grown mainly in Austria, but is also cultivated in parts of eastern Europe. The wines are pale, crisp, light-to-medium bodied, and often come with subtle spice notes. A sparkling example to try is Schlumberger Gruner Veitliner Klassik. This wine is a bright yellow, with hints of green and a nice fizz. If you’d prefer a still wine, there is the bright and crisp Loimer Lois [loyce].

7. Although it originated in Burgundy, Melon de Bourgogne [boor-gwan-yuh] now almost exclusively makes its home in the Loire Valley, where it is also known as Muscadet if it comes from the Pays Mantais subregion. Often aged sur lie (in which the wine has prolonged contact with dead yeast cells and other sediment to increase depth and complexity), these wines can be soft and creamy with hints of citrus. The light-bodied expression from Marc Presnot, La Bohème, is all that, plus flowers, grapefruit, and figs. The bone-dry Henri Poiron Domaine des Quatres Routes has a nose of green apple and pineapple. More green apple pairs with lemon peel on the palate.

8. I like Pinot Grigio (also known as Pinot Gris depending on where it’s grown), but I just can’t get excited about it. Dunno why. Regardless, this grape can range from crisp, light and dry when it’s made in northern Italy, to rich, fat, and honeyed Alsacian versions. Predictably, the Luna Nuda from Alto Adige is bright and fresh, with citrus, apples, and minerals dominant. The widely available Lindeman’s Bin 85 from Down Under has citrus, white stone fruit, and some grassy notes. The high acidity makes it quite refreshing. Left Coast Cellar‘s The Orchards hails from Willamette, and offers up light citrus and a hint of flowers. The medium body has a creamy texture and medium acidity.

9. OK. Riesling. I’m going to be honest about this up-front: although Riesling is, by all accounts, one of the world’s greatest white-wine grapes, and makes classic food-friendly wines in a range of styles from quite dry to very sweet, I’ve never been much of a fan. This baffled me for a long time, but I finally figured it out. I find that most Rieslings exhibit both an aroma and a taste of oil. At their best, it’s like olive oil. At their worst, it’s like motor oil, at least to me. Once you get beyond that, they have zippy acidity, notes of spice and fruit (particularly peaches and apricots), and a flower-scented bouquet. A good German expression to try would be Armand Riesling Kabinett, which has that characteristic spice, fruit, and acid, plus a bit of sweetness. Another is the Schloss Schonborn Marcobrunn, an elegant wine with aromas of apricot, peach, and tangerine, balanced by minerality and hints of spice. Plenty of Riesling comes from California, too. Ser Dry Riesling, produced near Santa Cruz, tastes of mostly tart citrus, particularly lime, with subtle hints of pear and apple. (You can read more about Ser here.) The off-dry and medium-bodied J. Lohr Bay Mist entices with honeysuckle, spice, and a lush mouthfeel, accompanied by tropical fruit and pear. And there is the typically dry Gobelsburger from Austria, featuring white peach, nectarine, apricot, and a bit of pepper. Finally, the Jacob’s Creek Reserve from Australia is easy-drinking, crisp, and packed with juicy citrus.

10. Roussanne hails from France’s Rhône region, and its wines are often delicate and refined. But these two are from California. The Edmunds St John from Paso Robles offers an oily texture, tastes of mangoes, baking spices, and honey, all balanced by a vibrant acidity. The always reliable Cline in Sonoma makes a blend of Marsanne and Roussanne that has notes of honey, orange, and pineapple with a mineral finish. It is completely unoaked.

11. Probably the best well-known of these varietals to most people, Sauvignon Blanc is widely grown around the world, with France, California, and New Zealand being major producers. Sauvignon Blancs can show plenty of acidity and minerality, so they are crisp and flavorful, and best when young. This all makes them classic summer wines. They can also have grassy and herbaceous flavors and aromas. These don’t appeal to me, but many others enjoy those sorts of things. Rombauer comes from Napa Valley. This is the same family responsible for The Joy of Cooking. This refreshing wine delivers flavors of grapefruit, lime, and white peach, with just a smidgen of grass. Riley’s Rows is owned by a young vintner in Sonoma who is just 20 years old and is still in college! Her wine is nearly colorless, and has a delicate nose of papaya and honeydew. It is slightly sweet, with subtle flavors of lemon and grapefruit, and absolutely no grassiness. From New Zealand I have three possibilities: there is te Pa, with gooseberry and nectarine on the palate, ending in mineral and flint notes. The international powerhouse Kim Crawford is readily available. It offers a tart, refreshing, distinct grapefruit nose and taste. It is completely dry, with a bit of flint on the finish. Whitehaven is a small producer, so it may be harder to find. Their wine is medium bodied, with blackcurrant and gooseberry flavors and a dry, clean finish. And I can suggest the Bird in Hand Sauvignon Blanc from Australia for its flavors of gooseberry and passionfruit and a bit of lemon curd.

