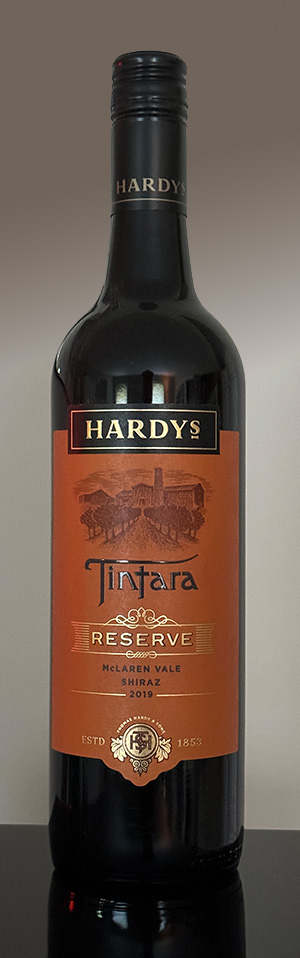

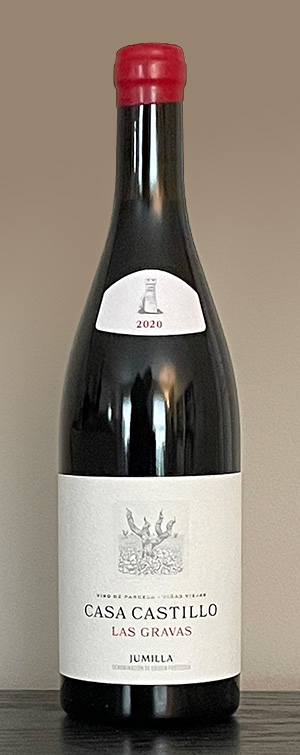

The Jumilla DO [Denomination of Origin] is located in the Levante region of eastern Spain, about 60 miles west of the coastal town of Alicante. With over 100,00 vineyard acres, the area has long been associated with big, high alcohol red wines. The sun-baked landscape sees 300 days of sunshine per year and a low amount of rainfall. But the soils are very good: deep, not very compact, and with great water retention potential.

Since 1991 José María Vicente has been the third-generation owner and operator of the Casa Castillo winery. When his grandfather bought the estate in 1941, situated on the slopes of the Sierra del Molar, the property had an existing winery, a cellar built by Frenchmen fleeing the phylloxera plague in 1870, and a few scattered vineyards.

Originally Casa Castillo was a farm growing wild rosemary, and became an estate producing rather ordinary grapes for local wineries. On his first visit to France, including the whole area of the southern Rhone, Vicente was surprised to see that Monastrell, called Mourvedre there, was considered a very noble variety with great aging potential. This led him to reconsider the supposed “improving varieties” that he was planning on planting to help give a supposed complexity to the Monastrell at Casa Castillo, and instead focus entirely on the study and development of that varietal as the true protagonist of his wines. Continue reading “Casa Castillo Las Gravas 2020”

You could spend $100 on this incredibly sweet tequila. Or, you could buy a bottle of agave syrup for $5 and a mid-range Blanco tequila for $20, mix them, and get basically the same result. I got through the bottle by making Millionaire’s Margaritas, which were actually pretty tasty.

You could spend $100 on this incredibly sweet tequila. Or, you could buy a bottle of agave syrup for $5 and a mid-range Blanco tequila for $20, mix them, and get basically the same result. I got through the bottle by making Millionaire’s Margaritas, which were actually pretty tasty.