In the 1970s, Portugese rosés such as Lancers and Mateus were the height of sophistication to many young wine drinkers: “It’s imported, and comes in a fun bottle!” With age comes wisdom, and these wines were eventually abandoned for the justifiably famous fortified wines of Portugal, Port and Madeira, produced by many ancient and famous houses.

In the 1970s, Portugese rosés such as Lancers and Mateus were the height of sophistication to many young wine drinkers: “It’s imported, and comes in a fun bottle!” With age comes wisdom, and these wines were eventually abandoned for the justifiably famous fortified wines of Portugal, Port and Madeira, produced by many ancient and famous houses.

Much less well-known is Portugal’s status as a producer of both red and white table wine, ranking in the world’s top ten in production. With a population of just 10 million, but top five in per capita consumption, much of that wine is sipped by the thirsty Portuguese.

The Quinta [Estate] of Vesúvio has a long and storied history. António Bernardo Ferreira bought the property in 1823, at that time called Quinta das Figueiras. The property was mostly covered with wild scrub stretching up the mountainside and an abundance of fig trees, which gave it its name. He felt that this property had enormous potential as vineyards. It took his team of five hundred workers thirteen years to carve terraces out of the steep slopes and plant thousands of vines. Within the boundaries there are seven hills and thirty-one valleys. On the summit of each hill stands a ruined old lookout post, which once guarded the property. The tallest lookout is called the Raio de Luz, The Ray of Light. From there you can survey the full 360º aspect of the vineyards.

Vesúvio is situated far upriver in the Douro Superior, 75 miles (120 kilometers) from Portugal’s Atlantic coast and only 28 miles (45 kilometers) from the border with Spain. Vesúvio has a total area of 806 acres (326 hectares), of which 329 acres (133 hectares) are planted with vines. The rest, almost two-thirds, has been conserved in its natural state. Many other things grow at Vesúvio besides vines: oranges, lemons, figs, almonds, walnuts, grapefruits, pomegranates and many more exotic fruits and herbs.

Vesúvio also has great variations in altitude, from 426 feet (130 meters) at the riverside to 1,739 feet (530 meters) at the top of the tallest ridge. Being so far inland, the Quinta experiences climatic extremes, reaching very high temperatures in summer and very low ones in winter. It is extremely dry, with an average of only 16 inches (400mm) of rain falling each year.

In 1827, Ferreira built the winery, with its eight granite lagares (large, open vats or troughs), in which wine grapes are crushed by foot to this day, and eight chestnut vats, each capable of holding the equivalent of one lagar of Port. This original winery is where all of Vesúvio’s Port is still made. The facility was more than just a winery though; it was a whole community in its own right with orchards, gardens, and a village where the workers lived with their families. There was even a school, which would have been the nearest one for dozens of miles in any direction.

Quinta do Vesúvio

After working with the property for seven years, in 1830 Ferreria decided to rename the estate Quinta do Vezúvio (originally with a ‘z’ as was common in Portuguese spelling at that time). At the time, Ferreria boasted, “All the English have poured praise on my lodge and hold that they cannot find another adega [wine house] to match mine in the Douro … stating frankly that both in Oporto and the Douro, nobody has better wines.” In an unprecedented move, Ferreira exported his wines directly from his winery to the United Kingdom, then the largest market for Port by far. His aim was to persuade the authorities of the great quality of wines from the Douro Superior and hence the need to extend the Denominação de Origem Controlada. It had been established in 1756, almost 180 years before the French established their own similar quality system, but many Portugese winemaking regions were originally excluded.

During his life, Ferreira was involved with many of the most famous Quintas in the Douro Superior. Vesúvio, though, was his showpiece, and the only one mentioned In the memorial marking his death in 1835.

In 1834 Dona Antónia married Bernardo Ferreira II, Ferreira’s son, in the small chapel at her parents’ farm, the Quinta de Travassos. Following his death in 1844, she and their children inherited all of his vast Douro empire, but Antónia was adamant that Vesúvio should remain exclusively her own, and proceeded to extend the fame and reputation of the operation. She was the first to bottle her wines and sell them under the Quinta’s own name, unprecedented in the nineteenth century.

When phylloxera ravaged the Douro, Antónia began to experiment with new grape varieties and new techniques of grafting in her vineyards. Predictably, during these years the Portuguese wine economy suffered significantly. While other producers in the Douro were laying off their employees, Antónia found ways to keep them on, planting orchards, nut trees, cereals, and other crops, as well as grazing flocks of animals. In the 1870s and 1880s she also renovated and expanded the house and the chapel, which remain today just as she rebuilt them.

