Orin Swift Cellars was a relative newcomer on the California wine scene, having been established in 1998, but not by “Orin Swift,” as I had long assumed. Rather, it was by the now iconic, and iconoclastic, winemaker David Phinney. Orin is Phinney’s father’s middle name and Swift is his mother’s maiden name.

Phinney, a native Californian, was born in Gilroy (the “Garlic Capitol of the World”), the son of a botanist and a college professor. However, within a week he was in Los Angeles, where he spent his childhood, and finally an adolescence in Squaw Valley. He enrolled in the Political Science program at the University of Arizona, with an eye towards a law degree, but before long became disillusioned with both. At this juncture, a friend invited him on a trip to Italy, and while in Florence he was introduced to the joys of wine, and soon became obsessed.

Back in the States, he began his career by working the night-shift harvest at Robert Mondavi in 1997. Encouraged by Mondavi, remarkably he started his own Napa Valley brand the very next year with the purchase two tons of some Zinfandel, though he wasn’t sure what he was going to do with it. Predictably, there were some false starts. Orin Swift’s first vintage was okay but not noteworthy, with Phinney confessing that he made an error in sourcing average fruit from the ‘wrong part’ of a great vineyard. Eventually he figured it out though, creating a rich, seductive, runaway best-selling wine called The Prisoner (an unusual blend of Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Petite Sirah, and Charbono).

Since making his first wine in 1998, Phinney has been guided by two criteria: “find the best fruit from the best vineyards and don’t screw it up” and if you do screw it up “experience is what you get when you don’t get what you want.”

David Phinney. Photo: Margaret Pattillo.

In a controversial move in 2016, E&J Gallo (yes, that Gallo) acquired Orin Swift for nearly 300 million dollars, but Phinney shrewdly negotiated to remain in charge of production and winemaking for them. “I have access to their amazing vineyards; after the harvest in 2016 – the first year – I threw a barbeque for all the rest of the [Gallo] winemakers, some who I knew, some I didn’t, to apologize for stealing their grapes because I knew we were getting access to stuff we probably shouldn’t have!” Orin Swift Cellars has since been renamed The Prisoner Wine Company.

While some observers saw it as a canny and natural business move, there were also whispers of criticism about Phinney ‘selling out.’ He is sensitive to the complaint, but stands by his decision. “It was a very natural, organic coming together, I’ve known and worked with the Gallos since 2005 and it was just kind of a conversation that was spurred because our growth curve was like a hockey stick, and that’s when you become attractive to bigger wineries,” he says.

Such financial independence has allowed Phinney to also produce wines from vineyards he owns in California and four European countries (France, Italy, Spain, Greece).

Many of the wines Phinney makes are blends. This is by design and not circumstance, so having access to a huge number of vineyards and parcels in sought-after areas of Napa Valley and beyond makes his job more interesting, and his quest for producing great wines arguably easier, as he is always striving for balance in his products. “For me the easiest way to achieve complexity is through geographic diversification, and that can be county-wise, valley-wise, country-wise,” he says. “I was told many years ago, and I believe it, that if you put a lot of good red wine together you often make a great red wine, so having that – and I hate this phrase – ‘spice rack’ of different things to play with can really work. You still have to be a custodian of each wine so that when you add them together the finished wine is better than the sum of its parts, that’s where I think blending really works.” And although he admits it’s a cliché, he believes that 90% of a wine is made in the field, so vineyard selection is the key to success.

Phinney also creates all the of the wine labels, and he is always looking for inspiration, much of which comes from his extensive travels around the world. “They all start and end with me, whether I like it or not. I grew up in LA in the 1980s very much in the punk/skateboarding/surfing scene, so there’s definitely a street art aspect to it. The flipside of that is that my parents were both professors, so we basically travelled the world and wherever we went we always had to go to a fine art museum. So there’s always been this relationship with art either by proxy or by design.”

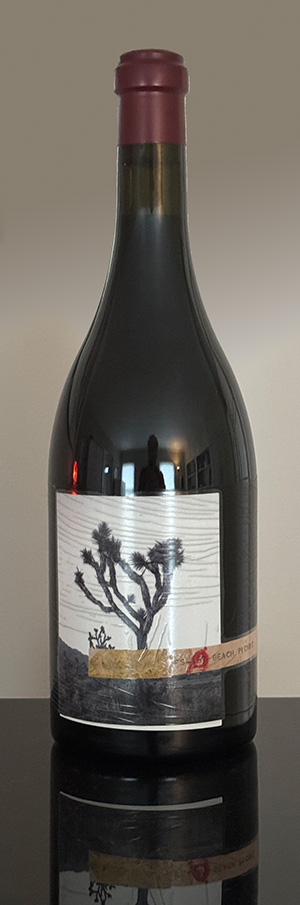

Eight Years in the Desert 2022

Unusual name, no? Before the acquisition by Gallo, in 2008 Phinney sold Orin Swift to Huneeus Vintners, makers of Quintessa and six other labels. The sale came with an eight-year non-compete agreement, preventing him from producing Zinfandel blends under the Orin Swift brand. This wine, first released in 2016, celebrates his return to Zinfandel. A blend of Zin, Syrah, and Petite Sirah, it was aged for six months in French oak, 32% new, and is a nice transparent garnet. The nose offers up aromas of cherry and a bit of dust, but in a good way. The palate features tart cherry, ripe plum, black raspberry, and graphite. There are plenty of well-integrated tannins, and it ends in a long finish. The ABV is a robust 15.6%.

I’m not decanting as often as I used to, but this wine benefits from about 45 minutes of air. I much preferred Eight Years in the Desert and the 2018 Orin Swift Palermo to the more famous and popular The Prisoner. YMMV.

Note: This selection is guilty of Bloated Bottle Syndrome, which I’m calling out for bottles that weigh more than the wine they contain. The web site of nearly every winery will usually include a mention of the operation’s dedication to “sustainability” and “stewardship.” Unfortunately, this often seems only to extend to the property itself. Many “premium” wines like this one come in heavier bottles to allegedly denote quality. This one weighs in at 880 grams. (As an example of a more typical bottle, Estancia Cabernet’s comes in at 494 grams.) That’s a lot of extra weight to be shipping around the country (or the world). By comparison, the wine inside, as always, only weighs 750 grams. Even sparkling wine bottles are often about the weight of this one, and those are made to withstand high internal pressure. Unfortunately, this sort of “bottle-weight marketing” is becoming more common, especially at higher price points. But there are other ways to denote quality without weight: unusual label designs, foils, wax dipping, etc.

Plastic bottles have a lower environmental impact than glass, 20% to 40% less, in fact. And, bag-in-box packages are even less than plastic bottles. (Unfortunately, current bag technology will only keep unopened wine fresh for about a year, so they are only suitable for wines to be consumed upon release from the winery; that’s about 90% of all wine sold though.)

The carbon footprint of global winemaking and global wine consumption is nothing to scoff at, amounting to hundreds of thousands of tons per year. The latter, which requires cases of wine be shipped around the world, imprints a deep carbon footprint. Because wine is so region-specific, and only so many regions can create drinkable bottles, ground and air transportation is responsible for nearly all of the wine industry’s greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Sustainable Wine Roundtable, a group of wineries, retailers, and other companies connected to the wine industry, one-third to one-half of that total is due to the glass bottles themselves.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/