In 1881, Josephine Marlin Tychson and her Danish husband, John, traveled from Pennsylvania to St. Helena in the hope of alleviating his tuberculosis and becoming vintners. They purchased 147 acres of property just north of town from a retired sea captain, William Sayward, who had earlier bought the land from Charles Krug. They planted Zinfandel, Riesling, and “Burgundy” vines on the estate. Five years later, Tychson Cellars was established, but not before John’s despair over his affliction caused him to commit suicide.

After this sad event, the undaunted Josephine continued to nurture the vines she and her husband had planted together, and with the help of her foreman, Nils Larsen, she oversaw the construction of an impressive redwood winery, large enough to contain up to 30,000 gallons of wine. She became the first woman in the entire state of California to oversee the building of a winery and one of the first few female winemakers in the state.

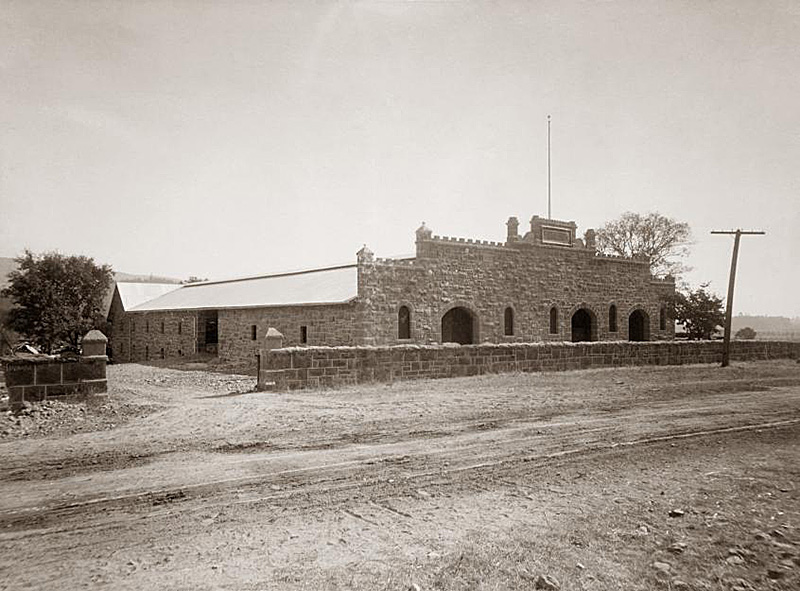

However, her stewardship only lasted until 1894, when she sold the facility to Larsen. He in turn leased the property to Italian immigrant Antonio Forni and sold it to him in 1898. Forni renamed the winery Lombarda Cellars after his birthplace in Italy, and the following year he razed Tychson’s winery and constructed a new building out of hand-hewn stones from nearby Glass Mountain. Workers were primarily Italian; many of their descendants live in St. Helena to this day. This historic winery structure was until fairly recently used for barrel storage and wine making, but both have since been moved off site. All wines are now made at Cardinale Winery in Oakville, part of Jackson Family Wines, the current owner of Freemark.

Forni concentrated his efforts on making Chianti and other Italian-style wines which he marketed to the numerous Italians that had moved to Barre, Vermont, the site of America’s largest marble and granite quarries. Like so many others, Forni was forced to cease most operations when Prohibition began in 1920. He was licensed to produce sacramental wine for the Catholic Church, but that barely kept the operation viable.

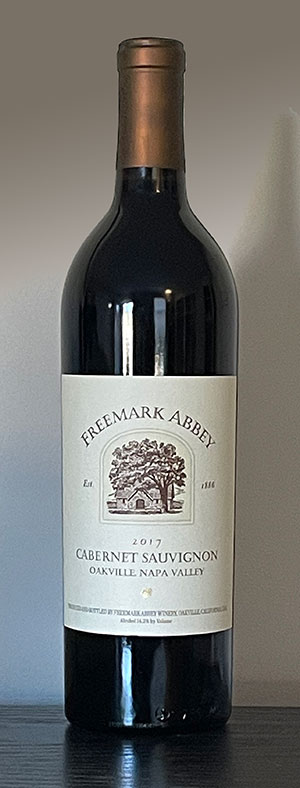

Forni, who never fully recovered from Prohibition, sold the winery and vineyard in 1939 to three businessmen from Southern California, Albert “Abbey” Ahern, Charles Freeman, and Markquand Foster. They renamed the winery Freemark Abbey. (Amusingly, despite the sacramental wine production history, the winery has never been part of a monastery or a religious body; the name is instead a combination which includes a portion of each partner’s name.) The winery opened a “sampling room” in 1949, making this one of the first tasting rooms in Napa Valley. (Incidentally in the 1950s Freemark Abbey was one of the largest up-valley wine grape jelly producers. An article from the September 10, 1952 issue of the Napa Register references at least twelve different types of jellies produced at the winery that year.) Continue reading “Freemark Abbey Cabernet Sauvignon Oakville 2017”