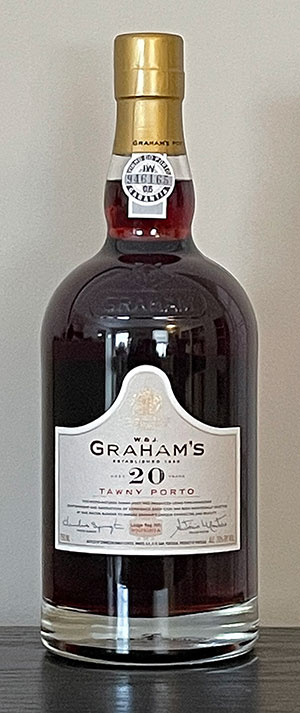

Following Dona Antónia’s death in 1896, Vesúvio was held by the Briti Cunha family for many generations until 1989, when the Symingtons, winemakers in the Douro for five generations, assumed possession. In 1882 the first Symington, Andrew James, moved from Scotland to Portugal to work for W & J Graham’s. But their ancestry in Port goes back even further. When Andrew James married Beatrice Leitão de Carvalhosa Atkinson, he married into a lineage that goes all the way back to Walter Maynard, who in 1652 was one of the very first British Port merchants to export wine from Oporto.

Symington Family Estates bills itself as the leading producer of premium-quality Ports in the world, with brands such as Graham’s, Cockburn’s, Dow’s, and Warre’s. SFE is also the leading vineyard owner in the Douro Valley with 2486 acres (1006 hectares) of vineyards across 27 quintas, all of which are managed according to sustainable viticulture standards; much of them are also organically farmed. When the Symingtons bought Quinta do Vesúvio, they decided that the sole objective would be to create outstanding vintage wines, initially focusing exclusively on Vintage Port and later adding dry (Douro DOC) wines, including this one.

Pombal do Vesúvio 2018 Douro

This is Vesúvio’s second-tier wine, a blend of 50% Touriga Franca, 45% Touriga Nacional, and 5% Tinta Amarela. It is named after the estate’s dovecote, a structure intended to house pigeons or doves, or “pombal” in Portugese, which is surrounded by vineyards. Unlike the first-tier fruit, the grapes are transported to the Quinta do Sol winery for processing and fermentation.

The wine is dark purple, with subtle aromas of roasted plum with a hint of thyme. The palate features quite tart red cherry and blackberry, the fruit rather recessive in the Old World style. It’s all supported by moderate black-tea tannins. 2,000 cases were produced, and the ABV is 14.5%.

Top of page: https://winervana.com/blog/

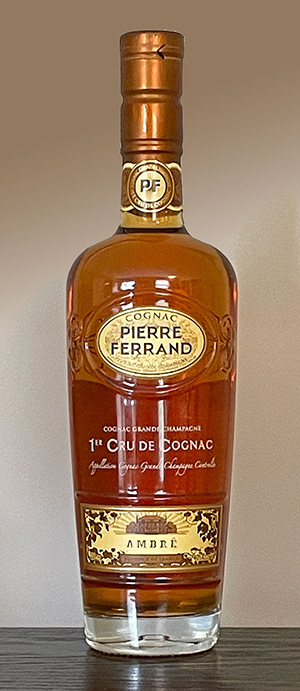

First, let’s talk about brandy vs. Cognac. Brandy is a liquor distilled from grape wine and aged in wood. (Brandy can be made from fruits other than grapes as well, but that’s a story for another time.) Cognac is brandy that specifically comes from the town of Cognac and the delimited surrounding areas in western France. (The one which has the most favorable soil and geographical conditions is Grande Champagne.) So, all Cognacs are brandy, but not all brandies are Cognac. For more detail on Cognac, click here.

First, let’s talk about brandy vs. Cognac. Brandy is a liquor distilled from grape wine and aged in wood. (Brandy can be made from fruits other than grapes as well, but that’s a story for another time.) Cognac is brandy that specifically comes from the town of Cognac and the delimited surrounding areas in western France. (The one which has the most favorable soil and geographical conditions is Grande Champagne.) So, all Cognacs are brandy, but not all brandies are Cognac. For more detail on Cognac, click here.

