Freemark Abbey Cabernet Sauvignon Oakville 2017

In 1881, Josephine Marlin Tychson and her Danish husband, John, traveled from Pennsylvania to St. Helena in the hope of alleviating his tuberculosis and becoming vintners. They purchased 147 acres of property just north of town from a retired sea captain, William Sayward, who had earlier bought the land from Charles Krug. They planted Zinfandel, Riesling, and “Burgundy” vines on the estate. Five years later, Tychson Cellars was established, but not before John’s despair over his affliction caused him to kill himself.

After this sad event, the undaunted Josephine continued to nurture the vines she and her husband had planted together, and with the help of her foreman, Nils Larsen, she oversaw the construction of an impressive redwood winery, large enough to contain up to 30,000 gallons of wine. She became the first woman in the entire state of California to oversee the building of a winery and one of the first few female winemakers in the state.

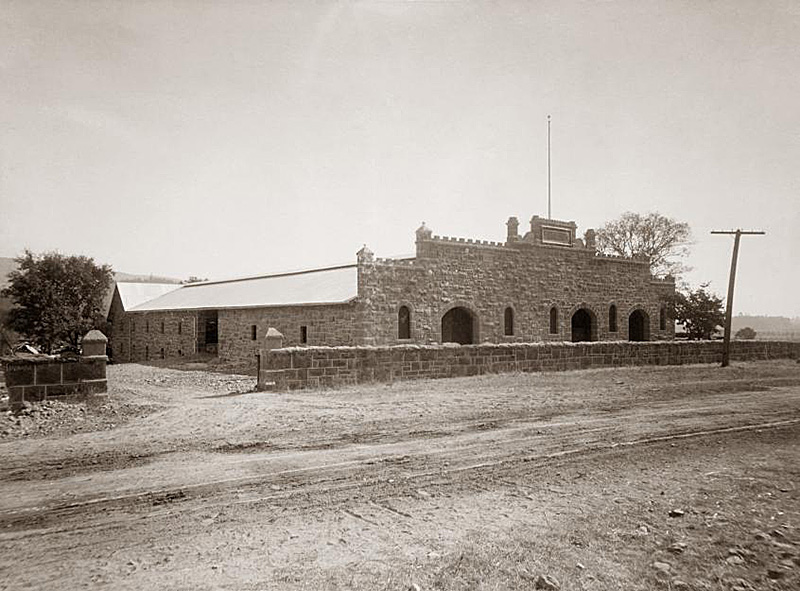

However, her stewardship only lasted until 1894, when she sold the facility to Larsen. He in turn leased the property to Italian immigrant Antonio Forni and sold it to him in 1898. Forni renamed the winery Lombarda Cellars after his birthplace in Italy, and the following year he razed Tychson’s winery and constructed a new building out of hand-hewn stones from nearby Glass Mountain. Workers were primarily Italian; many of their descendants live in St. Helena to this day. This historic winery structure was until fairly recently used for barrel storage and wine making, but both have since been moved off site. All wines are now made at Cardinale Winery in Oakville, part of Jackson Family Wines, the current owner of Freemark.

Forni concentrated his efforts on making Chianti and other Italian-style wines which he marketed to the numerous Italians that had moved to Barre, Vermont, the site of America’s largest marble and granite quarries. Like so many others, Forni was forced to cease most operations when Prohibition began in 1920. He was licensed to produce sacramental wine for the Catholic Church, but that barely kept the operation viable.

Forni, who never fully recovered from Prohibition, sold the winery and vineyard in 1939 to three businessmen from Southern California, Albert “Abbey” Ahern, Charles Freeman, and Markquand Foster. They renamed the winery Freemark Abbey. (Amusingly, despite the sacramental wine production history, the winery has never been part of a monastery or a religious body; the name is instead a combination which includes a portion of each partner’s name.) The winery opened a “sampling room” in 1949, making this one of the first tasting rooms in Napa Valley. (Incidentally in the 1950s Freemark Abbey was one of the largest up-valley wine grape jelly producers. An article from the September 10, 1952 issue of the Napa Register references at least twelve different types of jellies produced at the winery that year.)