An American Viticultural Area, or AVA, is an American wine-growing region classification system inspired by the French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, or AOC, but without the French rigor. An AVA simply defines a geographic area, and omits grape varieties, maximum production per acre, alcohol levels, etc. The requirements for wine with an AVA designation is that 85 percent of the grapes used must be grown there, and the wine be fully finished within the state or one of the states in which the AVA is located. AVAs range in size from several hundred acres to several million; some reside within other larger AVAs.

An American Viticultural Area, or AVA, is an American wine-growing region classification system inspired by the French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, or AOC, but without the French rigor. An AVA simply defines a geographic area, and omits grape varieties, maximum production per acre, alcohol levels, etc. The requirements for wine with an AVA designation is that 85 percent of the grapes used must be grown there, and the wine be fully finished within the state or one of the states in which the AVA is located. AVAs range in size from several hundred acres to several million; some reside within other larger AVAs.

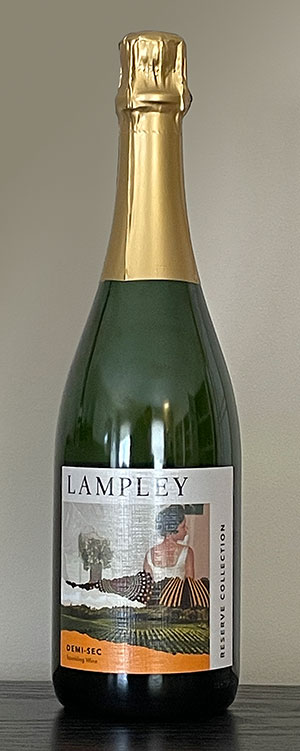

Nancy Tenuta is one of only six female winery owners in the

Nancy Tenuta is one of only six female winery owners in the  Nancy Tenuta graduated from Portland State University in 1981, and spent the next twenty years in the business world. She held a number of sales positions, and in the 1990s she traded stocks. Ron Tenuta was general manager of Protection Services Industries in Livermore, which specializes in commercial security.

Nancy Tenuta graduated from Portland State University in 1981, and spent the next twenty years in the business world. She held a number of sales positions, and in the 1990s she traded stocks. Ron Tenuta was general manager of Protection Services Industries in Livermore, which specializes in commercial security. An American Viticultural Area, or AVA, is an American wine-growing region classification system inspired by the French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, or AOC, but without the French rigor. An AVA simply defines a geographic area, and omits grape varieties, maximum production per acre, alcohol levels, etc. The requirements for wine with an AVA designation is that 85 percent of the grapes used must be grown there, and the wine be fully finished within the state (or one of the states) in which the AVA is located. AVAs range in size from several hundred acres to several million; some reside within other larger AVAs.

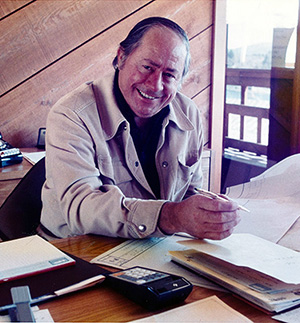

An American Viticultural Area, or AVA, is an American wine-growing region classification system inspired by the French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, or AOC, but without the French rigor. An AVA simply defines a geographic area, and omits grape varieties, maximum production per acre, alcohol levels, etc. The requirements for wine with an AVA designation is that 85 percent of the grapes used must be grown there, and the wine be fully finished within the state (or one of the states) in which the AVA is located. AVAs range in size from several hundred acres to several million; some reside within other larger AVAs. In the early 1970s, Joe Phelps started looking for a place to make a little wine. After a stint in the Navy, he’d grown his father’s Greeley, Colorado-based construction business into a multi-state powerhouse, expanding to northern California in the mid-1960s to work on bridge and dam projects and the infrastructure for BART. As a hobby, he did some home winemaking in Greeley using grapes shipped by air overnight from Napa. After landing the contract to build the Souverain Winery, the idea of starting his own winery took hold.