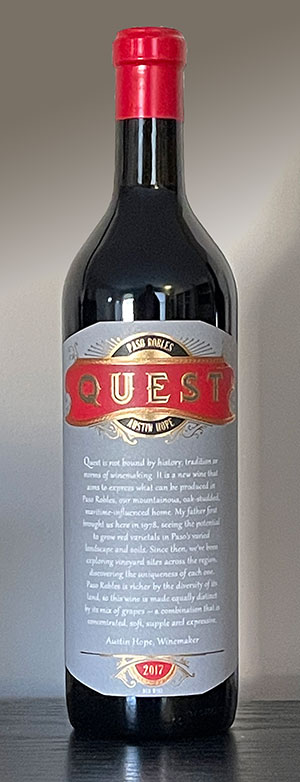

Chuck Hope and his wife Marilyn came to

Chuck Hope and his wife Marilyn came to

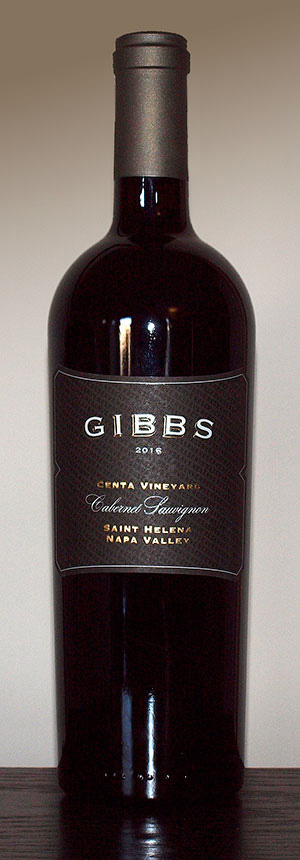

In 1947, Dr. Lewis Gibbs Carpenter Jr., a farmer and psychologist, moved to Saint Helena from Gilroy and bought land on the Napa Valley floor. He began to work the property by growing walnuts, dates, and a small selection of grapes in the 1950s. Over the next twenty years, he replaced most of the nut and fruit orchards with several Bordeaux varietals of grapes, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Sauvignon Blanc, and Merlot, all of which were beginning to gain international attention following the

In 1947, Dr. Lewis Gibbs Carpenter Jr., a farmer and psychologist, moved to Saint Helena from Gilroy and bought land on the Napa Valley floor. He began to work the property by growing walnuts, dates, and a small selection of grapes in the 1950s. Over the next twenty years, he replaced most of the nut and fruit orchards with several Bordeaux varietals of grapes, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Sauvignon Blanc, and Merlot, all of which were beginning to gain international attention following the  Dr. Lewis Gibbs Carpenter Jr.

Dr. Lewis Gibbs Carpenter Jr. Craig Handly

Craig Handly Spencer Handly

Spencer Handly

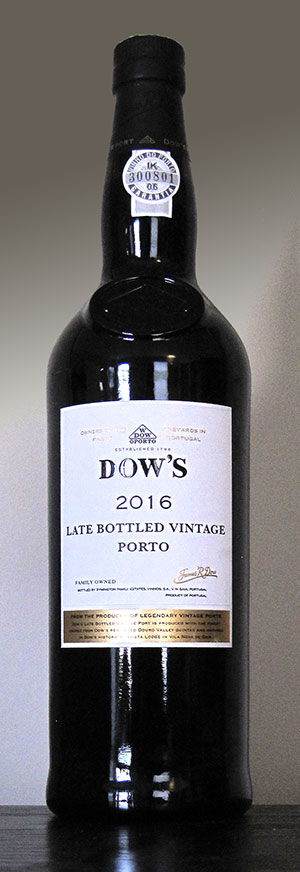

True Ports hail from the

True Ports hail from the

Long before California became America’s leading winemaking state, plenty of wine was being made in New York. The Hugeunots, a French Protestant sect of the 16th and 17th centuries, planted grapevines there in the 1600s. The first commercial plantings of native American grape varieties began in 1862. Shortly thereafter, the area established a reputation for making sweet sparkling wines, and by the end of the 19th century plantings had increased to around 25,000 acres.

Long before California became America’s leading winemaking state, plenty of wine was being made in New York. The Hugeunots, a French Protestant sect of the 16th and 17th centuries, planted grapevines there in the 1600s. The first commercial plantings of native American grape varieties began in 1862. Shortly thereafter, the area established a reputation for making sweet sparkling wines, and by the end of the 19th century plantings had increased to around 25,000 acres.

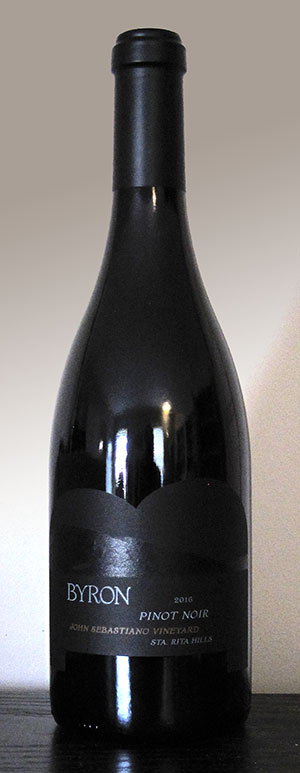

The Sta. Rita Hills

The Sta. Rita Hills  True Ports hail from the

True Ports hail from the

As a reviewer and source of reliable information, I am supposed to be as objective and unbiased as possible. But not today. Keenan wines have long been some of my favorites. If you need impartiality, please come back soon. If not, read on.

As a reviewer and source of reliable information, I am supposed to be as objective and unbiased as possible. But not today. Keenan wines have long been some of my favorites. If you need impartiality, please come back soon. If not, read on.

In the 1970s, Portugese rosés such as Lancers and Mateus were the height of sophistication to many young wine drinkers: “It’s imported, and comes in a fun bottle!” With age comes wisdom, and these wines were eventually abandoned for the justifiably famous fortified wines of Portugal, Port and Madeira, produced by many ancient and famous houses.

In the 1970s, Portugese rosés such as Lancers and Mateus were the height of sophistication to many young wine drinkers: “It’s imported, and comes in a fun bottle!” With age comes wisdom, and these wines were eventually abandoned for the justifiably famous fortified wines of Portugal, Port and Madeira, produced by many ancient and famous houses.