During the 1940s and 1950s the partners sold the majority of their wines to retail outlets in and around San Francisco, but the operation once again fell on hard times and Freemark Abbey was shuttered from 1959 until 1966. That year, a new partnership of seven businessmen led by Charles “Chuck” Carpy, whose grandfather had been one of the founders of Christian Brothers, purchased the fallow Freemark Abbey property and immediately ramped up both its production and reputation, mainly with its Napa Valley Cabernet. They owned the winery until 2001 when it was sold to The Legacy Estate Group. In March 2005 Legacy Estate overreached and tried to consolidate Arrowood and Byron into one conglomerate with Freemark. Eight months later, in November 2005, Legacy Estate went bankrupt, and was acquired by Jackson Family Wines.

The Judgment of Paris was organized in 1976 by Steven Spurrier, a British wine merchant, and his colleague, Patricia Gallagher, which put California wine on the international stage when its wines were pitted against several top red Bordeaux and white Burgundy producers in a blind tasting competition in France. Freemark Abbey was the only California winery to have both a white wine and a red wine entered. When the results came in, the 1972 Freemark Chardonnay (labeled Pinot Chardonnay as Chardonnay was commonly, but oddly, called during those days) placed sixth, ahead of both grand cru and premier cru Burgundy Chardonnays. Even more shockingly, Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars won first place for the reds, and Chateau Montelena for the whites, both from California. The wine world was forever changed. Rematches were held in both 1986 and 2006, with California wines once again taking top honors.

For a winery with such a long history, it is interesting to note that Freemark Abbey does not directly own the vast majority of the vineyards they work with in Napa Valley – rather they purchase fruit from other growers. With that said, they have established long-term relationships with select growers in the valley and several of their wines are from vineyards they have been sourcing from for many years. Their total production each year is around 60,000 cases with the majority of that for one wine – their Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon.

Freemark Abbey Cabernet Sauvignon Oakville 2017

This nearly opaque, dark red selection has a nose of dark berries, with a hint of leather. The flavors are dominated by tart cherry, which is somewhat recessive. They are supported by grippy tannins and good acidity. There is also a bit of earth on the medium body, and it finishes nicely long. ABV is 14.2%.

Note: This selection is guilty of Bloated Bottle Syndrome, which I’m calling out for bottles that weigh more than the wine they contain. The web site of nearly every winery will usually include a mention of the operation’s dedication to “sustainability” and “stewardship.” Unfortunately, this often seems only to extend to the property itself. Many “premium” wines like this one come in heavier bottles to allegedly denote quality. This one weighs in at a hefty 876 grams. (As an example of a more typical bottle, Estancia Cabernet’s comes in at 494 grams.) That’s a lot of extra weight to be shipping around the country. By comparison, the wine inside, as always, only weighs 750 grams. Even sparkling wine bottles often weigh less than this one, and those are made to withstand high internal pressure. Unfortunately, this sort of “bottle-weight marketing” is becoming more common, especially at higher price points. But there are other ways to denote quality without weight: unusual label designs, foils, wax dipping, etc.

Plastic bottles have a lower environmental impact than glass, 20% to 40% less, in fact. And, bag-in-box packages are even less than plastic bottles. (Unfortunately, current bag technology will only keep unopened wine fresh for about a year, so they are only suitable for wines to be consumed upon release from the winery; that’s about 90% of all wine sold though.)

The carbon footprint of global winemaking and global wine consumption is nothing to scoff at. The latter, which requires cases of wine be shipped around the world, imprints a deep carbon footprint. Because wine is so region-specific, and only so many regions can create drinkable bottles, ground and air transportation is responsible for nearly all of the wine industry’s CO2 emissions.

Back to blog posts: winervana.com/blog/

One Reply to “Freemark Abbey Cabernet Sauvignon”