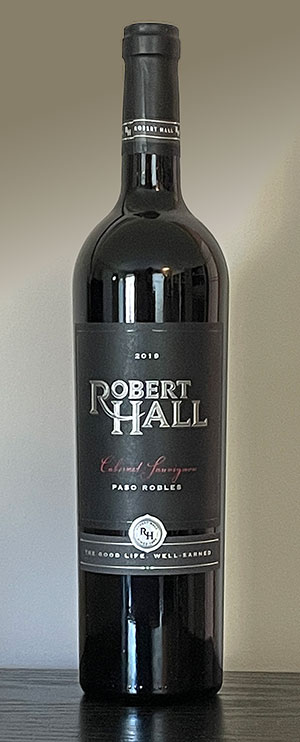

In the early 1970s, Joe Phelps started looking for a place to make a little wine. After a stint in the Navy, he’d grown his father’s Greeley, Colorado-based construction business into a multi-state powerhouse, expanding to northern California in the mid-1960s to work on bridge and dam projects and the infrastructure for BART. As a hobby, he did some home winemaking in Greeley using grapes shipped by air overnight from Napa. After landing the contract to build the Souverain Winery, the idea of starting his own winery took hold. Located 20 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco,

Located 20 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco,

A fifth-generation farmer, Vijay Reddy came to the U.S. in 1971 to pursue a graduate degree in soil and plant science, and obtained a doctorate in 1975 from Colorado State University. Along with his wife Subada, Dr. Reddy established and ran a soil consulting laboratory for 20 years while also farming cotton, peanuts, and various other produce in the high plains of west Texas near Lubbock (Reddy is a fifth-generation farmer).

A fifth-generation farmer, Vijay Reddy came to the U.S. in 1971 to pursue a graduate degree in soil and plant science, and obtained a doctorate in 1975 from Colorado State University. Along with his wife Subada, Dr. Reddy established and ran a soil consulting laboratory for 20 years while also farming cotton, peanuts, and various other produce in the high plains of west Texas near Lubbock (Reddy is a fifth-generation farmer).

True Ports (now often referred to as Portos) hail from the

True Ports (now often referred to as Portos) hail from the

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it’s a maxim Sosie Wines lives by. “Sosie” [so-zee] is French for twin or doppelganger, and as it says right on the bottle, “We are inspired by the wines of France. So we employ an Old World approach to wine growing that favors restraint over ripeness, finesse over flamboyance. Our aim is to craft wines that show a kinship with France’s benchmark regions. Wines that are their sosie.”

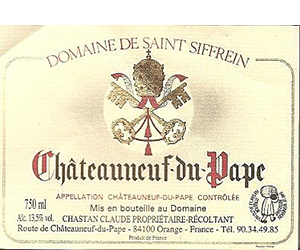

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it’s a maxim Sosie Wines lives by. “Sosie” [so-zee] is French for twin or doppelganger, and as it says right on the bottle, “We are inspired by the wines of France. So we employ an Old World approach to wine growing that favors restraint over ripeness, finesse over flamboyance. Our aim is to craft wines that show a kinship with France’s benchmark regions. Wines that are their sosie.” those bottles and the crossed-keys of the papal crest. It was a symbol you could trust, my mom used to say. I never forgot that, and as a young adult one of the first places I had to visit in France was Chateauneuf. To this day I still love those wines.”

those bottles and the crossed-keys of the papal crest. It was a symbol you could trust, my mom used to say. I never forgot that, and as a young adult one of the first places I had to visit in France was Chateauneuf. To this day I still love those wines.”

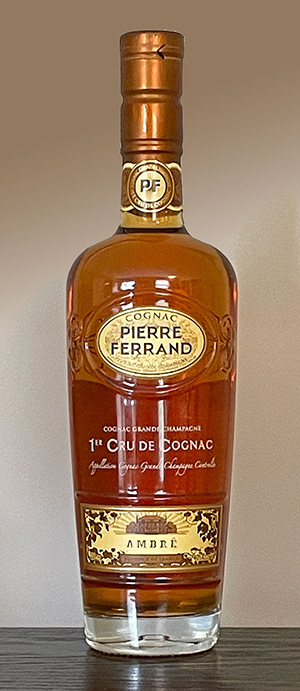

First, let’s talk about brandy vs. Cognac. Brandy is a liquor distilled from grape wine and aged in wood. (Brandy can be made from fruits other than grapes as well, but that’s a story for another time.) Cognac is brandy that specifically comes from the town of Cognac and the delimited surrounding areas in western France. (The one which has the most favorable soil and geographical conditions is Grande Champagne.) So, all Cognacs are brandy, but not all brandies are Cognac. For more detail on Cognac, click

First, let’s talk about brandy vs. Cognac. Brandy is a liquor distilled from grape wine and aged in wood. (Brandy can be made from fruits other than grapes as well, but that’s a story for another time.) Cognac is brandy that specifically comes from the town of Cognac and the delimited surrounding areas in western France. (The one which has the most favorable soil and geographical conditions is Grande Champagne.) So, all Cognacs are brandy, but not all brandies are Cognac. For more detail on Cognac, click