Many of these wines share traits of citrus, minerality, and crisp acidity. If you seek out selections for summer sipping with these same characteristics, you really can’t go wrong.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

From left to right: Lubanzi (photo courtesy of Lubanzi), Underwood (photo by Jules Davis), and Alloy (photo courtesy of Alloy)

When it comes to wine packaging, the glass bottle has been the primary choice for centuries. Because of this long history and tradition, consumers associate the bottle size, shape, and color directly with the quality of the product within. By and large, screw-top closures, oddly-shaped bottles, non-glass containers, and boxes were relegated to lower-quality products.

That all began to change about 20 years ago, with a growing acceptance of screw-tops, the ones from Swiss company STELVIN® in particular. It is an aluminum closure system specially designed for wine, featuring a specific bottle neck finish and a range of liners. This was accompanied by the wide introduction of packaging alternatives such as Tetra Paks, wine-on-tap, bag-in-box, individual-serving sized plastic pouches, and aluminum cans.

A short history of canned wine

A short history of canned wineThe story of canned wine, particularly, is much older, however. In the mid-1930s, metal-canning technology was developed, and people have been consuming assorted beverages, such as soda, juice, and beer in cans for over 90 years, of course. As early as 1936, the Acampo Winery began packaging a California Muscatel in steel cans under its Acampa brand. Another early pioneer was Vin-Tin-Age. (You’ve got to love that forced pun. Or not.) However, these early efforts failed with drinkers, presumably due to the wine’s interaction with the unlined metal of the steel can. In the early ’80s there was another attempt to sell wine in cans, this time made of aluminum. Taylor California Cellars tried to convince airlines to serve their wine in lightweight, single-serve aluminum cans. However, small glass and/or plastic packaging won out instead; the now-ubiquitous 50 ml airplane bottle is familiar to anyone who has flown, or visited a liquor store.

Regardless of specific type, any wine packaging must serve three purposes. First, it must to protect the wine, which can be damaged if exposed to oxygen, bacteria, or other harmful contaminants. Second, it must contain the wine (duh!), allowing it to be transported, stored, and consumed. Finally, it must provide information about what you’re drinking: where the grapes were grown, the alcohol percentage (ABV), the name of the wine, and more. Cans do a excellent job of protecting wine, especially ones that are young, fresh, and fruity, with little to no oak contact, low to moderate tannins, and intended for consumption shortly after purchase.

Canned wine accounts for a tiny fraction of the market, about one percent. Even so, cans are one of the fastest-growing forms of alternative wine packaging. For years, a can was seen mainly as a convenient way to deliver cheap wine, but these days the same change in consumer acceptance that occurred with screw-caps is happening with canned wine, with higher-quality wines being introduced over the last two decades. Wine-in-can sales totaled $6.4 million in 2015, $14.5 million in 2016, and $22.3 million in 2017. In 2018, sales jumped to more than $69 million, totaling the equivalent of 739,000 12-bottle cases in retail outlets tracked by Nielsen. That’s up from just $2 million in 2012, compared with a five-percent increase in boxed wines and a 14.2-percent gain for wine in Tetra Paks during the same period.

A number of factors have contributed to wineries’ enthusiasm for canned wine. Cans offer drinkers convenience and portability, since cans are welcome many places glass bottles are not, such as private lawns and pools. The labeling is often fun, dramatic, and creative, allowing producers to position themselves as modern and forward thinking, which is of particular importance to Gen Zers and Millenials. Gotta stay hip, ya know. More substantially, aluminum is 100% recyclable, resulting in a very small environmental footprint. Due to lighter weight during shipping and handling, reduced breakage, and more-efficient stacking, cans versus glass bottles also yield typical savings to producers of approximately 15 to 20%, with some claiming as high as 40%.

Another detail not to be overlooked is the lining that coats the inside of the can, and prevents the liquid from interacting with the aluminum, which was the bane of the false starts of years ago. The pioneer in this regard is the Baroke Winery of Australia. In 1996 they introduced their patented can-coating system, trademarked as Vinsafe. However, no U.S. producers use the Vinsafe technology, relying instead on coatings developed by domestic can makers, primarily Ball. Note that because wine is acidic (less so than beer, more so than cola), eventually the polymer coating can degrade. Another reason to enjoy canned wine as soon as possible (as if we need one).

Finally, we must not disregard the impact of the Internet. It is full of selfies of consumers with colorful, creative cans. The fun and festive nature of many of the designer cans inspires social media blog entries, hashtags, and pictures of friends enjoying the wine together as well.

Currently, 350 wine-in-a-can products are available from 125 wineries in 13 countries. In Japan, wine in cans is very popular, in part because selections are widely available in vending machines. (This is a convenience that will likely never be seen in the U.S. market, due to our century-old hangover from Prohibition.) Quite a number of canned sakés are also offered there.

In the U.S., Francis Ford Coppola (yes, the director of the Godfather trilogy and Apocalypse Now, as well as many other films) recreated the wine-in-can category in 2002 by producing a wine named after his daughter, Sofia, to serve at her pool-side wedding. He also cans his Diamond brand. Since then, Coppola has been joined by such major producers as E. & J. Gallo with their Barefoot and Dark Horse labels; The Infinite Monkey Theorem of Colorado and Texas; Precept Wine conglomerate’s House brand; Field Recordings / Alloy Wine Works offering California selections; and Union Wine Company of Oregon which sells its products under the Underwood label.

Andrew Jones founded Field Recordings, a single-vineyard project, in Paso Robles, California, in 2007. Jones released his first canned wine, Fiction Red, under the Alloy Wine Works label (Get it? Metal? Alloy?) in 2014. It was intended as a one-off release, but the positive response from buyers prompted him to pursue the format; today, around 40% of the winery’s production is canned. The lineup consists of three core wines: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Everyday Rosé. In addition, they frequently release unorthodox, limited-edition offerings, mainly for the can-wine club members, though they sometimes become permanent additions to the portfolio. “It was about meeting people where they wanted to be,” says Jones. “They wanted top-quality, terroir-driven grapes, treated the same way they would be for the bottle, but in a smaller, endlessly recyclable package that could be consumed anywhere.” Jones sold the company to Vintage Wine Estates in 2019, but is still involved. He reports that his production line is currently 20 times what it was when he launched.

Union Wine Company dove into canning by launching its Underwood label in 2014, relying on 375 ml cans. Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris were the first two varietals offered, but the lineup has since expanded to include still rosé, white and rosé sparkling wines, a white blend, and wine coolers. Today, 55% of the company’s 448,000-case business is in cans, up a remarkable jump from just over 100,000 cases in 2014.

Founder and owner Ryan Harms credits the success of Underwood’s canned products to their affordability and lack of pretension. “With cans, we embrace the artistry of making great wine, minus all the fuss,” Harms says. “And we’ve remained committed to our original mission of bringing craft quality and affordable Oregon wines to people’s tables for everyday occasions.” Harms says the appeal of the Underwood wines is that they have “an implied ‘ready to drink’ quality, which allows them to lend themselves to the can better than other styles might.”

Most canned wines are either 375 ml (a half “bottle” of wine) or 250 ml (the size of a can of Red Bull). While the 375s can be sold individually, the federal government prohibits individual sales of the 250 ml cans, requiring that they be sold in four-packs. I prefer the 375 ml size when I can get it. Some wines come in 187 ml or 500 ml cans, but these are less common. And, an individual winery won’t offer a variety of can sizes; they pick one and stick with it.

I can recommend just about all of the Underwoods, especially The Bubbles, Dark Horse Rosé, Butter Chardonnay (even though its oaked profile is atypical of canned wine), Creamery Chardonnay, and Cupcake Chardonnay.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/